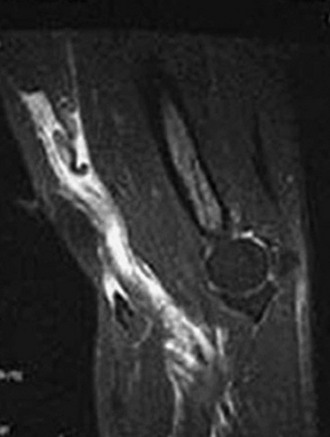

Chapter 50 The distal, insertion, bicipital tendon ruptures relatively infrequently, with an incidence of 1.2 ruptures per 100,000 person-years.1 Proximal tendon ruptures are far more common, accounting for 97% of all biceps tendon ruptures.1 However, when distal ruptures do occur, they affect the dominant arms of highly functioning men aged 40 to 60 and can be associated with substantial functional and financial disability owing to chronic pain and weakness in forearm supination and elbow flexion.2,3 Although nonoperative treatment2,3 and tenodesis to the brachialis originally were suggested as treatment options for distal biceps ruptures,4 anatomic reconstruction with repair of the biceps to the bicipital tuberosity on the proximal radius has led to excellent functional outcomes, high patient satisfaction, and restoration of strength and endurance in forearm supination and elbow flexion in numerous clinical series.1–14 Boyd and Anderson’s original description of such a repair involved two incisions and fixation via an osseous bridge.15 However, whereas injury to the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) may have been lessened with this technique, this method led to an unacceptably high incidence of heterotopic ossification and synostosis of the radius and ulna.3,4,13,16 Thus the anterior, single-incision procedure has risen in popularity.7,10,11,14 Fixation methods have also evolved, first with the use of suture anchors11,14 and more recently with the EndoButton (Acufex, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA).6,12,17,18 The EndoButton has been demonstrated to be biomechanically superior to suture anchors by a factor of two and to an osseous bridge by a factor of three, and allows construct “prefabrication” outside of the wound.11 In addition to success with repair of acute lesions, recently good outcomes have been demonstrated in the repair of chronic ruptures with grafting for the gap between the shortened tendon and the anatomic insertion.8,10,12 Whereas complete ruptures are more common, not all injuries to the distal tendon involve a complete discontinuity, and some injuries may involve partial residual continuity of the tendon.17 Although similar in symptomatology, these “partial” injuries are considerably more difficult to diagnose. Diagnosis relies on advanced imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).17 Partial rupture exists on a spectrum with several poorly understood diagnoses including cubital bursitis, bicipital tendinosis, and biceps paratendinitis, each of which can exist in isolation or can coexist with a distal biceps tendon rupture.17 In the acutely ruptured distal biceps tendon, the examiner may observe diffuse swelling and ecchymoses radiating from the antecubital fossa. Acutely, guarding caused by pain may make provocative testing difficult. Once the acute inflammation has resolved, the patient may notice a change in the contour of the arm (Fig. 50-1) resulting from proximal retraction of the biceps.1 Several physical examination maneuvers rely on palpation of the distal biceps tendon. The examiner may be able to palpate a defect within the tendon by attempting to “hook” an index finger around the distal biceps tendon in the flexed and supinated arm. This “hook” sign can be more difficult to elicit if the lacertus fibrosus remains intact. While palpating, the examiner can then supinate and pronate the patient’s arm with the other hand, which should cause proximal and distal movement, respectively, of the junction of the distal biceps tendon and the biceps muscle belly. If no motion of this junction can be appreciated with forearm rotation, the examiner should consider a distal biceps rupture. In a similar test of the “tenodesis effect” of the tendon distally and the muscle belly proximally, the examiner may manually compress the biceps muscle with the arm relaxed in 90 degrees of elbow flexion and neutral forearm rotation to slight pronation to place the biceps muscle under tension. This “squeeze” should cause an obligate supination of the forearm, analogous to the Thompson test in the calf for Achilles tendon rupture. This test has been shown to have a high sensitivity and a low false-positive rate, although its specificity is as yet undetermined.19 Whereas active, resisted forearm supination and elbow flexion will often be objectively weak compared with the contralateral uninjured side, a lack of weakness does not exclude tendon rupture, because other muscles such as the supinator and brachialis can also account for these motions.1 Radiographic imaging infrequently contributes to the diagnosis, although obtaining anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views is crucial for exclusion of other osseous pathology. In addition, radial tuberosity avulsion fracture can have a similar presentation, and therefore the examiner must scrutinize the images closely for this easily missed diagnosis. With chronic distal biceps tendon ruptures, the radial tuberosity may undergo hypertrophic changes.1 In patients in whom the history and physical examination findings convincingly yield a diagnosis of distal biceps tendon rupture, no further imaging need be obtained. However, MRI can be helpful when the diagnosis is unclear or when a partial rupture is suspected.17,20 These images can also aid surgical planning, because a proximal rupture may indicate a more proximal approach. Common MRI findings include discontinuity of the tendon with distal absence, increased T2 signal in the sheath indicating inflammatory fluid, increased T2 signal within the muscle, and a mass within the antecubital fossa resulting from the retracted proximal tendon end (Fig. 50-2). In more chronic setting, atrophy of the biceps muscle may be seen, as well as thinning or thickening of the remainder of the tendon.17,20 Because this tendon does not travel in the traditionally defined anatomic axes, MRI in the flexed, abducted, and supinated position can be a useful adjunct.17 In the setting of a partial tear, MRI can be used to determine the extent of the tear. MRI may lack sensitivity and not correlate with intraoperative findings. In persistently symptomatic patients with strong clinical findings, MRI should be used as an adjunct to decide the course of treatment. Anecdotally, intraoperative findings have revealed larger tears than otherwise appreciated on MRI. MRI can also be useful to assess for associated pathology such as bicipital tendinosis, bursitis, paratendinitis, hematoma, or contusion. Ultrasound may play a role in diagnosis owing to its cost-effectiveness and reliability. However, this technique is operator dependent and thus continues to be institution specific. Nonoperative treatment consistently leads to persistent functional deficit and anterior elbow pain.2,3 Such deficits may be well tolerated in low-demand individuals such as the elderly and the sedentary, particularly in the nondominant extremity. In some individuals with extensive medical comorbidities, the risk of operative intervention may outweigh these known functional deficits. However, in the majority of young, healthy, active individuals who sustain distal biceps ruptures, surgical repair should be strongly considered.1–14 Preoperatively, the surgeon must identify (1) whether the injury is acute or chronic, (2) whether the lacertus fibrosus is intact, (3) whether the tear is complete or partial, and (4) whether the discontinuity is at the myotendinous junction, tendon midsubstance, or bicipital tuberosity. Chronic tears not infrequently present a surgical challenge owing to retraction of the tendon and scarring of the peritendinous tissues (which may include the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve), alteration of the anatomy, and decreased tensile properties of the tissue after extended lack of use. In this setting the surgeon must either have a plan for the harvest of autograft tendon tissue or have allograft tissue available for reconstruction.8,10,12 Partial tears warrant a trial of conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, immobilization, and rehabilitation. However, the surgeon may wish to determine the extent of the tear with MRI, ultrasound, or, as has been reported, bursoscopy.17 Distal biceps tendon tears that involve more than 50% of the tendon may be indicated for completion of the tear and anatomic repair to the bicipital tuberosity, whereas tears with more than 50% of the tendon in continuity can be considered for debridement.17 The most accurate method to determine the extent of the repair remains a subject of debate.17

Distal Biceps Repair

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine