Dislocations and Chronic Volar Instability of the Thumb Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Robert R. Slater Jr.

DEFINITION

Disruption of the restraining structures on the volar surface of the joint between the metacarpal and proximal phalanx of the thumb may result in excessive joint motion and abnormal hyperextension.

Often painful, this instability frequently causes significant functional deficits because so much of what humans do with their hands depends on having a stable, pain-free thumb to oppose the other digits.

Acute injuries, including joint dislocations, must be treated correctly and promptly to afford the best chance for successful outcomes.

Chronic volar instability is seen less often than is collateral ligament incompetence, but it should not be overlooked. It can be treated effectively with a variety of techniques which will be discussed in this chapter.

ANATOMY

The thumb metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint has features of both a ginglymus (hinge) joint and a condyloid joint. The joint moves mostly in a flexion-extension mode (ginglymus style), but there are also elements of rotation and abduction-adduction in the normal joint (condyloid).

Thumb MP joint motion varies widely from individual to individual because of the spectrum of metacarpal head geometry seen in “normal” hands.

Some metacarpal heads are more rounded and allow greater flexion, extension, and rotation, whereas others are flatter and allow relatively less range of motion (ROM).

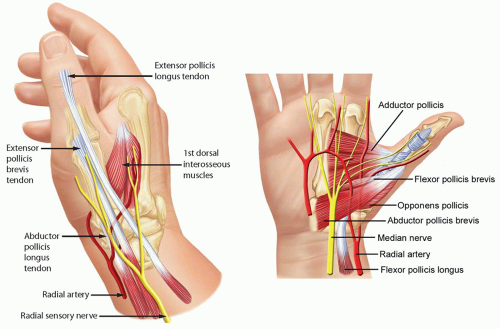

The joint derives its stability mostly from soft tissue constraints not bony architecture (FIG 1).

The proper collateral ligaments originate from the region of the lateral condyles of the metacarpal and pass palmarly and obliquely to insert on the palmar portion of the proximal phalanx.

The accessory collateral ligaments originate from the same region but slightly more proximal and traverse distally and palmarly in an oblique fashion to insert on the volar plate and sesamoids.

The volar plate serves as the floor of the MP joint. The adductor pollicis (AdP) inserting into the ulnar sesamoid at the distal edge of the volar plate and the insertions of the flexor pollicis brevis (FPB) and abductor pollicis brevis (APB) into the radial sesamoid at the radial distal edge of the volar plate provide additional volar support.

The AdP, FPB, and APB also contribute fibers to the extensor mechanism by way of the adductor and abductor aponeuroses and thus provide a modicum of lateral joint stability.

Dorsally, the extensor pollicis brevis inserts onto the base of the thumb proximal phalanx and the extensor pollicis longus inserts at the base of the thumb distal phalanx; both traverse the MP joint and add to the stabilizing forces surrounding the joint.

The MP joint capsule itself surrounds the joint and contributes slightly to stability.

PATHOGENESIS

The typical mechanism is a hyperextension force strong enough to rupture the volar plate and joint capsule.

For example, dislocations may occur when a ball strikes a player’s thumb or when there is a direct blow or fall that drives the proximal phalanx into sudden hyperextension.

Occasionally, the radial or ulnar collateral ligaments (or both) of the MP joint are ruptured along with the volar plate. Their treatment is addressed in other chapters.

Sometimes, the instability occurs in the setting of a patient with generalized ligamentous laxity such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (or other collagen disorders), but in those situations, symptoms are less common and patients typically learn to compensate for the joint laxity.

NATURAL HISTORY

Posttraumatic instability left untreated may result in weakness of pinch and grip and progress to painful arthrosis due to the abnormal biomechanics of the damaged joint.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

In traumatic cases, it is important to inquire about the mechanism of injury.

If patients recall which way the thumb was “pointing” at the time of injury, it helps the examiner determine which structures were likely injured.

With the ubiquitous presence of cell phone cameras and digital cameras, photos of the deformity right after the injury are often available and can be helpful in confirming the suspected injury.

Was the joint dislocated and did it reduce spontaneously or with assistance from a coach, trainer, or the patient?

How difficult was the reduction?

Physical examination should include an assessment of ROM and grip and pinch strength, particularly in comparison with the contralateral thumb. Focal areas of tenderness should be ascertained. Residual tenderness along the volar plate may persist long after the injury.

The examiner should observe the resting joint posture; dislocated joints exhibit obvious deformity.

The examiner should check for open wounds and assess the vascular status. Open wounds or vascular compromise mandate emergent treatment.

Limited or absent interphalangeal joint ROM suggests flexor pollicis longus tendon entrapment.

Dislocated or painful MP joints will have limited ROM.

Volar plate stability is assessed because instability must be recognized and treated appropriately to maximize outcomes.

Severe collateral ligament injury is uncommon in conjunction with volar plate instability but must be recognized and treated where indicated.

An acute dislocation is rarely subtle, but when patients present with chronic instability symptoms, there may be guarding against full joint extension and soft tissue thickening in areas of chronic pathology.

IMAGING AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs of the thumb in three views (anteroposterior [AP], lateral, and oblique) are requisite.

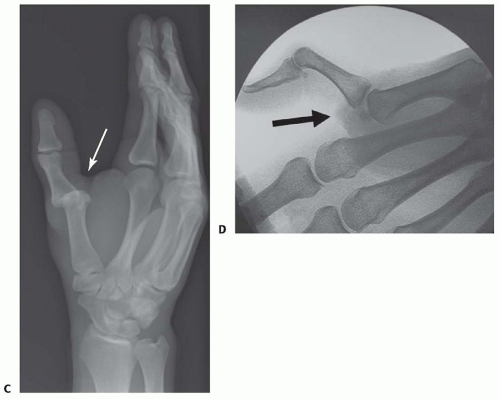

Injury films will reveal the direction of joint dislocation and any associated fractures (FIG 2A-C).

FIG 2 • (continued) C. Oblique injury film of the thumb (vs. hand) shows a dorsal MP joint dislocation (arrow). D. Fluoroscopic imaging shows joint instability.

In the chronic setting, films may show evidence of prior fractures or bony injuries as well as the positions of the sesamoid bones relative to the joint space. In cases of chronic volar plate instability, the proximal phalanx may show subtle dorsal subluxation on the metacarpal head (that is more commonly noted when there has been injury to the dorsal capsule in association with collateral ligament damage).

Arthritic changes at the MP joint seen on the plain films will alter the treatment options. If the chronically unstable joint is already arthritic at the time of presentation, then an arthrodesis will be a better option than a soft tissue reconstruction.

Fluoroscopic real-time imaging and stress testing may confirm the suspected joint instability (FIG 2D).

A digital block may be placed to facilitate an adequate examination.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Fracture

Collateral ligament injury

Ligament laxity, generalized (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome)

Arthritis

Locked trigger thumb (stenosing tenosynovitis)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most acute thumb MP dislocations can be reduced via closed means, avoiding surgery.

The reduction maneuver for a dorsal dislocation usually requires only slight hyperextension to gently “unlock” the proximal phalanx from its perch on the metacarpal head, followed by direct volarly and distally directed pressure on the base of the proximal phalanx to gently slide it over the metacarpal head to achieve reduction.

Subtle, slight rotation (pronation and supination) at the same time may help ease any interposed soft tissue out of the way as the phalanx reduces.

Longitudinal traction and excessive hyperextension should be avoided because the soft tissue tension generated may cause one or more structures surrounding the joint to slip between the metacarpal head and the proximal phalanx, blocking reduction.

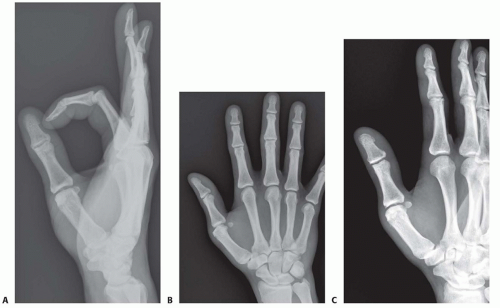

Once the joint is reduced, the patient should be able to flex and extend the thumb joints and the radiographs should show concentrically reduced and congruent joint surfaces (FIG 3).

If either of those conditions is not met, it suggests there may be residual soft tissue interposed in the joint, an indication for open reduction.

After successful closed reduction, the thumb should be splinted in flexion to relax the injured volar structures.

After a few days, when the acute swelling has dissipated, the splint may be changed to a thumb spica cast, again with the MP joint flexed, for an additional 2 to 3 weeks. Rehabilitation can commence thereafter, emphasizing ROM exercises within a safe zone of motion from full flexion to just short of neutral extension and then increasing gradually to unrestricted ROM and hand use by 6 weeks after injury.

For patients engaged in activities that risk forced hyperextension of the thumb such as ball sports, taping or splinting

may be required during these activities for several additional weeks.

FIG 3 • A-C. Postreduction views of the patient in FIG 2 confirm congruent joint surfaces and satisfactory alignment, including the sesamoid bone positions.

Failure to recognize or treat the acute instability or overly aggressive progression to full, unlimited hand use may result in chronic volar instability.

Nonoperative management then is limited to providing the patient with a custom-molded splint to prevent hyperextension of the MP joint.

A properly trained hand therapist is invaluable in assisting patients who prefer to manage the problem nonoperatively and use a protective splint rather than proceeding with surgical treatment for their chronic instability.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Open reduction is required when attempts at closed manipulation and reduction of acute dislocations fail.

Failure is typically the result of soft tissue interposition in the joint that blocks reduction. Tissue interposition may have happened at the time of the original injury or as a result of a well-meaning coach, friend, or medical colleague trying to reduce the dislocation by applying vigorous traction, which can cause the soft tissues to become incarcerated.

Chronic instability, which is persistently symptomatic despite nonoperative treatment, is best treated with a soft tissue stabilization technique unless moderate to severe arthrosis is present or the instability is global and exceedingly severe. In those cases, arthrodesis is the treatment of choice.

Preoperative Planning

The physician should review all imaging studies. In most cases, those will be limited to plain radiographs and perhaps spot films from fluoroscopic evaluations.

Films should be reviewed for any bony abnormalities, especially nondisplaced fractures. One should avoid fracture displacement during intraoperative manipulation of the thumb.

In fracture-dislocations of the MP joint, larger fragments are stabilized using Kirschner wires or screws and smaller avulsion-type fragments are excised and the ligament is secured to the bone.

For chronic cases, it is important to review the films and rule out osteoarthrosis, which would warrant different treatment strategies.

Examination under anesthesia with the assistance of fluoroscopy can be useful to confirm the degree and direction of joint instability.

Spot films obtained before and after surgical stabilization can be helpful visual aids for use in postoperative discussions with the patient and his or her family to explain again the nature of the problem and how it was treated.