This article is a guideline covering a wide array of cervical conditions seen in the workers’ compensation, as well as the nonworkers’ compensation, population. The guideline is intended to provide a diagnostic and treatment algorithm to commonly seen cervical conditions such as single-level and multilevel radiculopathies and myelopathies.

Key points

- •

The surgical treatment of degenerative discs is generally discouraged.

- •

Symptomatic cervical radiculopathies can improve with nonoperative management.

- •

The decision to pursue surgery, or surgical consultation, is appropriate when myelopathic symptoms are present.

Introduction

The following guideline is intended as a community standard for health care providers who treat injured workers or others with symptomatic cervical pathology. The guideline aims to help ensure that the diagnosis and treatment of cervical neck conditions are of the highest quality. The emphasis is on accurate diagnosis and curative or rehabilitative treatment.

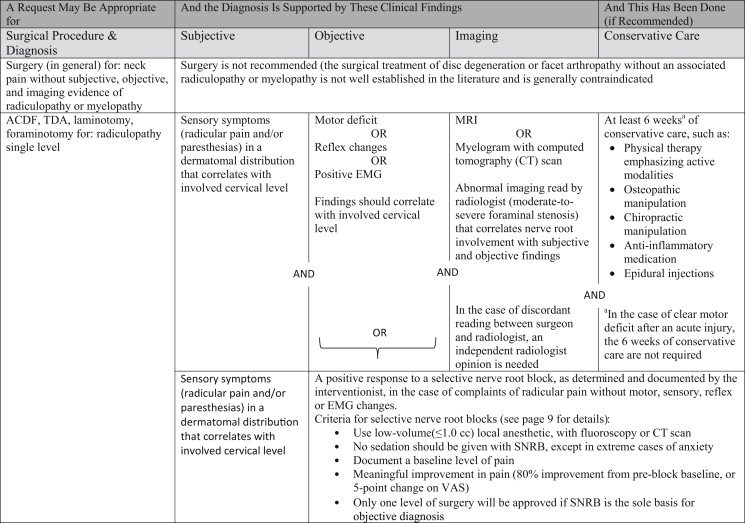

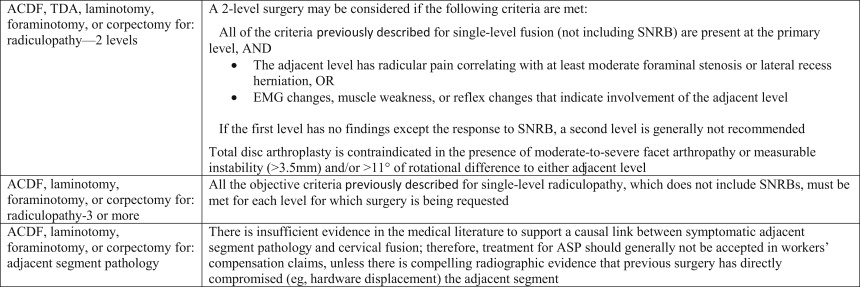

The recommendations are based on the best available clinical and scientific evidence from a systematic review of the literature, and on a consensus of expert opinion when scientific evidence was insufficient. The following table summarizes the recommendations:

Introduction

The following guideline is intended as a community standard for health care providers who treat injured workers or others with symptomatic cervical pathology. The guideline aims to help ensure that the diagnosis and treatment of cervical neck conditions are of the highest quality. The emphasis is on accurate diagnosis and curative or rehabilitative treatment.

The recommendations are based on the best available clinical and scientific evidence from a systematic review of the literature, and on a consensus of expert opinion when scientific evidence was insufficient. The following table summarizes the recommendations:

Background and prevalence

Neck-related pain is common in both the workers’ compensation and general populations. Many cases of axial neck pain are temporary and will resolve with time and nonoperative treatment. It can be difficult to distinguish between an acute or chronic condition related to work and the chronic pain and degeneration associated with aging.

Cervical degenerative disc disease (DDD) is a common cause of pain and disability, affecting approximately two-thirds of the US adult population. Most symptomatic cases present between the ages of 40 and 60, although many individuals never develop symptoms. MRI studies have documented the presence of DDD in 60% of asymptomatic individuals aged greater than 40 years and 80% of patients over the age of 80 years ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). Previous neck injuries, cervical strains, and arthritis increase the risk of developing DDD, which may result in the development of abnormal bony spurs (spondylosis). Less commonly, cervical DDD progression and its sequelae may directly compress parts of the spinal cord (myelopathy), affecting gait and balance. It may also result in foraminal narrowing, compressing the exiting nerve root (radiculopathy), resulting in a dermatomal distribution of numbness, pain or parasthesias, or a myotomal distribution of weakness ( Figs. 3 and 4 ).

Treatment options for DDD include conservative and surgical measures. In the general population, the rate of surgery for degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine increased 90% between 1990 and 2000. In elderly patients in the United States, rates of cervical fusions rose 206% between 1992 and 2005. Annual costs for anterior cervical fusions increased 3 fold ($1.62 billion to $5.63 billion) between 2000 and 2009.

Establishing work-relatedness

The etiology of radiculopathies and myelopathies can be multifactorial or unknown. A cervical condition presenting with a history of radiating arm pain, scapular pain, diminished muscle stretch reflexes, loss of sensation, or motor weakness may be classified as an occupational injury or occupational disease depending upon the circumstances giving rise to the condition. If there was a single inciting event that occurred within the work environment resulting in objective medical findings, the condition is likely the result of an occupational injury. If there was no single inciting event, the condition may have risen as the result of an occupational disease. The pain and other manifestations of both industrial injuries and occupational diseases generally become evident within 3 months of the inciting event. For this reason, a condition reported for the first time more than 3 months after a patient was first seen by a provider may not be industrially related. Attribution of such a condition to an industrial event should be based upon careful analysis and thoroughly documented.

Cervical Conditions as Industrial Injuries

Mechanisms of injury to the cervical spine may include distortion of the neck caused by sudden movement of the head, being struck by an object, or a fall from a height. Examples of these injuries include motor vehicle crashes, high impact accidents, explosions, and gunshots.

An acute injury to the cervical spine should be clinically diagnosable as work-related within 3 months of the injury. For an injury claim to the neck to be accepted beyond 3 months, the attending provider should be able to present substantial evidence linking symptoms directly to the initial industrial injury. Claims with insufficient documentation linking clinical symptoms to the initial industrial injury beyond 1 year should generally not be accepted.

Cervical Conditions as Occupational Diseases

Cervical spine conditions may also develop as a natural consequence of aging, resulting in the deterioration of the cervical disc. To establish a diagnosis of an occupational disease all of the following are required:

- 1.

Exposure—workplace activities that contribute to or cause cervical spine conditions

- 2.

Outcome—a diagnosis of a cervical spine condition that meets the diagnostic criteria in this guideline

- 3.

Relationship—for a cervical condition to be allowed as an occupational disease, the provider must document that, based on generally accepted scientific evidence, the work exposures created a risk of contracting or worsening the condition relative to the risks in everyday life, on a more-probable-than-not basis ( Dennis v. Dept. of Labor and Industries , 1987). In epidemiologic studies, this will usually translate to an odds ratio (OR) of at least 2.

Making the diagnosis

History and Clinical Examination

The classic presentation of cervical radiculopathy includes radiating arm pain, scapular pain, diminished muscle stretch reflexes, loss of sensation, and motor weakness, with or without neck pain. Cervical myelopathy is characterized by loss of motor control, hand clumsiness, gait disturbances, spasticity, and bowel or bladder dysfunction.

Diagnostic Testing—Imaging/Myelogram/Electromyographys

Requirements for diagnostic testing and imaging are specified in the criteria table. The basis for the selection of a diagnostic imaging procedure should be based on the information obtained from a thorough clinical examination.

Selective Nerve Root Blocks

Selective nerve root blocks (SNRBs) are only considered criteria for surgery when a worker presents with radicular pain, imaging findings, and a history of 6 weeks of conservative care (as in the criteria table), but does not have the objective signs of motor, reflex or EMG changes. SNRBs should be used only under particular circumstances:

- •

The worker has clear sensory symptoms indicative of radiculopathy or nerve root irritation.

- •

The worker’s symptoms and examination findings are consistent with injury or irritation of the nerve root that is to be blocked.

- •

Injury or irritation of the nerve root to be blocked has not been shown to exist by electrodiagnostic, imaging, or other studies.

It is recommended that the provider giving the injection has the principal responsibility to document the outcome of the selective nerve root block. The provider should

- •

Perform a preinjection examination and document the pain intensity using a validated scale

- •

Explain to the worker the use and importance of the postinjection pain diary

- •

Use low-volume local anesthetic (≤1.0 cc) without steroid for the selective nerve root block; conscious sedation should not be used in the administration of SNRBs, except in cases of extreme anxiety. If sedation is used, the reason(s) must be documented in the medical record, and the record must be furnished to the department or self-insurer

- •

Administer the selective nerve root block using fluoroscopic or computed tomography (CT) guidance. An archival image of the injection procedure must be produced, and a copy must be provided to the department or self-insurer ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5

Fluoroscopic image during a selective nerve root block demonstrating contrast dye outlining the region of injection along the C7 nerve.

- •

Onset (within 1 hour) of pain relief should be consistent with the anesthetic used; duration generally lasting 2 to 4 hours.

- •

Keep the worker in the office for 15 to 30 minutes after the injection if possible, and assist with starting the pain diary.

- ○

Immediately preceding the block, the worker should record the level of pain using a validated scale. Every 15 minutes thereafter, for at least 6 hours following injection, the worker should indicate his or her level of pain. For the remaining waking hours during the 24 hours following the administration of the block, hourly documentation of pain levels is desirable.

- ○

An example of a pain diary is included in this guideline. Pain must be measured and documented using validated tools such as a visual analog scale or a 10-point scale. See labor and industries (L&I’s) opioid prescribing guideline ( www.opioids.LNI.WA.GOV ) for a 2-item graded chronic pain scale, which is a valid measure of pain and pain interference with function.

- ○

- •

Document the effect of the block.

- ○

A positive block is indicated by

- ▪

An overall 80% improvement in pain or pain reduction by at least 5 points on a 10-point scale or visual analog scale

- ▪

Pain relief that lasts an amount of time consistent with the duration of the anesthetic used

- ▪

- ○

A negative block may be indicated by

- ▪

No pain relief or less than 5 points on a 10-point scale or visual analog scale

- ▪

Pain relief that is inconsistent in duration with the usual mechanism of action of the local anesthetic given

- ▪

- ○

- •

Ensure that the surgeon and the department or self-insurer receive the previously described information.

If the block is negative, surgery is generally not recommended. Only 1 level of surgery should be considered if the sole basis of the objective diagnosis is the SNRB.

Treatment

Conservative Treatment

Conservative management of cervical radicular symptoms may include active physical therapy, osteopathic manipulation, chiropractic manipulation, traction, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroid injections.

- •

There is some evidence that an active treatment approach results in better outcomes. Physical therapy accompanied by home exercise for 6 weeks has been shown in a randomized trial to substantially reduce neck and arm pain for patients with cervical radiculopathy.

- •

Steroid injections may provide short-term pain relief for patients with radiculopathy, although they are not without risks. The injection typically includes both steroid and a long-acting anesthetic. See Washington States L&I’s guideline on spinal injections at http://www.lni.wa.gov/ClaimsIns/Providers/TreatingPatients/TreatGuide/spinal.asp .

There is a warning about epidural steroid injections. On April 23, 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) put out a warning that the injection of corticosteroids into the epidural space of the spine may result in rare but serious adverse events, including loss of vision, stroke, paralysis and death (FDA Drug Safety Communications 4-23-2014).

Surgical Treatment

The ideal surgical approach for radiculopathy related to herniated disc remains a matter of debate. Various studies have compared the different surgery types and found no significant difference among them. Cervical surgeries can be divided into 2 major approaches: anterior (with or without fusion) and posterior.

Anterior cervical decompression alone

Discectomy is a surgical procedure to remove part of a herniated disc to alleviate pressure on the surrounding nerve roots. Discectomy is generally a safe procedure with associated risk such as dysphagia, pseudoarthrosis, and nerve damage. Studies, albeit dated, comparing discectomy with discectomy plus fusion have found no statistically significant difference between simple discectomy and discectomy followed by fusion in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy.

Posterior surgeries

Posterior cervical laminotomy/foraminotomy is a highly effective therapeutic procedure for both myelopathy and radiculopathy, as it maintains cervical range of motion, and minimizes adjacent segment degeneration. Kyphosis, incomplete neurologic decompression, and continued persistent neck pain have been concerns with posterior foraminotomies, but studies have shown it to be comparable to anterior cervical discectomy with fusion (ACDF) in clinical outcomes.

Anterior cervical discectomy with fusion

Anterior cervical fusion surgery has become a standard treatment for cervical disc disease, and it is a proven intervention for patients with myelopathy and radiculopathy as it affords the surgeon the ability to provide direct (from the discectomy) and indirect (through restoration of disc height) decompression and stabilization. Various implant and graft devices have been developed for use with ACDF.

Total disc arthroplasty

Total disc arthroplasty (TDA) has been proposed as a viable alternative to ACDF. The theoretic basis for cervical arthroplasty is that it maintains motion and may decrease the likelihood of adjacent segment disease and therefore reduce the rate of reoperations. Various studies have shown similar outcomes for ACDF and TDA.

TDA is not indicated for cervical disease at more than 2 levels. Various devices have FDA approval for single-level TDA, and the FDA has also approved a single devise maker for 2-level adjacent disc arthroplasty in 2013. These devices are indicated for skeletally mature patients for reconstruction of disc following discectomy at a single level or adjacent (in the case of the Mobi-C) levels for radiculopathy or myelopathy. Patients should have failed 6 weeks of conservative treatment or demonstrate progressive signs and symptoms.

Multilevel surgeries

For radiculopathy, a multilevel (2 levels or more) surgery may be considered if all of the criteria for a single-level surgery, not including SNRBs, are present at each level being considered for surgery. Multilevel fusion for myelopathy is more common and may be done if indications are met ( Figs. 6 and 7 ).