Dorsal Block Pinning of Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Fracture-Dislocations

Elizabeth King

Mark Goleski

Jeffrey Lawton

DEFINITION

The laymen’s term “jammed finger” often is used to indicate an injury sustained to the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. If the injury occurs with sufficient force, the joint may suffer a fracture-dislocation, which can be a challenging injury to treat.

PIP fracture-dislocations, with a dorsal displacement of the middle phalanx are caused by disruption of the volar fibrocartilaginous plate, fragmentation of the middle phalanx where it attaches to this plate, and damage to the collateral ligaments on each side of the joint. Instability with dorsal displacement of the middle phalanx may result, accentuated by the unbalanced pull of the central slip.

Stiffness, pain, persistent subluxation, degenerative arthritis, and long-term dysfunction are common sequelae, even with appropriate treatment in the best of circumstances.

Dynamic external skeletal traction, extension block splinting or pinning, transarticular pinning, open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF), and volar plate arthroplasty are the techniques most commonly used to treat these injuries.

None of these techniques have proven to be satisfactory for all patients in all instances.

Extension block pinning has been used with reasonable success to stabilize unstable PIP fracture-dislocations. The use of this technique is predicated upon first obtaining the reduction and then allowing the extension block pin to maintain the reduction.

A retrograde K-wire is placed into the head of the proximal phalanx, mechanically blocking full extension of the joint and thereby preventing dorsal subluxation of the middle phalanx.

The advantages of this technique include its simplicity and the early mobility it affords an injured joint. It can be used alone or in combination with volar plate arthroplasty or ORIF.

ANATOMY

The PIP joint acts primarily as a hinge joint in the sagittal plane, although it does possess a few additional degrees of motion in the coronal and axial planes.17 It has an average range of flexion-extension of 105 degrees.16

The joint has a great deal of stability throughout its range of motion (ROM).16

When healthy, the joint is most stable in full extension.

A tongue-and-groove structure, formed by the bicondylar head of the proximal phalanx and the reciprocal concave surfaces of the middle phalanx, contours closely in this position.16

In the pathologic setting of a dorsal fracture-dislocation, some flexion confers PIP stability. As the joint flexes, the ligamentous elements lying volarly to the axis of rotation are primarily responsible for maintaining stability.16

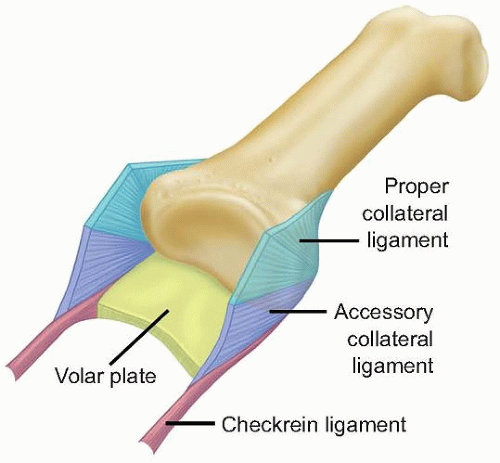

The volar plate, a structure that is ligamentous at its origin on the proximal phalanx and cartilaginous at its insertion on the middle phalanx, and the two collateral ligaments, one on the radial and one on the ulnar side of the joint, are the most important structures for stability (FIG 1).

Two out of three of these structures must be impaired for displacement of the middle phalanx to occur.

PATHOGENESIS

Although the PIP joint may become dislocated in any direction, dorsal displacement of the middle phalanx is the most common.

Simultaneous hyperextension and axial compression forces— such as those seen when a ball strikes the tip of the finger— stress the volar plate and the collateral ligaments.

Type I injury

If the force of injury is mild, it will result in only partial disruption of the collateral ligaments and the volar plate at its distal insertion on the middle phalanx.

The articular surfaces remain intact and the joint is stable.

If appropriate treatment is initiated promptly, an excellent long-term result is anticipated.13

Type II injury

If the force of injury is more substantial, bilateral longitudinal splitting of the collateral ligaments may occur in addition to rupture of the volar plate. Complete dorsal displacement of the middle phalanx is then possible due to the unopposed pull of the central slip.

The joint can be readily reduced and usually is stable following reduction.

Type III injury—stable

Type III injury—unstable

If the fracture at the base of the middle phalanx involves greater than 40% to 50% of the articular surface, collateral ligament support is lost. The joint exhibits persistent dorsal subluxation of the middle phalanx due to unopposed pull of the extensor tendon and lack of volar restraints.

Closed reduction, although often possible, cannot be maintained often leading to unsatisfactory overall results.19

A cadaveric biomechanical study of PIP joint fracture-dislocations reported that joints with simulated bony articular defects of the middle phalanx of 20% were stable through digit ROM. Simulated volar articular defects greater than 40% led to greater than 1 mm of dorsal subluxation.21

NATURAL HISTORY

The outcome following even a minor injury is often less satisfactory than the patient anticipates (ie, not “back to normal” in terms of appearance, ROM, and comfort). Although it is possible for a PIP joint that has suffered a fracture-dislocation to regain excellent function, persistence of a slightly stiff joint with a cosmetically thickened outline is common.

Delay in treatment or lack of vigilant care negatively affects outcome.10

Prolonged immobilization of the joint following reduction leads to stiffness. Early mobilization can avoid stiffness and may benefit the damaged articular cartilage.18

Patients should be reassured, however, that carefully planned treatment and compliance with the postoperative therapy regimen leads to long-term satisfactory results in most cases.10

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The history should elicit the mechanism of injury, nature of any medical treatment or manipulation of the digit before the current visit, and time elapsed since the injury.

The likelihood of a favorable result diminishes with increased time from injury, particularly beyond 6 weeks.9

The digit will look surprisingly normal at presentation in many cases, particularly if it has already been reduced.

The neurovascular status should be documented on examination before performing digital anesthetic block and reduction.

With the forearm supinated and the hand relaxed, observe the position of the patient’s fingers. Note the axial and rotational alignment of the digit.

Observe the patient’s fingers directly and fluoroscopically as he or she attempts to move them through a normal ROM. Dorsal subluxation often can be detected visually and through palpation.

Digital or wrist block anesthesia can be used to relieve discomfort associated with motion (FIG 2B).

If the joint can be moved through a full arc of motion without subluxation, adequate joint stability remains, and only brief immobilization will be required.

If redisplacement occurs, significant instability will result. The position of redisplacement is a clue both to the specific site of ligament injury and the optimal position for joint immobilization.8 Loss of active extension implies central slip injury.

For grossly stable digits, manipulate the joint passively through the normal ROM. Gentle lateral and dorsovolar shearing stresses are applied at full extension and at 30 degrees of flexion. The findings are compared to those of the contralateral uninjured digit (FIG 2C).

The position of the PIP joint at the point of instability suggests which of the soft tissue supports has been injured. Instability at more than 70 degrees of flexion indicates damage to the collateral ligaments. Instability in extension indicates disruption of both the collateral ligaments and the volar plate. The degree of joint laxity suggests the extent of injury to the ligaments, from microscopic tearing to complete rupture.

Palpate the PIP joint from all sides to determine point tenderness. Point tenderness often is valuable in localizing the injured structure.

Absence of point tenderness on the condyles may rule out significant injury to these structures. If the volar lip of the middle phalanx has been fractured, minor tenderness over the dorsum of the middle phalanx and greater tenderness volarly and laterally will be present.5

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Obtain anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs of the injured digit. Assess the digit for joint dislocation, subluxation, and fracture.

Evaluate the radiographs before performing the physical examination to detect potentially unstable fractures or dislocations before they are manipulated.

Radiographs of the hand as a whole (eg, the “fanned four-finger lateral” view) are not adequate. Subtle fracture-dislocations may be missed due to poor depiction of the areas of suspected pathology.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree