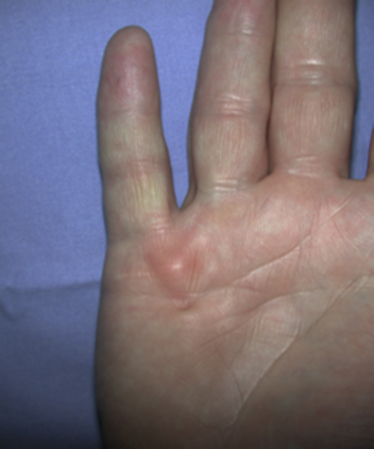

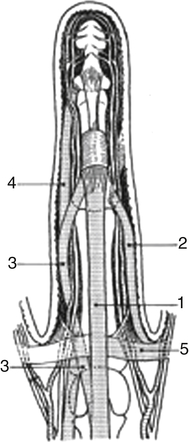

Dupuytren’s disease is eponymously attributed to Baron Guillaume Dupuytren, a French physician, who first described the condition in a December, 1831, lecture at the Hotel Dieu, as reported by his assistants.1 At the time of his report, Dupuytren was unaware that others had previously described the condition. The earliest identifiable report was by the Swiss physician, Felix Plater, in 1614. In 1777, Henry Cline from London described the condition and had demonstrated in cadavers that the palmar fascia alone was involved.2 The condition was briefly mentioned by Kline’s pupil, Astley Cooper in his 1822 “Treatise on Dislocations and Fractures of the Joints.”3 Nonetheless, in his “Lecons orales” published in 1832, Dupuytren’s description of the condition, the pathoanatomy, and treatment were presented in far greater detail than the previous reports.4 Since that time, although many surgeons and scientists have contributed to our understanding of the disease and its treatment, the precise etiology of the condition remains unknown. Although most commonly seen in older men of northern European descent, Dupuytren’s disease is seen globally across nearly all ethnic groups. In Caucasians, the global incidence is said to be 3% to 6% with the incidence increasing with advancing age.5 The disease appears to be inherited in 10% to 30% of cases with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of variable penetrance.6 Men usually present 10 years earlier with a peak incidence at age 45 to 50 and, compared to women, have higher prevalence of this disease, varying from 10:1 to 2:1 depending on the series reported.7,8 Age of onset is significant, because those patients with an early onset are more likely to experience a more severe clinical course. Dupuytren’s disease frequently appears as an isolated affliction of the fascia of the palm and digits. The thumb and index rays are much less often involved (5% to 7%) than the ulnar digits (50% to 60%).9 Studies report bilaterality existing between 42 to 98% of cases.10 In some patients, it occurs in conjunction with fibroproliferative involvement of the plantar fascia, termed Ledderhose disease, or the fibrous tissues of the tunica albuginea of the penis, termed Peyronie disease, or within the subcutaneum over the PIP joint, here termed knuckle pads. This constellation of fibroproliferative disorders is referred to as Dupuytren diathesis, a concept attributed to Hueston11 who recognized several predisposing or “at risk” factors, including a positive family history, bilaterality, and the lesions outside the hands mentioned earlier. Early age of onset has been previously mentioned. • Diabetes mellitus12: There is a well-established increased incidence of diabetes in patients with Dupuytren’s disease; although Dupuytren’s disease, when present, is typically more nodular and less cordlike. • Alcoholism13: Some studies have shown a positive correlation. • Trauma14: The role of trauma is also controversial. Some studies show a positive correlation. Dupuytren’s disease following trauma usually is non-progressive and may retrogress suggesting that this may be a different pathologic condition. • Epilepsy15: The incidence of Dupuytren’s disease in epileptic patients is notably high according to some studies. The role of phenobarbital, commonly prescribed for epilepsy, in the development of Dupuytren’s disease is controversial. In the hand, Dupuytren’s disease is characterized by the presence of two structures, nodules and cords.16 Nodules are comprised of hyper-cellular collagen bundles, whereas cords are less cellular. There is disagreement regarding whether these are distinct aspects of the disease or simply stages in the evolution. A controversy remains regarding whether normal fascia converts to Dupuytren’s disease or develops independently. It remains curious as to why some elements (such as, longitudinal fibers) become involved, while anatomically adjacent elements (such as, the transverse and vertical elements) do not. Nodules, along with skin pits and distortions of the distal palmar crease are often the first visible evidence of Dupuytren’s disease (Fig. 39-1). They typically appear near the distal palmar crease on the ulnar side of the hand and may be symptomatic with patients describing itching and burning, or they may be completely asymptomatic. They may appear and rapidly or slowly enlarge, or they may appear and remain stable for decades. At a later stage, cords may appear. Longitudinal cords, termed pretendinous cords, parallel the pretendinous bands and may insert in a fashion similar to the insertions of the normal longitudinal fascia, or they may continue on into the digit as a central cord, inserting into the proximal or middle phalanx (Fig. 39-2). Contracture of the pretendinous cord, under the influence of myofibroblasts, thus, may cause an isolated MP or a combined MP and PIP joint contracture, depending on the distal insertion of the cord. This pretendinous cord, continuing distally into the digit as a central cord, usually does not disturb the anatomical course of the neurovascular bundle (NVB), and its surgical dissection should be relatively easy and safe. Frequently, the pretendinous cord becomes contiguous with the diseased lateral digital fascia, now termed lateral digital cord, to then become what has been termed a spiral cord (Fig. 39-3). This pathoanatomic variant, because it causes a contracture of the MP joint, displaces the NVB centrally and superficially, placing it in harm’s way of the unskilled and unwary surgeon. In the finger, the pathoanatomy of Dupuytren’s disease is more complex than that of the palm, mirroring the more complex normal fascial anatomy of the digit (see Fig. 39-3). McFarlane17 identified four cords that may cause a contracture of the PIP joint including the following: The affected digit may assume a posture similar to a so-called “boutonnière” deformity with a flexed PIP joint and a hyperextended DIP joint (Fig. 39-4). Over time, the DIP joint’s volar plate becomes ineffective, the central slip of the extensor mechanism becomes elongated and ineffective, and the lateral bands across the middle phalanx become contracted. Simple excision of cords of Dupuytren’s disease will not be successful in restoring function to this digit. The span of the digits may be compromised as natatory cords appear and contract. Surgery continues to be the gold-standard treatment for progressive Dupuytren’s contractures. Typically, intervention is recommended in patients with MP joint contractures of at least 30° and/or any PIP joint contractures with associated functional impairment.9 A variety of surgical interventions exist and are largely classified by the amount of diseased tissue removed. The least invasive of surgical interventions, percutaneous needle aponeurotomy/fasciotomy may be considered little more than a modification of the original technique performed by Sir Astley Cooper and later known as the Cooper fasciotomy.18 This technique, modified and later revived by the French rheumatologists, Lermusiaux and Debeyre,19 is ideal for elderly individuals with multiple comorbidities, because it allows for a rapid increase in finger extension with minimal recovery time and can be safely performed under local anesthetic alone. The technique has grown in popularity since its reintroduction, and a number of excellent publications document its initial efficacy and safety when performed by experienced practitioners. The durability in terms of time to recurrence seems to be the major criticism of the technique. Nevertheless, it has become part of many hand surgeons’ armamentarium to treat contractures of both MP and PIP joints. As typically described, the surgeon uses a fine-tipped hypodermic needle, stabbed through the skin at multiple locations overlying the contracting cord to make a series of micro-lacerations. The cord, thus weakened, eventually ruptures and the contracted joint extends to various degrees. Multiple involved fingers can be treated at the same operative procedure. The more widely-used procedure to treat Dupuytren contractures is regional (subtotal or limited) fasciectomy, which remains today the accepted gold-standard for primary contracture release. This procedure involves generous skin incisions (Fig. 39-5) and careful dissection and excision of just the involved diseased fascia. This is different from radical fasciectomy advocated by McIndoe and Beare,20 who recommended extensive removal of involved and noninvolved palmar and digital fascia. This treatment has fallen out of favor due to its higher complication rates without convincing evidence of a lower rate of recurrence. There exist many variations of so-called limited, as opposed to radical, fasciectomy. They differ primarily in the extent of exposure (that is, dissection and removal of the contracting fascia). For example, rather than removing all involved fascia, the surgeon may choose to excise only a short segment at a location determined to result in maximum extension of the contracted joint. This has been termed segmental fasciectomy,21 to distinguish this procedure from open fasciotomy. The incisions are either sutured directly or closed by advancement or rotation/transposition (Z-plasty) flaps, the wounds are covered with skin grafts, or the wound is simply left open to heal by secondary intention (McCash technique22). These are not mutually exclusive techniques, and often all three maneuvers may be employed in the same hand. It is yet to be established that one fasciectomy technique yields notably improved results over another. All are associated with a low but consistent incidence of complications, including hematoma formation, nerve and vessel injury, delay in healing, joint stiffness, particularly loss of PIP joint flexion, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). The surgical treatment of post-surgical recurrent contractures is even more complicated, because the skin is now scarred and the internal anatomy disturbed. The surgeon frequently must modify the technique to avoid disastrous complications, such as digital necrosis. One modification that addresses severely contracted PIP recurrences involves the initial application of gradual soft-tissue distraction devices, such as the Digit Widget, to straighten severely contracted PIP joints (Fig. 39-6). The device is attached to the skeleton of the middle phalanx, and a clever force-couple mechanism powered by rubber bands and monitored by the hand therapist gradually elongates contracted PIP joint capsule, volar plate, and collateral ligaments. At an obligatory second surgery, the scarred skin and pathologic fascia is removed and a full-thickness skin graft inserted.

Dupuytren’s Disease

History

Epidemiology

Presentation

Pathoanatomy and Evolution

Disease in the Palm

1, Central cord; 2, lateral digital cord; 3, spiral cord; 4, retrovascular cord; 5, natatory cord. (Redrawn from Leclercq C: The management of Dupuytren disease. In Mathes SJ, Hentz VR, editors: Plastic surgery, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.)

Other Digital Pathology Associated with Dupuytren’s Disease—Pseudo-Boutonnière

Operative Treatment

Percutaneous Needle Aponeurotomy

Fasciectomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dupuytren’s Disease