Distal Interphalangeal, Proximal Interphalangeal, and Metacarpophalangeal Joint Arthrodesis

Charles Cassidy

Jennifer Green

DEFINITION

Conditions resulting in the need for arthrodesis in the hand include arthritis, unreconstructable soft tissue problems, and certain neurologic conditions.

ANATOMY

The proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint configurations are quite similar.

The condylar heads are biconvex but slightly asymmetric, being about twice as wide volarly as dorsally.

The reciprocal bases of the distal segment are biconcave, having a central ridge.

The volar plate extends from the neck of the phalanx to the volar base of the more distal phalanx, preventing joint hyperextension.

Radial and ulnar collateral ligaments provide additional joint stability. The “true” collateral ligaments have bony attachments at both ends, whereas the accessory collateral ligaments extend from the condylar head to the volar plate.

The axis of rotation and radius of curvature for a given interphalangeal joint are fairly constant. Consequently, the true collateral ligaments are effectively isometric, whereas the accessory collateral ligaments resist lateral translation when the joint is extended.

As a result of the ligamentous and bony architecture, the PIP and DIP joints normally function as highly constrained hinge joints.

The extensor tendon crosses the DIP joint dorsally as the terminal tendon, inserting slightly distal to the dorsal base of the distal phalanx.

The germinal matrix of the nail bed is close to the terminal tendon insertion (average of 1.3 mm distal).

The flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon inserts broadly on the volar aspect of the distal phalanx, extending from the base to the midshaft.

Over the PIP joint, the extensor apparatus splits into thirds. Contributions from the extensor tendon, the interosseous tendons, and lumbricals form the central slip, which inserts onto the dorsal base of the middle phalanx. The lateral bands travel past the PIP joint along the lateral margins and then combine to form the terminal tendon distally.

The flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendon splits to insert on the volar lateral margins of the proximal shaft of the middle phalanx.

Unlike the interphalangeal joints, the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are multiaxial, permitting motion in multiple planes.

The metacarpal head has a complex, convex shape. Viewed end-on, the metacarpal head is pear-shaped, being wider volarly. In the sagittal plane, the radius of curvature increases progressively from dorsal to volar.

The metacarpal attachment of the collateral ligaments is dorsal to the axis of rotation. The phalangeal and volar plate attachments are similar to the interphalangeal joint.

As a consequence of the metacarpal head shape and ligament attachments, the MCP joints are typically more lax in extension and tight in flexion.

Significant variability exists in the shape of the thumb metacarpal head. Some heads are more square than round, potentially limiting lateral translation and MCP flexion.

In the thumb, the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) tendon inserts onto the dorsal base of the proximal phalanx. The size of the EPB tendon is variable.

For some patients, the extensor pollicis longus (EPL) tendon assumes the major role in MCP joint extension.

In the other digits, no direct extensor attachment exists. MCP joint extension occurs through a sling effect of the sagittal hood fibers lifting the proximal phalanx through the pull of the extensor tendon.

MCP joint flexion is produced through a combination of direct intrinsic tendon attachments to the volar lateral phalangeal base and indirect actions of the intrinsics on the more distal transverse fibers of the extensor hood.

PATHOGENESIS

Arthritis is the principal indication for small joint arthrodesis.

Osteoarthritis (OA) most commonly affects the DIP joints. It is estimated that at least 60% of individuals older than age 60 years have DIP joint arthritis, which may not necessarily be symptomatic.

In the early stages, the joints may be painful and swollen in spite of normal radiographs. As the arthritis progresses, osteophytes and mucous cysts may develop. Bony prominences (Heberden nodes) and angular deformities in both the coronal and sagittal planes (mallet appearance) may develop. In the final stages, DIP joint motion may be severely restricted.

OA may also involve the PIP joints and the MCP joints, especially in the index and middle fingers.

Inflammatory arthritis may also affect the small joints of the hand. About 70% of rheumatoid patients have hand involvement. Synovitis may result in deformity due to attenuation of supporting structures (collateral ligaments, extensor tendons) long before arthritic changes are evident.

At the DIP joint, terminal tendon incompetence may result in a secondary swan-neck deformity.

At the PIP joint, central slip attenuation results in a boutonnière deformity.

At the MCP joint, collateral ligament involvement may contribute to ulnar drift. Persistent synovitis produces cartilage loss.

Hand involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may mimic rheumatoid arthritis. Supporting structures are affected principally in SLE, which may result in joint subluxation or dislocation with relatively normal-appearing articular cartilage. The capsuloligamentous problems may compromise attempts at joint salvage.

In contrast, psoriatic arthritis may produce a remarkable degree of bone loss as the arthritis progresses. Pencil-in-cup deformity is a characteristic feature of psoriatic arthritis of the interphalangeal joints. Severe bone resorption is the characteristic feature of arthritis mutilans, most commonly seen in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthrodesis is the most reliable method for halting this destructive process.

Scleroderma typically produces PIP flexion and MCP extension contractures. Impaired vascularity of the digits may result in dorsal PIP ulcer formation and central slip attenuation, compounding the PIP flexion deformity.

Presentations of crystalline arthropathy in the small joints of the hand may be varied. The process may be indolent, presenting as gouty tophi over the DIP joint, or acute, presenting as an exquisitely painful, swollen, tender joint. Untreated, gout results in a resorptive arthritis.

Infection is another cause of small joint arthritis.

A “fight bite” directly inoculates the MCP joint and, if undertreated, can result in rapid joint destruction.

Contiguous spread, for example, from a felon or a wound over the DIP or PIP joint may destroy the adjacent joint.

Hematogenous spread is an uncommon cause of septic arthritis in the hand.

Trauma is another cause of unreconstructable problems in the small joints of the hand.

Intra-articular fractures and fracture-dislocations may result in arthritis, particularly in cases of residual joint incongruity. The PIP joint does not tolerate injury well.

Severe periarticular soft tissue injuries may cause severe joint stiffness, even if the underlying joint surface is not initially involved. Certain soft tissue injuries, such as central slip disruptions, may confound attempts at reconstruction.

Central or peripheral nerve injury may produce imbalances in the hand. Arthrodesis can potentially simplify reconstructions in an effort to improve function.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Pain is the most common complaint of patients who are candidates for arthrodesis. Ideally, the location of the pain should correlate with the joint in question.

In OA, multiple DIP joints may appear abnormal, although they may not necessarily be painful.

Polyarticular involvement is common in rheumatoid arthritis. A priority list should be elicited from the patient.

Handedness, occupation, and avocational activities should be documented.

The functional impact of the problem should be clearly defined.

When a single joint is involved, a history of trauma should be sought.

In cases of acute, painful swelling, a history of penetrating injury, gout, or recent infection should be considered.

The physical examination should include the appearance of joints and overlying skin, active and passive range of motion of the affected joints, stability, grip and pinch strength, and sensibility.

The status of adjacent joints should be evaluated.

For example, chronic DIP OA resulting in a DIP flexion deformity may produce a secondary hyperextension deformity of the PIP (swan neck) that may be more disabling than the primary (DIP) problem.

Multiple DIP joint bumps (Heberden nodes) are a characteristic feature of OA.

Mucous cysts are suggestive of underlying DIP OA.

Onycholysis and eczema are suggestive of psoriatic arthritis.

Discrepancies between active and passive motion are indicative of an associated tendon problem.

Stress examination may demonstrate collateral ligament incompetence.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs (posteroanterior [PA], lateral, oblique) of the affected digit are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

In cases of suspected inflammatory arthritis, a collagen vascular screen is ordered. This blood panel includes a rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody (ANA), complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

A uric acid level may be drawn in cases of suspected gout.

Blood tests are not generally helpful in the setting of an acute finger infection.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound may rarely be ordered to evaluate tendon pathology if stiffness is associated with tendon abnormality.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

OA

Inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid, SLE, psoriatic arthritis)

Crystal arthritis

Posttraumatic arthritis

Infection

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The mainstays of nonoperative treatment for unreconstructable small joint problems in the hand include oral medications, splints, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

For OA and posttraumatic arthritis, oral anti-inflammatory agents may reduce pain and stiffness.

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate appear to be of limited value for hand arthritis.

Rheumatoid patients can consider modifications in their medication regimen, supervised by a rheumatologist.

Resting splints may reduce pain and inflammation.

At the DIP and PIP joints, a simple padded aluminum splint may suffice.

Corrective splints, such as the safety pin static progressive or LMB dynamic splint (DeRoyal), will not be tolerated when the joint is inflamed.

For the thumb MCP joint, a hand-based thermoplast splint may lessen discomfort and improve function.

Buddy taping to the adjacent digit may be appropriate for some MCP joint problems. Dynamic MCP joint splints are usually reserved for postoperative protection.

Corticosteroid injections may provide temporary relief of pain and synovitis. The joint may be difficult to access and the joint capacity is quite small.

The surgeon should use a 27-gauge needle and inject 0.5 mL of Celestone Soluspan and 0.5 mL of 1% Xylocaine through a dorsal approach.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Arthrodesis versus Arthroplasty

Arthrodesis is a reliable procedure for managing arthritis and instability of the DIP joint. The functional impairment from loss of motion at the DIP joint is minimal.

At the PIP joint level, the surgeon and patient must weigh the potential benefits of stability and pain relief against the functional impairment resulting from the loss of PIP joint motion. For the index finger, PIP joint stability is critical for pinch. On the other hand, in the small finger, PIP joint mobility is necessary for grip.

As a general rule, for isolated unreconstructable PIP problems, the index finger gets arthrodesis, the middle finger gets arthrodesis or arthroplasty, and the ring and small fingers get arthroplasty.

Exceptions to the rule include associated unsalvageable tendon problems and soft tissue coverage issues, in which arthrodesis may be preferred.

The status of the adjacent joints is an important factor in deciding whether to perform arthrodesis or arthroplasty. In the rheumatoid patient with both MCP and PIP involvement, the temptation is to perform arthroplasties of all involved joints. So-called double-row arthroplasties tend to compromise the results at both the MCP and PIP joints. In such instances, the goal is stability at the PIP joint (arthrodesis) and motion at the MCP joint (arthroplasty).

Arthrodesis of the thumb MCP joint is a reliable procedure for managing arthritis and unreconstructable ligament problems. Arthrodesis is a far superior procedure to arthroplasty for the thumb. However, before undertaking this, it is important to ensure adequate motion and function of the adjacent joints (interphalangeal, carpometacarpal).

The chronic radial collateral ligament tear with static volar ulnar subluxation is a good indication for thumb MCP fusion.

Arthrodesis of the digital MCP joints is not commonly performed. Indications include multiple failed arthroplasty or inadequate bone stock for arthroplasty, unrelenting infection, refractory instability of the index MCP, and an unreconstructable extensor mechanism.

Candidates for arthrodesis must understand that all motion in the affected joint will be eliminated and that the principal goals are pain relief and stability.20

Arthrodesis Position

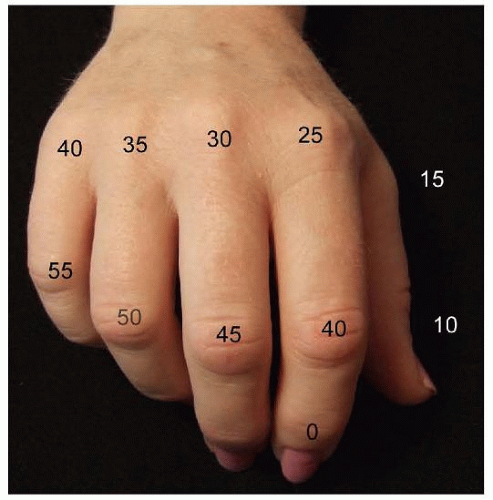

The fusion position varies with the digit and joint involved. Invariably, the decision is a compromise between appearance and function. The ideal posture should replicate the normal digital cascade (FIG 1).

In general, the DIP joints and thumb interphalangeal joint should be fused in 0 to 10 degrees of flexion.15

For the PIP joint, some authors recommend a uniform 40-degree flexion position for all digits,6 whereas others recommend 40 degrees for the index finger, progressing ulnarward in 5-degree increments to 55 degrees in the small finger.18

Many prefer a slightly more extended position for the index PIP that will still allow functional tip-to-tip pinch.

The recommended fusion angle of the MCP joints is a cascade from 25 degrees of flexion in the index digit, progressing ulnarward in 5-degree increments to 40 degrees in the small finger.15

The recommended fusion angle of the MCP joint of the thumb is 10 to 15 degrees of flexion and just resting at the radial border of the index finger mid-distal phalanx.15

Fixation Options

The choice of surgical technique depends on a number of factors, including the affected joint to be fused, the availability and cost of implants, the adequacy of bone stock, and the comfort of the surgeon. The goal is to achieve a solid fusion of the affected joint in a timely manner. Bone preparation is essential.

The specific method of fixation may be less important in obtaining union than specific patient factors such as bone quality. Certain constructs, such as the tension band, are more rigid but may be associated with more hardware-related problems.

The biomechanical issues must be weighed against potential soft tissue problems when deciding on a form of fixation. Maintenance of motion in the adjacent joints is critical.

Kirschner wire fixation has been associated with fusion rates of up to 99%.

Advantages

Simplicity of the technique

Ready availability of low-cost implants

Disadvantages

Infection risk, including superficial pin site and deep wound infections, osteomyelitis; pin migration; minimal compression across the fusion site

Interosseous wiring has been found to be biomechanically stronger than Kirschner wire fixation.19 It is especially useful for PIP fusion and thumb interphalangeal fusion.

Advantages

Biomechanically stronger than Kirschner wire fixation19

Readily available low-cost implants

Disadvantages

Large amount of soft tissue stripping for appropriate placement of drill holes

Higher rate of nonunion, up to 9%12

Tension band fixation is a biomechanically stable method of fixation17 combining parallel Kirschner wires for rotational control and interosseous wiring for compression. This technique is especially useful for MCP, PIP, and thumb interphalangeal arthrodesis.

The tension band construct converts the strong distracting force created by the finger flexors to a compressive force across the arthrodesis interface.

This technique is relatively simple, with a high fusion rate and reliable outcomes,1,17 especially when used for arthrodesis of the MCP and PIP joints.

Postoperative immobilization is necessary only in the immediate postoperative period to allow for healing of the incision.1,9

Advantages

Simplicity of the procedure

Low rate of infection17

Readily available, low-cost implants

Enhanced biomechanical stability and strength of the construct, allowing for early active range of motion.17 The tension band construct for small joint arthrodesis has been shown to be biomechanically superior compared to crossed Kirschner wire fixation and intraosseous wiring, especially in anteroposterior bending and in axial torsion.10

Disadvantages

Increased soft tissue dissection to place the drill holes, with resultant increased risk of soft tissue and tendon scarring

Difficult to remove fully internalized hardware if necessary

Plate fixation provides biomechanically strong fixation, especially useful for PIP and MCP joint arthrodesis.4,20

Advantages

Excellent fusion rate by 6 weeks, 96% to 100%17

Ability to correct deformity

Useful in cases with segmental bone loss4

Disadvantages

Technically demanding

Time-consuming

Extensor tendon adhesions, possibly necessitating hardware removal and tenolysis17; stiffness in adjacent joints

Hardware prominence

Compression screw fixation is a biomechanically strong fixation technique21 that is especially useful for arthrodesis of the finger DIP and PIP joints as well as the thumb interphalangeal joint.

Recent biomechanical studies suggest that an intramedullary linked screw (Extremity Medical, Parsippany, NJ) is stronger than current plate and tension band constructs for PIP arthrodesis. It does, however, sacrifice considerable bone.5

Using a headless screw keeps the fixation hardware low profile and prevents the problems associated with prominent hardware.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree