CHAPTER 8 Developing and maintaining a pressure ulcer prevention program

1. Explain three justifications for a pressure ulcer prevention program.

2. Distinguish between an avoidable and an unavoidable pressure ulcer.

3. List components of a best practice bundle of a pressure ulcer prevention program.

4. Distinguish between a pressure ulcer risk assessment and a skin assessment.

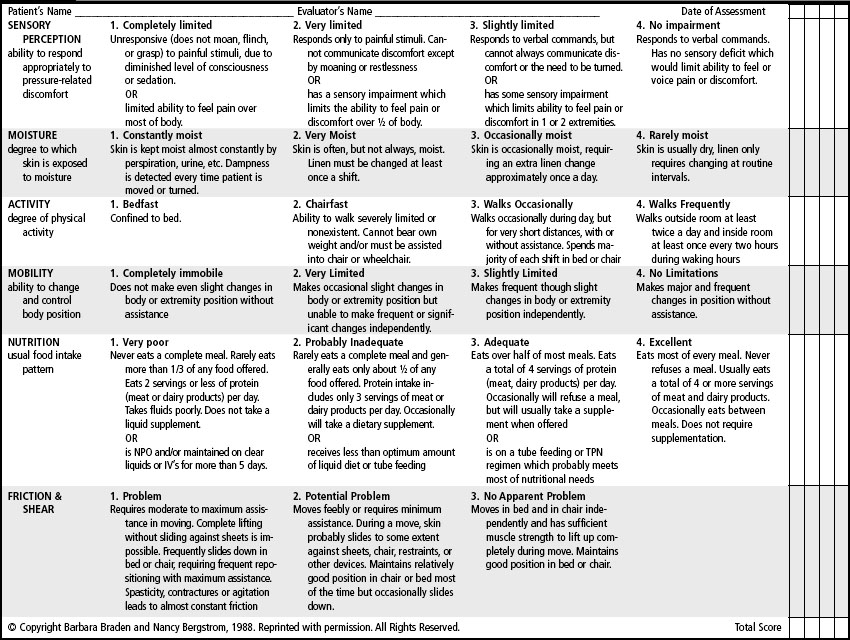

5. Identify the risk factor subscales in the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk.

6. Distinguish between turning and repositioning.

7. Describe five repositioning techniques.

8. Describe why infrastructure is important to the maintenance of a successful pressure ulcer prevention program.

9. Provide examples of how an organization demonstrates skin safety as an organizational priority.

Pupp justification

National priority

As early as 2000, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000) document, Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health, listed reducing pressure ulcer incidence as an objective for all health care providers. According to the National Priorities Partnership (2008), medical errors kill 98,000 Americans each year and are a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States, with an estimated cost of $17 to $29 billion per year. It is estimated that the United States spends approximately $11 billion on pressure ulcers alone each year (Redelings et al, 2005). These statistics are startling when we consider the fact that people come to the hospital when they are ill, trusting that they will be taken care of and protected from adversities. Medical errors that are clearly identifiable, preventable, and associated with serious consequences have been termed never events by the National Quality Forum. In its mission to “fundamentally transform health care,” the National Priorities Partnership, which consists of members from 26 different national organizations and is convened by the National Quality Forum, announced six national priorities to direct health care reform to eliminate waste, harm and inequities. Safety (the elimination of errors whenever and wherever possible) is one such priority and incorporates severe pressure ulcers, defined as Stage III or IV (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2008). The IHI also identified the prevention of pressure ulcers as one of the 12 interventions in its 5 Million Lives campaign (Duncan, 2007).

These positions represent a dramatic shift in public policy. Pressure ulcer prevention has been in the mission of the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses (WOCN) Society (previously known as the International Association for Enterostomal Therapy [IAET]) and is included in the curriculum for WOC nursing education programs since 1982 (Alterescu, 1991; Goode, 1991; IAET, 1987; Wright, 1991). As new technology evolved, risk assessment refined, and pressure ulcer prevention interventions better understood, it was generally accepted by wound care experts that all pressure ulcers could be prevented and that their presence was a reflection on quality of care. In fact, the 5 Million Lives campaign by the IHI launched in 2007 specifically states “the goal for pressure ulcer incidence should be zero” (Duncan, 2007). Most recently, the concept of attaining a zero incidence of facility-acquired pressure ulcers is increasingly being challenged.

