Elbow Plica

Erich Gauger

Julie E. Adams

INTRODUCTION

A plica is a synovial fold that is postulated to be a remnant of the embryonic septum. Plicae have been described in multiple joints and can cause clinical symptoms, particularly when the structures become thickened or inflamed (1,2,3,4 and 5). Plicae of the elbow were first described as “humeral radialis labrum” by Testut in 1912 (6), with Trethowan (7) and Ogilvie (8) defining the plicae as a synovial band crossing the junction of the capitellum and radial head. Plicae of the elbow have been termed the synovial fold of the humeroradial joint (9), lateral synovial fringe (10), circumferential synovial fold (11), snapping plicae (4), meniscus-like structure (12), and synovial fold (12). The increased awareness of plicae as a source of clinical pathology can be attributed to the advent and increased utilization of elbow arthroscopy. Despite this awareness, plica remains an elusive diagnosis and requires a high degree of clinical suspicion given the oftentimes vague posterolateral elbow pain with which patients often present.

DEVELOPMENT AND ANATOMY

The elbow joint is composed of three separate articular surfaces that form from mesenchymal cavitation in a specific sequence. First, the radiohumeral joint forms, then the ulnohumeral joint develops, and finally the radioulnar joint forms, leading to a confluence of these cavities (13). Plicae are therefore hypothesized to be the septal remnants of this process with the presence of plicae an expected part of normal physiology. Duparc et al. (9) and Isogai et al. (12) have provided substantial insight into the anatomy and histology of plicae. Isogai et al. (12) studied the macroscopic anatomy and histology of 179 cadavers and 40 embryos and found that all specimens had a synovial fold providing further evidence that plicae are normal remnants of embryologic development. They identified three basic macroscopic patterns classified on the shape and texture of the fold: villous, fringed, and plicate. More importantly, the authors found that all specimens had a synovial fold anchored at the anterior and posterior margins of the radial notch that extended a variable distance laterally

toward the annular ligament. Anterior folds continued as a thin layer of synovial tissue to the tip of the coronoid process and tended to be thinner than posterior folds, which also extended more laterally than did anterior folds.

toward the annular ligament. Anterior folds continued as a thin layer of synovial tissue to the tip of the coronoid process and tended to be thinner than posterior folds, which also extended more laterally than did anterior folds.

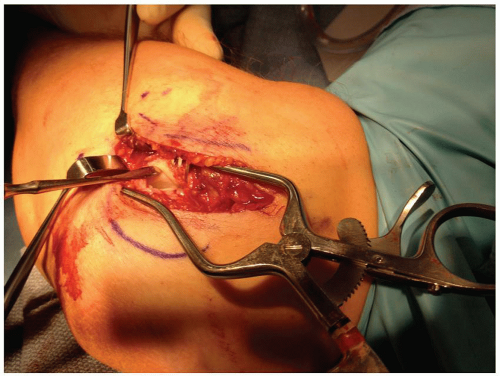

There were two other types of folds defined by the fact that neither of them reached the anterior or posterior margin of the synovial tissue around the ulna at the radial notch. A lateral fold was present in 38% of patients and was always separate from anterior and posterior folds. Typically, the lateral fold was located deep to an area correlating to the superficial attachment of the lateral collateral ligament on the annular ligament. Occasionally, if anterior and/or posterior folds were long enough, there would be overlap with the lateral fold. Complete circular fold was seen in four specimens and encompassed the entire synovial tissue surrounding the radial head from the anterior to posterior radial notch. This was essentially a fused anterior, posterior, and lateral fold. The authors conjectured that the lateral fold may result from repetitive compression of the annular ligament producing a fold in the lateral portion of the ligament. An important observation from the embryo dissection is the lack of lateral extension and the absence of lateral folds in embryos. Consequently, the lateral fold may be the culprit in symptomatic plicae (Fig. 18-1). Duparc et al. (9) supported many of the claims with respect to the histology and anatomy of adult elbows through their dissection of 50 adult elbows, although they did note that 14% of specimens did not have a synovial fold.

DIAGNOSIS

Plicae are a normal finding in 86% to 100% (9,12) of elbows, but only a small percentage of patients present with symptomatic plicae. It is thought that symptoms are related to the presence and pathologic changes in the lateral synovial fold. Patients may present with vague posterolateral elbow pain or a palpable or sense of “snapping” of the elbow with motion. Ruch et al. (14) hypothesized that repetitive microtrauma leads to thickening and fibrosis of the plicae with minor elbow instability potentially exacerbating inflammation and ultimately leading to snapping and pain.

The differential diagnosis for plica of the elbow includes radiocapitellar arthritis, osteochondral lesions, radial tunnel syndrome, lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, instability, and snapping triceps (over the medial epicondyle) (4,5,14,15 and 16). The latter three clinical entities closely mimic symptoms of plicae and are important to rule out. Likewise, in patients without overt snapping of the elbow with range of motion, a misdiagnosis of lateral epicondylitis is frequently made secondary to vague lateral discomfort and nondiagnostic clinical exam findings. Caputo et al. (17) found that plicae have an extensive nerve supply, and therefore, an inflamed plica under compression could be clinically mistaken for lateral epicondylitis. In fact, multiple authors have suggested plica excision as part of the treatment for lateral epicondylitis (18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree