Chapter 17 Eastern Systems of Soft Tissue Manipulation

Various forms of massage have been practiced in Eastern cultures for millennia. Indeed, some of the world’s oldest medical writings come from ancient Eastern cultures and describe various forms of soft tissue manipulation (massage) as an important medical healing art (see Chapter 1). Several of these systems are closely linked and have since been adapted by different cultures in many parts of the modern world. This chapter explores some of these systems and the interrelationships among them. Many of these systems are related to ancient Chinese culture, specifically to Taoism. This philosophy recognizes health as a state of balance or harmony within the individual and between the individual and nature. A state of ill health is seen primarily as an imbalance within the various internal and external forces that affect overall health. Intervention is therefore directed to restoration of the natural balance and harmony within the individual.

Traditional Chinese medical theory is grounded largely in the Taoist concept of yin—the positive, active male force—and yang—the negative, passive female force—in which ill health is seen as an excess or deficiency in the flow of the vital energy. Treatment is therefore aimed at rebalancing the system by using various methods (including acupuncture and acupressure) to restore the correct energy flow (Maciocia, 1989). A detailed and exhaustive treatment of each of these systems is well beyond the scope of this book. The intention here is simply to introduce the reader to a selected number of Eastern systems of massage and explore some of their interrelationships.

ACUPRESSURE

In classical acupuncture, stimulation is usually performed using several very fine but solid needles (acupuncture needles). Figure 17-1 illustrates an acupuncture treatment to the lower limb in a child with hemiplegia affecting the right side of the body. Multiple needles have been inserted at specific points along the lower limb. In addition, needles are also inserted into the upper limb and head of the patient (not shown).

As an alternative, stimulation can also be given using electricity, and this is known as electroacupuncture. Two basic techniques are used: electrical stimulation (from a specially designed unit) is applied directly to the needles that have already been inserted into the tissues; alternatively, electrical stimulation can be applied directly to each acupuncture point, using various surface electrodes. In this case, needles are not used and the skin is not penetrated. This technique can only be used safely with certain types of stimulation, such as high-voltage pulsed direct current (HVPDC). In the case of acupressure, stimulation is usually provided by direct digital pressure (finger or thumb), or with a handheld probe, to each appropriate acupuncture point.

There is a wealth of information on the topic of acupuncture, both on its place as a foundational concept in traditional Chinese medicine and regarding its emergence into contemporary health care (Filshie & White, 1997; Hopwood, 1997; Lewis, 1999; Linde et al., 2001; Sorgen, 1998; Vickers & Zollman, 1999). In fact, acupuncture is rapidly becoming an integral part of modern rehabilitation practice (Kerr et al., 2001) and a useful tool in primary care settings (Rega, 1999; Ross, 2001). The effect of acupuncture on various internal organ functions is another area in which there is a growing body of knowledge that in many, but not all, cases supports this ancient practice (Beal, 1999; Hu 2000; Takeuchi et al., 1999; Vickers, 1966; Vilholm et al., 1998; Wan 2000; Zhou et al.1999). However, acupuncture is not a treatment without some risk to the patient (Odsberg et al., 2001; White et al., 2001). Of particular concern is the possibility of introducing serious infection by the use of “dirty” needles. There has, therefore, always been an important need to sterilize the needles used in acupuncture treatments. With the advent of disposable needles, the risk of cross-contamination has been greatly reduced. Other adverse effects consist largely of unwanted reactions to the treatment.

The selection of acupuncture points for treatment within the scope of traditional Chinese medicine is usually made according to syndromes, whereas the Japanese-based Meridian Therapy School emphasizes the selection of points according to the channels involved. Other historical methods of selecting points for treatment include those determined according to point category, symptoms, seasons, and five elements. Modern acupuncture practice uses a combination of historical and contemporary methods to locate and select points for treatment (McDonald, 1999).

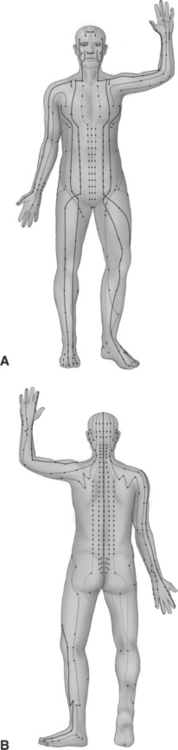

Acupuncture/acupressure points may be situated in an isolated location on the skin surface, or they may be found along a specific line of distribution—the so-called meridians. The meridians represent pathways (lines) on the body that run from various internal organ systems to the skin surface. Although the history of acupuncture and herbal medicine can be traced back to northern and southern China more than 4000 years ago, it was not until around 300 bc that the first text on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) appeared and the concept of acupuncture was fully described. This famous text was the Huangdi Nei Ching Su Wen (usually referred to as the Nei Ching) or The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. The text is said to have been written by Huang Ti (Huangdi), the Yellow Emperor himself, and in it, the meridians along which the life force, or energy, of the body (qi) flows and their acupuncture points are presented in diagrams. In total there are about 1000 acupuncture points, and in TCM, stimulating them is said to affect the flow of yin and yang (the opposing and complementary negative and positive energy sources) so that the body systems are maintained in proper balance (Beal, 1992). Figure 17-2 illustrates the location of some of the classical acupuncture points and the meridians associated with them.

The effects of acupuncture on pain have been studied for many years, both from a neurophysiological viewpoint and from its clinical application in both acute and chronic pain (David et al., 1998; Lao et al., 1999; Romoli et al., 2000; Vickers et al., 2004; Wedenberg et al., 2000). Of course, pain relief using hyperstimulation techniques can also be achieved through acupuncture and acupressure, as well as through techniques already presented such as trigger point stimulation, reflexology, point percussion therapy, and connective tissue massage. These techniques are effective because, histologically, the points and their immediate surrounding areas are associated with the same nerves, pressure, and stretch receptors (Weaver, 1985). Associated modalities—for example, cupping and the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)—can have similar effects (Anderson et al., 1974; Baldry, 1989; Fox & Melzack, 1976; Han, 1987; Lewit, 1979; Melzack, 1981, 1985; Travell & Simons, 1983, 1992).

Although it is beyond the scope of this book to provide detailed information concerning the neurophysiological basis of acupuncture and associated techniques in pain relief, there is abundant evidence of their effectiveness. The therapeutic effects of acupuncture, especially on pain, can be explained in part by the conventional understanding of neurophysiological concepts. The insertion of an acupuncture needle stimulates A delta nociceptor fibers, entering the spinal cord in the region of the dorsal horn. The A delta fibers are activated in response to the needle insertion/removal and to the twisting of the needles during the treatment. These fibers are rapidly adapting and responsible for the sharp, stabbing quality of pain. Activation of these fibers can produce a segmental inhibition of impulses traveling in the unmyelinated C fibers. Pain relief is also mediated by activation of the descending pain suppression mechanism and stimulation of endogenous opioid peptide release in the periaqueductal gray matter, spinal cord, and elsewhere. Various other substances, including serotonin, catecholamines, glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), may also mediate cardiovascular and analgesic effects. In addition, evidence that nitric oxide may play a role in mediating cardiovascular responses through the gracile nucleus–thalamic pathway has recently become available. Activation of these mechanisms helps to explain how the insertion of needles in one part of the body can have a long-lasting effect on pain felt elsewhere (He, 1987; Kerr et al., 1978; Sheng-Xing, 2004). These mechanisms also explain how acupressure and electroacupuncture can relieve pain.

Originally, acupuncture was one of a range of external therapies that included moxibustion (burning of the herb Artemisia vulgaris, a type of chrysanthemum) and traditional Chinese (amma) massage (Armstrong, 1972; Cheng, 1987). Before the invention of material capable of being honed fine enough to actually puncture the skin, pieces of stone and bone were used to press points on the skin. The response to stimulation of some points corresponds to that associated with the head’s zones mentioned previously in association with reflexology and connective tissue massage (see Chapters 11 and 16). It is widely accepted that some acupuncture points correspond to sites in specific head’s zones and some with trigger or motor points. At least 50% of acupuncture points are located directly over nerve trunks, the other half are within 0.5-cm of the trunks, and more than 70% coincide with trigger points (Chaitow, 1979, 1981; Melzack, 1981).

In modern rehabilitation practice, acupressure is growing rapidly in popularity (Romanchok, 1997), particularly as a technique that may be taught to the patient for self-treatment purposes. It is effective for relieving pain of musculoskeletal origin and for relieving muscle fatigue (Avakyan, 1990; Heinke, 1998; Hsieh et al., 2006; Li & Peng, 2000; Yip & Tse, 2006). Acupressure also appears to be effective for treating a number of problems in the area of women’s health and reproductive medicine (Beal, 1999; Hoo, 1997). Acupressure seems to be particularly effective for reducing the problems of nausea and vomiting in a wide variety of situations (Bowie, 1999; Chen et al., 2005: Cummings, 2001; Dibble et al., 2000; Harmon et al., 2000; Klein & Griffiths, 2004; Shenkman et al. 1999; Steele et al., 2001; Stern et al., 2001; Youngs, 2000). Acupressure can also promote relaxation, reduce anxiety, and encourage restful sleep (Agarwal, 2005; Chen et al., 1999; Tsay et al., 2005). In contrast, acupressure does not seem to promote weight loss (Ernst, 1997).

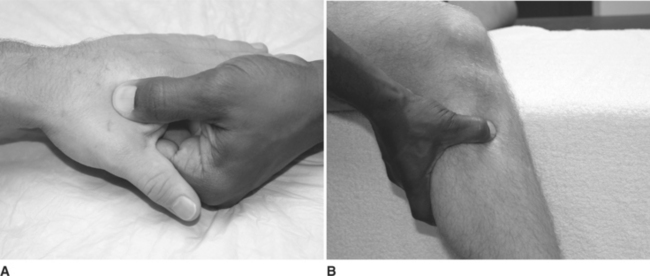

The many hundreds of acupuncture points can be divided into two main groups, those associated with pain relief and those concerned with the stimulation of various organ systems. In fact, both acupuncture and acupressure are good examples of treatment concepts that produce a remote site effect, largely mediated by an autonomic reflex (see Chapters 5, 11, and 16). Points are named by their meridians, which are linked to their sources in the internal organ systems. Two examples are the powerful acupuncture points used in anesthesia and in the treatment of pain: the large intestine (LI-) 4 and the stomach (St-) 36. LI-4 is found in the middle of the web space between the metacarpals of the thumb and index finger. In Chinese it is called Ho-Ku, which means “meeting valley.” The St-36 point is located slightly lateral and distal to the insertion of the patella tendon onto the tibial tuberosity (Figure 17-3).

Stimulation of the St-36 point is illustrated in Figure 17-3, B. The point lies slightly lateral and distal to the insertion of the patella tendon on the tibial tuberosity and, once again, is a location in which self-treatment is possible.

The classic method of locating each specific point is by the use of directions given in body inches (cun). Each person’s cun is slightly different in length and should be used to locate each point on the body. The length of the middle phalanx of the middle finger, or the distal phalanx of the thumb, can be used as the unit of length for the body inch, or cun. For the LI-4 point, the interphalangeal joint of the thumb is placed in the middle of the outstretched web of the other hand. By rolling up onto the tip of the thumb, the meeting valley point is found. It is hypersensitive and is readily detected by palpation and other methods.

Table 17-1 has been adapted from a number of the texts (Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1975; Chaitow, 1971; Tappan & Benjamin, 1998). It provides examples of useful points for a range of symptoms, injuries, and related problems that are common. A number of other points may be of use for the conditions and symptoms referred to in Table 17-1. Those interested in using acupressure as part of a comprehensive treatment plan should look for them in the texts listed in conjunction with this section. If acupressure techniques prove to be useful, it may be possible to teach the patient how to self-administer the treatment, thereby enabling the patient to manage his or her own problem when needed.

Table 17-1 Some Acupuncture Points, Their Positions, and Related Indications

| POINT | LOCATION | INDICATIONS |

|---|