Reimbursement for present on admission only

In addition to the effectiveness of a PUPP in reducing injury to patients, implementation of these programs can affect facility reimbursement. Noting that hospital-acquired conditions could be reasonably prevented with evidence-based guidelines, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) discontinued additional payment to hospitals for pressure ulcers that were not present on admission (POA). Because patients with hospital-acquired pressure ulcers tend to have a longer length of stay (12–14 days), reimbursement for hospital care may be further compromised. Checklist 8-1 provides the indicators for Stage III or IV pressure ulcers POA. The WOCN Society (2008) has published a useful guidance document to assist with interpreting the POA rule. The document clarifies the role of the WOC nurse, coder, and physician in determining whether the pressure ulcer is POA and what code to assign. For example, a suspected deep tissue injury (sDTI) is coded as an unstageable pressure ulcer. The POA rule emphasizes the importance of the PUPP component of skin inspection upon admission to any health care facility to establish a baseline for the patient so that subsequent pressure-related abnormalities in the skin can be identified.

CHECKLIST 8-1 Indicators for Stage III to IV Pressure Ulcers POA

✓ Present at time the order for inpatient admission occurs. Pressure ulcer that developed during an outpatient encounter, including the emergency department, observation, or outpatient surgery, is considered POA.

✓ Pressure ulcer diagnosis documented by “provider.” A provider is a physician or any qualified health care practitioner who is legally accountable for establishing the patient’s diagnosis.

✓ Determination of whether the pressure ulcer was POA is based on the provider’s best clinical judgment anytime during the hospital stay.

✓ Inconsistent, missing, or conflicting documentation issues are resolved by the physician.

✓ Pressure ulcer is POA when the patient is discharged with a facility-acquired pressure ulcer and later readmitted with a different diagnosis.

Adapted from Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses (WOCN) Society: Inpatient prospective payment changes: a guide for the WOC nurse, 2008, available at http://www.wocn.org/About_Us/News/30/, accessed August 17, 2010.

Ability to identify the unavoidable pressure ulcer

By stating “hospital-acquired conditions (such as pressure ulcers) could be reasonably prevented with evidence-based guidelines,” the CMS introduces the possibility that some pressure ulcers cannot be avoided. The paucity of evidence of the ability to bring the incidence of pressure ulcers to zero despite extensive prevention interventions further challenges the long-held belief that all pressure ulcers are preventable (Thomas, 2003). When Hagisawa and Barbenel (1999) reported 4.4% as the lowest incidence of pressure ulcers in severely ill patients despite receiving comprehensive and extensive pressure ulcer prevention care, they suggested the concept of a “limit of prevention.” This idea supports the argument that not all pressure ulcers are avoidable even with risk assessment and appropriate preventive interventions.

Prior to the introduction of POA for hospitals, CMS defined the term unavoidable pressure ulcer (for the long-term care setting) as a pressure ulcer that develops in spite of the facility’s best efforts at prevention (Checklist 8-2). However, a similar definition by the CMS for the hospital or home care setting does not exist. The WOCN Society recognized the absence of a definition for acute care as a potential problem. To fill this gap, the WOCN Society released a position statement (Avoidable versus Unavoidable Pressure Ulcers) using the CMS definition of an unavoidable pressure ulcer and refuting the assumption that all pressure ulcers are preventable (WOCN Society, 2009).

CHECKLIST 8-2 Avoidable and Unavoidable Pressure Ulcers

Avoidable

The resident developed a pressure ulcer and the facility did not do one or more of the following:

Unavoidable

The resident developed a pressure ulcer even though the facility did the following:

A PUPP is based on evidence-based guidelines or best practice and therefore provides a structure in which unavoidable pressure ulcers may be identified. Identifying a potentially unavoidable pressure ulcer may not assist with reimbursement in hospitals. However, it will help to identify whether best practice was delivered and therefore may be useful in protecting against litigation. In addition, this definition of avoidable and unavoidable is useful in the population of patients at end of life who may develop a pressure ulcer. While there is support for the concept of skin failure (NPUAP, 2010) as end of life is near, there is no definitive confirmation that this concept is real. For now, the current definition of avoidable and unavoidable pressure ulcers allows for the possibility that a patient at the end of life could develop a pressure ulcer despite appropriate care. However, this definition also protects the patient from the assumption that all pressure ulcers at the end of life are unavoidable. Under the current definition, documentation is the only way to determine if a pressure ulcer was or was not avoidable. See Checklist 8-3 for examples of relevant audit questions for the patient’s medical record.

CHECKLIST 8-3 Pressure Ulcer Prevention Best Practice Audit

✓ Pressure ulcer risk assessment was documented on admission and daily.

✓ Skin inspection was documented on admission and daily.

✓ Removal of devices, such as stockings and splints, at least twice a day was documented.

✓ Devices that cannot be removed, such as indwelling tubes and drains, are stabilized and repositioned for daily skin inspection.

✓ Documented care plan linked risk assessment findings to specific preventive interventions.

✓ Patients with impaired sensory perception, mobility, and activity as defined by the risk assessment scale had the following applicable interventions documented:

✓ Patients with friction/shear risk as defined by the Braden scale had head of bed elevated ≤30 degrees documented (if medically contraindicated, physician’s order and alternative plan to prevent shear injury were documented).

✓ Patients with nutritional deficits as defined by the Braden scale were followed by dietary services once the deficit was identified.

✓ Patients with incontinence have documentation that perineal cleanser and barrier were used and the underlying cause addressed.

✓ Patient/family skin safety education and patient response were documented.

✓ Standard skin safety interventions that were determined to be medically contraindicated or inconsistent with the patient’s overall goals were documented or ordered by a physician and reevaluated routinely.

✓ Inability to adhere to standard skin safety interventions (i.e., noncompliance) was documented with evidence of patient/family education and ongoing efforts to reeducate or modify care plan.

Components of a pupp

A PUPP consists of a best practice bundle and infrastructure (operations). The components of a PUPP have been widely adopted by WOC nurses for years (Bryant et al, 1992) and were included in the 1992 AHCPR Pressure Ulcers Prevention Guideline. Historically, PUPPs have been demonstrated to be effective at reducing the incidence of pressure ulcers. However, the implementation, maintenance, and survival of the PUPP was often dependent on WOC nurse involvement. While the successful PUPP may be coordinated by the wound specialist, it should not be owned or dependent on one individual or group. Rather, it must be adopted into the facility’s overall patient safety culture of the facility, supported and protected by administration, and therefore integrated into the facility’s infrastructure.

Establishing a best practice bundle

Skin inspection and assessment

A skin inspection should be obtained for all patients upon admission. Because the admission inspection serves as a baseline for comparisons and pressure ulcers can develop quickly, this skin inspection should be obtained as soon as possible. Although the exact time frame for obtaining a skin inspection is not specified in the literature, physiologically a pressure can develop as soon as one hour (Gefen, 2008). Therefore, it may be reasonable to inspect the skin within the first few hours of admission given the need for patient repositioning and other cares that are conducive for skin inspection (see Table 6-1). Subsequent inspection and monitoring by trained staff is recommended at least daily for patients at risk for pressure ulcers or who have impaired skin integrity (NPUAP and EPUAP, 2009). Deviations from normal should be compared with the adjacent skin or contralateral body part and documented. Optimal visualization and palpation of skin changes require adequate lighting, removal of garments, repositioning of medical devices, and the spreading of skin folds, buttocks, and toes. Unlike inspection, skin assessment involves interpretation and synthesis of additional data gathered from the comprehensive holistic patient assessment such as nutrition, perfusion, medications, and other comorbidities. Chapter 6 presents a detailed discussion related to skin assessment, inspection, and monitoring, including considerations for darkly pigmented skin (see Checklist 6-1).

Risk assessment and screening

Chapter 7 presents a theoretical framework of pressure ulcer development and a description of intrinsic and extrinsic factors that place a patient at risk for pressure ulcer development (Figure 7-2). As with other assessments, pressure ulcer risk assessment includes identification of subjective, objective, and psychosocial factors to determine and assess the risk and care needs of the patient (Stechmiller et al, 2008). Many of these risk factors at first glance seem intuitive. However, due to highly variable experiences and knowledge among caregivers, the accuracy of clinical judgment and intuitive sense in identifying those at risk is not reliable (Bolton, 2007; Pancorbo-Hidalgo et al, 2006). Furthermore, the assumption that all patients are at risk and that preventive measures should be universally applied is difficult to defend due to the inefficient use of resources. Therefore, to enhance the accuracy of pressure ulcer risk assessment a validated risk screening scale must be inluded (NPUAP and EPUAP, 2009; WOCN Society 2003, 2010; Stechmiller et al, 2008).

A risk scale is a noninvasive, cost-effective method for distinguishing between patients who are at risk for developing a pressure ulcer from those who are not. Scales identify the extent to which a person exhibits a specific risk factor, thus directing the selection of interventions needed (Braden, 2010). In selecting a scale for predicting a condition such as a pressure ulcer, the scale must have demonstrated reliability and validity. Reliability refers to the degree to which the results obtained by the measurement procedure can be replicated. For example, if two nurses administered a pressure ulcer risk scale on the same patient at the same time and their scores were the same, the reliability of the scale would be a perfect 1.0, or 100% agreement. Validity refers to accuracy. A screening test such as a pressure ulcer risk scale should provide a good preliminary test of which individuals actually are at risk and which are not. Validity has two components: sensitivity, which correctly identifies patients at risk, and specificity, which correctly identifies patients not at risk. An ideal risk scale would be 100% sensitive and 100% specific, so it does not overpredict (therefore no false-positive scores) or underpredict (no false-negative scores). However, 100% is rarely achieved due to an inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity; as the scale becomes more sensitive, specificity declines. Nevertheless, these measures of predictability are invaluable when comparing tools that attempt to predict a condition such as pressure ulcer.

The validity and reliability of several pressure ulcer risk assessment scales have been reported in the literature and summarized in a synthesis and systematic review (Bolton, 2007; Pancorbo-Hidalgo, 2006). Recommendations related to pressure ulcer risk assessment, such as frequency, who should administer, and which patients should be assessed, are summarized in Box 8-1 (see Appendix B for examples of risk assessment scales).

BOX 8-1 Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scales: Summary of Recommendations

• Pressure ulcer risk assessment scales should be administered to all patients with one or more risk factors for pressure ulcer development when admitted to a hospital’s medical, surgical, intensive care, orthopedic, cardiovascular, or step-down unit, home care, hospice, or extended care facility (Bolton, 2007).

• The Braden scale (Table 8-1) then the Norton and Waterloo scales (Appendix B) have strongest body of evidence supporting validity and reliability (Bolton, 2007).

• Pressure ulcer risk assessment scales should be administered by professional nurse (Bolton, 2007).

• Braden and Norton scales have demonstrated interrater reliability when administered by both registered nurses and licensed practical nurses (Bolton, 2007).

• Risk assessment is not valid and reliable unless those administering the assessment have access to the complete scale and subscale descriptors (Bolton, 2007).

Using the braden scale.

One of the most widely used and researched pressure ulcer risk tools is the Braden Scale for the Prediction of Pressure Ulcer Risk (Stechmiller et al, 2008). Translated into many languages, numerous reports attest to the reliability (0.83–0.95) of the scale with adequately trained registered nurses and licensed practical nurses (Magnan and Maklebust, 2008, 2009). Following meta-analysis, specificity and sensitivity of the Braden scale are reported to be 68% and 57%, respectively. In the same analysis, the percent correctly classified was reported as 67%, the positive predictive value was 23%, and the negative predictive value was 91% (Bolton, 2007).

The Braden scale is composed of six risk factor subscales that conceptually reflect degrees of sensory perception, skin moisture, physical activity, nutritional intake, friction and shear, and ability to change and control body position. All subscales are rated from 1 (most risk) to 4 (least risk), except for the friction and shear subscale, which is rated from 1 to 3. Each rating is accompanied by a brief description of criteria for assigning the rating. Therefore the subscales identify which risk factors are present so that interventions can be targeted to reduce specific risk factors (Table 8-2) (WOCN Society, 2010).

TABLE 8-2 Skin Safety Interventions by Risk Factor

Potential total scores range from 4 to 23. Based on research in three types of settings, the critical cutoff score has been set at 18. A score of 18 results in higher overprediction but decreases the number of false-negative results (Bergstrom et al, 1998). Braden scale scores can be grouped according to level of risk: not at risk (>18), mild risk (15–18), moderate risk (13–14), high risk (10–12), and very high risk (≤9) (Ayello and Braden, 2002). When a patient has a pressure ulcer or a history of a pressure ulcer but is rated “not at risk” according to the Braden scale, it is recommended to automatically place the patient in the “at-risk” category (Maklebust et al, 2005). Likewise, the level of risk should be increased for any patient whose Braden score indicates he or she is “at risk” and who also has a fever, diastolic blood pressure less than 60, or low albumin/prealbumin (WOCN Society, 2010). For example, a patient with a Braden score of 12 would be considered at moderate risk but should be “upgraded” to the high-risk category if he or she also has a fever.

Accurate use of the Braden scale requires user training and retraining, even when nurses use the tool regularly and for a long period of time. A study involving more than 2,500 nurses in Detroit Medical Center showed that only 75.5% of nurses correctly rated Braden scale levels (Maklebust et al, 2005). Although the two extremes of risk levels, “not at risk” and “severe risk,” were most often rated correctly, the subscales “moisture” and “sensory perception” were most often misunderstood. Therefore annual competencies for risk assessment are justified (Magnan and Maklebust, 2008; Maklebust et al, 2005). Similarly, the definitions for risk factors and subscales for each risk factor are essential in both paper or electronic documentation systems. The following section discusses the Braden subscales and measurement of risk factors.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree