28

Elbow, Wrist, and Hand Tendinopathies

General Anatomy

Tendons are viscoelastic structures with unique mechanical properties. They are composed of connective tissues made of collagen, tenocytes, and ground substance, and they are poorly vascularized. Tendons allow muscle to transmit forces that create motion.1

The strength of a muscle depends on its cross-sectional area. A larger cross-sectional area provides greater contraction force with transmission of greater tensile loads through the tendon. Tendons with a larger cross-sectional area also are able to bear higher loads.2

The factors that most affect tendons’ biomechanical properties are aging, pregnancy, mobilization (or immobilization), and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Up to the age of 20, the collagen cross-links in tendons increase in number and improve in quality, which equates with increased tensile strength. With aging, tensile strength decreases.2

General Pathology

Tendinitis is defined as an acute inflammatory response to injury of a tendon that produces the classical signs of heat, swelling, and pain.3 Physicians and therapists historically have treated tendinitis as a phenomenon of tendon inflammation. However, recent, compelling histologic evidence has resulted in a change of terminology. The term angiofibroblastic hyperplasia or angiofibroblastic tendinosis (hereafter referred to as tendinosis) describes the pathologic alterations seen in the tissue of clients diagnosed as having tendonitis. A visible change occurs in the gross appearance of the tissue. Microscopically, normal tendon fibers are arranged in an orderly fashion. With tendinosis, the tendon fibers are invaded by fibroblasts and atypical vascular granulation tissue, and the adjacent tissue becomes degenerative, hypercellular, and microfragmented. Typically, only a few, if any, inflammatory cells are seen histologically. Tendinosis now is thought to be a degenerative pathologic condition, not an inflammatory one. Experts currently believe that true tendinitis is rare and that the condition hand therapists see in clients is tendinosis.

This histologic evidence has some intriguing implications for therapists: 1) we should question traditional approaches to the treatment of tendonitis as an inflammatory condition, and 2) we should alter our hand therapy treatments to fit the evidence of a tendinosis pathology.4

Individuals most likely to have tendinosis 1) are over age 35; 2) engage in a high-intensity occupational or sports activity three or more times a week for at least 30 minutes per session; 3) use a demanding technique for the activity; and 4) have an inadequate level of physical fitness. Symptoms occur when the tissue is worked beyond its tolerance (i.e., overused).1

General Treatment Suggestions

Progression of Treatment

As hand therapists, we are taught to believe that we should perform passive stretching of the involved structures. However, this poses a dilemma, because passive stretching can injure tissue. Clients find it difficult to truly relax for passive self-stretching, partly because of an appropriate anticipation of pain. Some experts have found that clients recover full passive stretching capability when pain-free, upgraded exercises are used instead of therapist-assisted passive stretching. This point deserves further research. In the meantime, if you perform passive stretching of involved structures, be very careful to avoid pain and monitor the client’s pain after the stretching session. (See Chapter 4 for more information on tissue-specific exercises.)

Precaution. Always avoid pain with exercise; pain is a sign of injury.

Lateral Epicondylosis (Tennis Elbow)

Anatomy

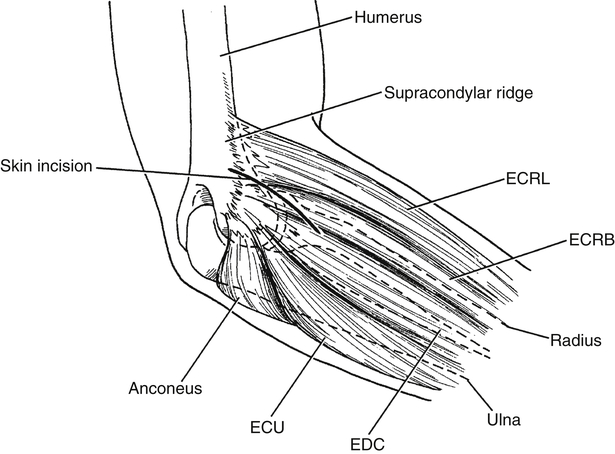

The lateral epicondyle of the humerus is the origin of the symptomatic muscle-tendon units in lateral epicondylitis, commonly known as tennis elbow (Fig. 28-1). The extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) is most often involved, followed by the extensor digitorum communis (EDC).

Diagnosis and Pathology

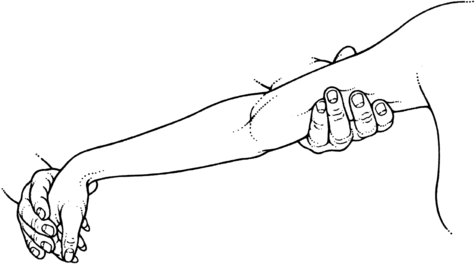

Clients usually have point tenderness at the lateral epicondyle, possibly anterior or distal to it. Point tenderness at the supracondylar ridge may indicate involvement of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL). Clients with lateral epicondylitis complain of nighttime aching and morning stiffness of the elbow. Gripping provokes pain, as does resisted wrist extension, supination, digital extension, and wrist radial deviation. Grip strength is reduced when the elbow is extended, and pain may be worse with this position (e.g., when carrying a briefcase). Tightness of the extrinsic extensors is common, and stretching of these muscles causes pain (Fig. 28-2).

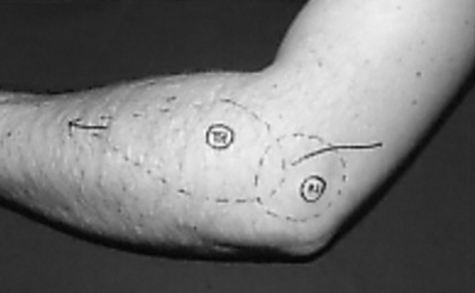

The test for tennis elbow is called Cozen’s test (Fig. 28-3). The examiner’s thumb stabilizes the client’s elbow at the lateral epicondyle. With the forearm pronated, the client makes a fist and then actively extends and radially deviates the wrist with the examiner resisting the motion. Severe, sudden pain in the area of the lateral epicondyle is a positive test result.5

Mill’s tennis elbow test originally was described as a manipulation maneuver, but it can be used as a clinical test. The client’s shoulder is in neutral. The examiner palpates the most tender area at or near the lateral epicondyle, then pronates the forearm and fully flexes the wrist while moving the elbow from flexion to extension. Pain at the lateral epicondyle is a positive test result. (For more information on this topic and other provocative tests, see Fedorczyk’s work.)1,5

Radial tunnel syndrome differs from lateral epicondylitis in that the pain is more diffuse and occurs within the muscle mass of the extensor wad rather than at the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 28-4). The middle finger test can be used to detect radial tunnel syndrome (Fig. 28-5). Another test for this syndrome is to tap (percuss) over the superficial radial nerve in a distal to proximal direction. The test result is positive if paresthesias are elicited.5

Nonoperative Treatment

Precaution. Do not use heat if the injury site is inflamed or swollen.

Ice also may be used for pain relief. The vasoconstrictive effect of ice may help normalize the neovascularization associated with the condition.6 Continuous-wave ultrasound and high-voltage pulse current (HVPC) have been reported to reduce pain.1 Although friction massage has been recommended for healing and pain relief, many clients find this technique too painful to tolerate. Fedorczyk1 notes that more research is needed on the use of soft tissue mobilization to treat tendinosis.

Precaution. Eccentric exercises should be performed with caution because they are more forceful.

Eccentric exercise helps restore tissue tolerance of the eccentric loads associated with sports and other functional activities. Eccentric exercise is believed to stimulate collagen production, which is considered the key to recovery from tendinosis. However, favorable responses of eccentric exercise for tennis elbow have not been supported by research to date.1