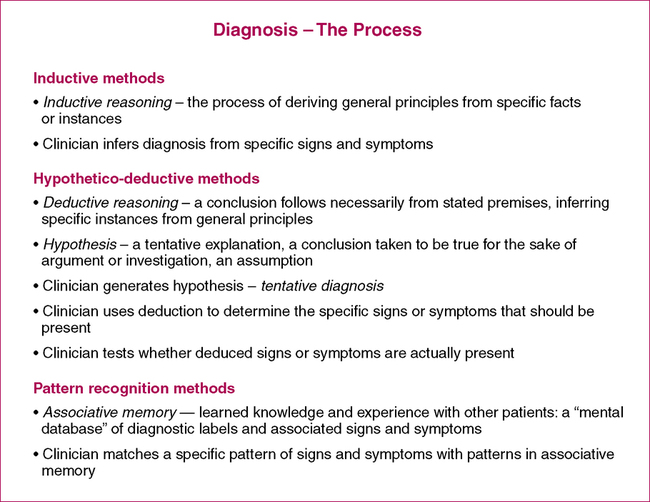

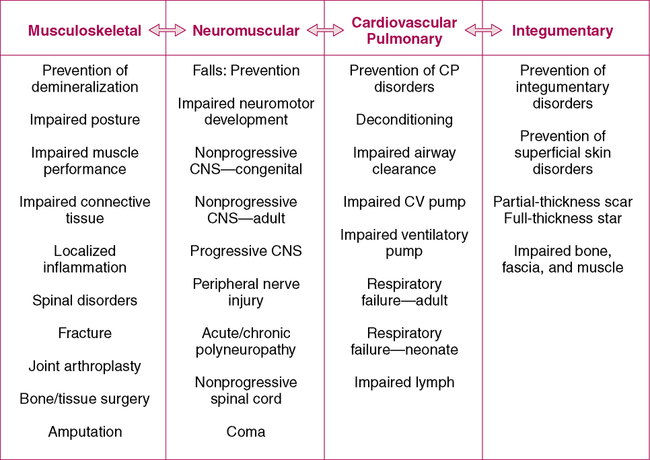

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe the role of physical therapists in establishing and documenting a diagnosis. 2. Describe the characteristics of the Assessment section of an evaluation report. 3. Appropriately document an Assessment for different case scenarios. The term diagnosis refers to a process that all PTs engage in: the act of evaluating the physical and subjective findings to make a decision about whether physical therapy will be helpful to a patient and, if so, what kind of therapy the patient should receive. The diagnostic process involves making a clinical judgment based on information obtained from history, signs, symptoms, examination, and tests that the therapist performs or requests. Different methods of diagnosis have been advocated; a few are discussed briefly in Figure 9-1 (also see References). The American Physical Therapy Association’s House of Delegates has shifted its position from one that recognizes the right of a PT to make a diagnosis (“may establish” in 1984; APTA HOD, 1984) to one that requires a diagnosis for each patient (“shall establish” in 2007; APTAHOD, 2007) (Box 9-1). However, any diagnosis or classification should be within the legal realm of physical therapy, as defined by state practice acts (Jette, 1990). 1. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, part II: preferred practice patterns (Figure 9-2). The preferred practice patterns defined in the Guide are accepted as diagnoses made by physical therapists. These practice patterns encompass many possible ICD-9 diagnoses. They classify patients according to a clustering of impairments and related health conditions. Example: Impaired motor function and sensory integrity associated with progressive disorders of the central nervous system 2. Classification systems. PTs have become the practitioners who have the appropriate training to develop a proper diagnosis of the causes of movement dysfunction. Much research is currently underway to develop diagnostic classification schemes, or treatment-based classifications, for certain patient populations, including stroke (Scheets et al., 2007), low back dysfunction (Delitto et al., 1995; George & Delitto, 2005; Van Dillen et al., 1998), and neck pain (Fritz & Brennan, 2007). The primary purpose of such classification systems is that subgroups of patients can be identified from key history and examination findings, and these subgroups can then be given distinctively different interventions that are specially suited to their condition. The classification of subgroups is based not on health condition, but typically on a combination of findings at the level of impairments and activities. 3. Disablement systems. Guccione (1991) advocated for diagnosis by PTs to be focused on the relation between impairments and functional limitations, based on the Nagi model. Indeed, we advocated for a similar definition in the first edition of this textbook. With the adoption of the ICF framework and terminology, a more global classification system for considering diagnosis is warranted. We argue that diagnoses within the ICF framework should not just link two of the levels (impairments and activities), but rather include links within all levels of the framework (health condition, body structures and functions, activities and participation, as well as personal and societal factors). Indeed, it has been recently recommended that enablement models should inform but not constrain any diagnostic descriptors that are developed (Norton, 2007).

Documenting the Assessment

Summary and Diagnosis

Diagnosis by Physical Therapists

DEFINITION OF DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

PHYSICAL THERAPY DIAGNOSTIC SYSTEMS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Documenting the Assessment: Summary and Diagnosis,

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue