Chapter 46 Double-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has largely been a successful surgery over the last several decades, with satisfactory subjective patient outcomes in the short term.5 However, more recent long-term studies have found significant sequelae of ACL injury and its reconstruction with the development of early arthritic changes in a large percentage of patients. Pinczewski and colleagues19 have reported arthritic changes in 39% of patients who underwent patellar tendon autograft ACL reconstruction at 10 years postoperatively. Additionally, others have reported a subset of patients, between 30% and 40%, who have persistent instability or are unable to return to their previous level of activity.2 Although these results compare favorably with the nonoperative treatment of ACL injuries, potential areas for improvement obviously remain.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

The anatomy of the ACL has been studied for many years, with the assumption that a better understanding of the anatomy would lead to a better reconstructive procedure. In general terms, the ACL originates on the medial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle and runs obliquely to its insertion at the medial tibial eminence. It is narrowest in the midsubstance, with an average cross-sectional area of 36 mm2 in females and 44 mm2 in males.1 It then fans out to a broad insertion at both ends.18 The length of the ACL is depends on which fibers are measured; it can range from 22 to 41 mm.17

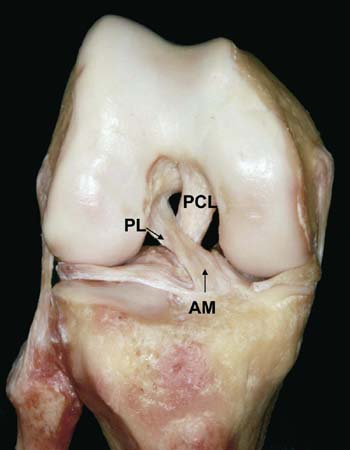

It is widely accepted that the ACL is composed of two functional bundles. This was first described in the 1930s and has since been confirmed by others.27 These two bundles, anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL), are named for their tibial insertion and have distinct functional properties (Fig. 46-1). Recent literature has shown that in response to an anteriorly directed tibial load, the in situ force in the PL bundle is highest at full extension and decreases with flexion, whereas the AM bundle is lower in full extension and increases to maximum at 60 degrees of flexion.7 Additionally, the PL bundle also resists anterior translation when the knee is subjected to a combined rotatory load (simulated pivot shift) when near full extension.18

Although researchers continue to investigate the anatomy and function of the ligament itself, others have revisited the insertional anatomy of the ACL. The last several years have provided a much greater detailed understanding of both the femoral and tibial insertions. On the femoral side, the overall shape is that of a segment of circle, with its anterior border straight and its posterior border convex. Ferretti and associates4 have studied the area of the femoral insertion site and found it to average 196.8 mm2. Individually, the AM bundle averaged 120 mm2 and the PL bundle averaged 76.8 mm2; however, there may be some ethnic variation. To help identify each bundle, there are distinct bony landmarks that signify the anatomic extents of each bundle as well as the ACL as a whole. The lateral intercondylar ridge (resident’s ridge) is the anterior border of the ACL. This bony landmark runs from proximal to distal with the knee straight, and no cruciate fibers insert anterior to this point. The lateral bifurcate ridge, which is subtle but often present, separates the anterior portion of the AM bundle from the PL bundle. Of importance is the understanding that these two insertion sites are vertical with the knee extended and horizontal with the knee in flexion. Therefore, the two bundles are parallel with the knee in extension but crossed with flexion.10 This explains the biomechanical features of the two bundles and aides in reconstruction.

On the tibial side, the insertion varies in shape in size.13,24 Medially, the ACL inserts up to a bony ridge that is an anterior extension of the medial intercondylar tubercle.22 Posteriorly, no fibers extend beyond a ridge of bone at the anterior aspect of the tibial spine between the medial and lateral tibial intercondylar tubercles. The portion of the ACL, the PL bundle, lies just anterior to the insertion of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus. The anterior and lateral borders are less well defined and consist of diffuse expansions. Similarly, there is no bony landmark that separates the two bundles on the tibial side.

Preoperative Considerations

Imaging

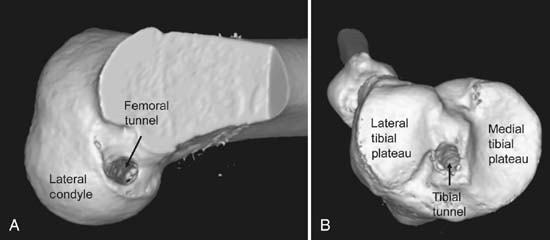

Plain radiographs are first obtained and consist of weight-bearing extension and 45-degree flexion posteroanterior views. Non–weight-bearing 45-degree lateral and axial (Merchant) views are also obtained. Standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences are helpful for diagnosing the ACL tear as well as any additional injuries. Oblique coronal views, taken in the plane of the ACL, are helpful for visualizing the two bundles of the ACL (Fig. 46-2). For cases involving revision ACL reconstruction, computed tomography (CT) with three-dimensional reconstructions provide better bone detail than MRI and are used to evaluate prior tunnel placement and the degree of bone lysis (Fig. 46-3).

Technique

Graft Selection and Preparation

Both autograft and allograft options exist for the double-bundle reconstruction and one must consider the patient’s age, anatomy, prior surgical history, activities, and occupation when discussing this with the patient. Although allograft tissue eliminates donor site morbidity, one must counsel the patient regarding possible disease transmission and potentially higher failure rate.24 If allograft is chosen, tibialis anterior tendons are preferable because of the large diameter and length. Two grafts are chosen, each at least 24 cm in length. After the graft diameters are determined (see later), each graft is trimmed so that its doubled-over diameter will be the desired size. Each end is stitched with a strong nonabsorbable suture to facilitate graft passage and fixation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree