CHAPTER 8 Dermatological assessment

Introduction

Dermatology is the study of the skin and its disorders. More than just an inert barrier, the integument is a highly active organ with an important role in physiology and homeostasis. There are over 5000 recognised skin disorders in existence but the largest percentage of skin disease is due to a handful of conditions, which may range from the trivial (i.e. minor bruising) to life-threatening (i.e. malignant melanoma). Most skin diseases do not have a significant mortality, although they cause significant morbidity and have a substantial effect on the quality of life of patients (Harlow et al 1998). Typically, skin disorders affect individuals in a number of ways (the four Ds):

Approach to the patient

Psychological aspects of skin disease

The skin defines who we are and how we are perceived to be. It is on our appearance we are judged by others (Lawton 2000). One only has to see the amount of time and money invested in changing or enhancing our appearance to appreciate how important the skin and its appendages are. A common mistake of students when faced with a patient with widespread skin disease is to remain at a distance, avoiding any physical contact. Skin diseases are subconsciously often perceived as nasty, dirty or infectious.

As a practitioner, preconceptions need to be overcome if the patient is to be reassured that they are in the care of an empathetic, understanding professional. It should be remembered that the problems of the skin patient may be more than skin deep, even with conditions that are perceived by the practitioner to be trivial. Many patients with most common skin disorders, such as psoriasis and eczema, have a quality of life that is similar to the quality of life of patients with other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, cancer and heart disease. Often, the extent of the skin disease is not correlated with the sufferer’s well-being (Jayaprakasam et al 2002) and many conditions may be aggravated by psychological stress, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and lichen planus. It should also be borne in mind that often just acknowledgement and discussion of the wider problems with a patient, in a sensitive and empathetic manner, is an important aspect of the assessment.

The purpose of assessment

How common is skin disease?

Reliable data are difficult to obtain but skin disorders are thought to affect around a quarter of the population, with only a small percentage seeking professional help. Typically, 10–20% of a general practitioner’s annual workload involves skin disorders (Office of Population Census and Surveys 1991–1992), and podiatrists also spend a significant amount of time treating skin conditions (e.g. hyperkeratosis, nail disorders and wounds). The most common disorders that affect the lower limb (Gawkrodger 2002) are:

Skin structure and function

The skin (or integument) is the largest organ system and covers around 1.8 m2. The skin is much more than just an inert wrapping, it is a highly active organ that fulfils many functions (Table 8.1) which are determined by its structure. The skin comprises three layers: an epithelium (epidermis) and a connective tissue matrix (the dermis) firmly bound together at the dermo-epidermal junction (Fig. 8.1); below the dermis lies the subcutaneous (fat) layer.

Table 8.1 Functions of the skin

| Function | Specific property |

|---|---|

| Barrier properties | |

| Sense organ | Touch/vibration/pressure/temperature Nociception |

| Other |

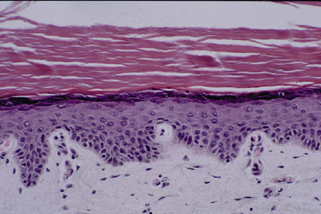

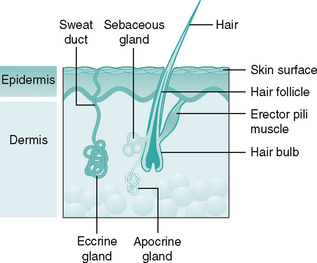

Figure 8.1 Normal skin (not to scale) showing epidermis and dermis and the skin appendages, excluding nail.

Epidermis

The epidermis (Fig. 8.2) is an avascular structure, relying on the diffusion of materials across the dermo-epidermal junction for nutrients and waste disposal. It is principally composed of keratinocytes (corneocytes), which make up approximately 80% of the cells, as well as melanocytes, Merkel’s discs and Langerhans’ cells. Appendages of the epidermis include the nails, sweat glands and sebaceous glands (Fig. 8.1).

Basal layer (stratum germinativum)

For the most part, the basal layer consists of a single, undulating layer of cuboidal keratinocytes. The cells within this layer are firmly attached to the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ) by tonofilaments which arise from the cytoplasm of the cells linking into the hemidesmosomes anchored into the DEJ (Venning 2000). These mitotically active cells generate the cells of the more superficial layers of the epidermis.

Scattered throughout this layer are specialist cells known as melanocytes. In sun-exposed areas (e.g. the face) they may have a ratio of 1 in 4, whereas on unexposed areas such as the plantar surface of the foot their numbers may decrease to 1 in 30. These cells are well developed in the epidermis of humans as we have a relatively hairless integument. Melanocytes are dendritic cells which produce the pigment melanin in specialist organelles known as melanosomes. These melanin granules then pass along the dendritic processes of the cell and are distributed evenly to adjacent keratinocytes. The melanin forms a protective cap over the cell nucleus, its function being to limit the amount of harmful ultraviolet radiation reaching the DNA within the nucleus. In addition, melanin and its hormonal pathways has a wider role in modulating inflammation within the skin (Eves et al 2006). The amount of melanin produced across various races is roughly equal; however, in darker skins the melanin granules are much more dense and less susceptible to degradation as they ascend through the epidermis.

Merkel’s cells are specialised nerve endings of unknown origin, possibly a modified keratinocyte (McKee 1996) found in the basal layer. Their function is thought to be the perception of light touch. They are typically only found in specific regions of the skin, being numerous on the volar (pulp) surfaces of the fingers and toes, in the nail beds and the dorsum of the foot.

Prickle cell layer (stratum spinosum)

The new cells generated by the active basal layer pass into the stratum spinosum. Here they become more polyhedral in shape. Internally, large numbers of keratin filaments (tonofilaments) surround the nucleus, whereas externally the cells have abundant spinous processes. These are desmosomes, bonding adjacent cells together, and are an important component of the epidermis, as they resist mechanical stress. In the upper part of this layer are the first lamellar granules. These secretory organelles contain many substances such as glycoproteins, phospholipids, sterols and lipases. The granules are responsible for the barrier function found higher in the epidermis (Ishida-Yamamoto et al 2007).

Granular layer (stratum granulosum)

By the time the ascending cells have reached the granular layer they are much more flattened in appearance and are packed with keratohyalin granules. These granules are primarily composed of proteins and various types of keratins. As the cells move up towards the next layer of the epidermis the lamellar granules migrate to and fuse with the cell membrane, expelling their contents into the intercellular space. The ejected lipid material is then organised into sheets at the junction with the stratum corneum. This forms a hydrophobic barrier (an almost watertight seal) along the junction of the two layers. In eczematous plaques, this process of extrusion is often reduced, leading to increased water loss through the epidermis and resultant fissuring (Cork 1997).

Horny layer (stratum corneum)

As the cell becomes cornified it loses a percentage of its water content and has a very flattened appearance with around 15–20 layers of keratinocytes. The remaining intracellular water accumulates, acting as a plasticiser with intracellular keratin, and causes the cell to swell. This improves the barrier seal to the epidermis and prevents fissuring of the skin under normal tensile forces (Cork 1997). Cells at this level begin the little understood pre-programmed cell death with most of the intracellular material undergoing breakdown, leaving just the keratin and protein matrix within these now cornified cells.

Dermo-epidermal junction

The dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ) is the point at which the dermis meets the epidermis. The DEJ is a basement membrane divided into a number of layers, crossed by a complex of filaments, keratins and proteins that form an anchoring surface between the dermis and epidermis. In areas of greater mechanical stress, to enhance adhesion the dermis makes regular finger-like folds into the overlying epidermis, known as dermal papillae. These are complemented by protrusions from the epidermis into the dermis, known as rete pegs or epidermal ridges. This undulation serves to increase the surface area of attachment and is a major feature of the plantar surface of the foot, where mechanical stresses can be high. Pathologically, the DEJ is the site of many pathologies and this can lead to loss of adhesion and the development of blistering diseases (e.g. epidermolysis bullosa, dermatitis herpetiformis).

Dermis

Blood supply and lymphatics

From the papillary plexus, single capillaries loop upwards into the dermal papillae. These tiny vessels loop and descend to drain into venules within the papillary plexus and then descend further into the deeper dermis, eventually reconnecting with the subcutaneous blood vessels. Within the foot, the sole contains the most densely organised network of capillaries in the skin (Pasyk et al 1989), which correlates well with the thickness of the overlying epidermis. It has no thermoregulatory role.

Lymph vessels are found throughout the dermis. Within the papillary dermis, highly distensible lymphatic end bulbs drain intercellular fluids and smaller particles. These empty into larger vessels, which descend to the lymphatics in the subcutaneous layer. Ryan (1995) suggests that their function is key to maintaining turgidity, which is vital to retain mechanical resilience in the skin, requiring a fine balance between supply and drainage, as dehydration and oedema can lead to a reduction in skin stiffness and deformation in the structure of collagen and elastic fibres.

Skin appendages

Sweat glands

Sweat glands exist in two forms. The larger apocrine glands are exclusively associated with the hair follicle in the groin and axillae, whereas the smaller eccrine gland is a simple coiled structure located in the reticular dermis with an opening directly onto the epidermis. Stimulated primarily by the sympathetic branch of the autonomic system, sweat glands are an important mechanism for thermoregulation, mainly above waist level (Ryan 1995). They are most numerous on the palms and soles. Under normal circumstances a small, steady flow of sweat is produced, which is thought to aid grip. This function is further enhanced on the palms and soles by the presence of dermatoglyphics. These skin creases, present at birth, are a result of the unique arrangement of collagen fibres in the dermis and are more prominent on the weightbearing surfaces of the foot (pulp of the toes, heel and metatarsal area) and palmar area (fingerprints). Not only do they act like the tread on a tyre in conjunction with the small amounts of sweat, but within these areas, there is a dense and highly organised neural network in the underlying dermis (Montagna 1960) which provides a rich tactile perception necessary to protect the integrity of the foot.

History and examination of the skin

Dermatological assessment consists of three parts:

History taking

Occupation

Many occupations expose the skin to irritants and allergens. A patient may need to wear a particular garment or item of footwear as part of their job and that may be causing the problem. It may be that other members of the workforce are similarly affected. Outdoor workers or workers who are exposed to wet or cold will also have problems particular to them; for instance, skin cancer is higher in those with outdoor occupations.

Clinical examination

• General distribution (localised, widespread or regional)

• Individual lesion morphology

• Assessment of other structures

General distribution

When a widespread eruption is suspected, it is important to look and ask about all of the skin. Patients may often be reluctant to discuss other areas or simply not connect them to the current condition. For example, scalp psoriasis can mimic dandruff. A patient concerned with scaly plaques on the knees may not connect the two, particularly if they have had dandruff for some time. Many disorders have a typical pattern or predilection for specific sites, although it should be remembered that patterns could occasionally vary from the norm. Eczema has a common pattern – affecting the flexor surfaces of the arms and legs along with the face. Symmetry of the eruption should also be recorded as this usually denotes an endogenous condition. Table 8.2 gives examples of the distribution patterns of various dermatoses.

Table 8.2 Common patterns of skin disorders

| Condition | Typical distribution pattern |

|---|---|

| Atopic eczema | Antecubital and popliteal fossa, face, neck, hands |

| Contact dermatitis | Hands, face, feet |

| Psoriasis | Extensor surfaces of knees and elbows, scalp, back, nails |

| Lichen planus | Flexor surfaces of wrist, ankles, oral cavity, genitalia |

| Erythema nodosum | Anterior surfaces of shins |

Individual lesion morphology

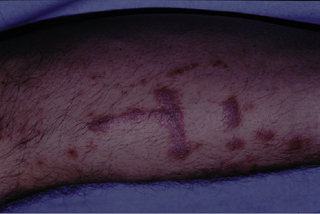

Individual lesions should be assessed. A magnifying glass is useful along with good lighting. Initially it is important, if there is more than one lesion, to describe the arrangement (Fig. 8.3). This can include:

• annular (ring-like), e.g. psoriasis, lichen planus, granuloma annulare

• nummular (round, coin-like), e.g. nummular eczema

• discoid (disc-like), e.g. eczema, psoriasis

• reticulate (net-like), i.e. livedo reticularis

• arcuate (curved), e.g. contact dermatitis

• grouped, e.g. insect bites, dermatitis herpetiformis

• Koebner’s phenomenon, e.g. warts, psoriasis (Fig. 8.4), lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum.

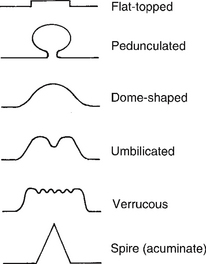

Note that some disorders may have several configurations. Koebner’s phenomenon is when skin lesions of a specific disease appear following trauma at a site which was previously unaffected. The edge of the lesion should also be inspected. Is it discrete or ill-defined? For example, psoriasis and fungal infections have much more marked, well-defined edges than eczema. Surface contour should also be noted (Fig. 8.5).

Touch

It is possible to determine surface changes in texture and whether the skin disease relates only to the surface of the skin or whether it relates to the structures beneath. Light touch is required to perceive superficial changes (i.e. texture of a surface lesion), whereas progressively deeper pressure will reflect changes to the lower structures in the dermis and subcutaneous layers. Oedema feels flocculent under the fingers. Typical surface changes include a soft moist texture due to excessive sweating or a dry and roughened texture due to a lack of sweating, that is anhidrosis. Deeper lesions may be described as hard, nodular, mobile, soft, etc.

Odour

When examining individual lesions, clear descriptions using well-recognised terms are essential. This allows good communication between health professionals. In dermatology, there are many descriptive terms: some obvious, others less so. Familiarity with this terminology will ensure good inter-professional communication. Skin lesions can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary lesions arise due to the initial effects of a condition; secondary lesions evolve from or as a complication of primary lesions. The distinction between primary and secondary is not always clear; some lesions can be classed as primary or secondary (Tables 8.3, 8.4). Some of the more common terms used in assessing the surface of the skin are described below.

Table 8.3 Primary skin lesions

| Term | Description and example |

|---|---|

| Erythema | Redness, often due to inflammatory response |

| Macule | Flat, differently coloured, e.g. freckles, vitiligo |

| Papule | Palpable, solid bump in skin, e.g. lichen planus |

| Nodule | Palpable, deeper mass than a papule, e.g. ganglion, rheumatoid nodule |

| Plaque | Elevated, disc-shaped area of skin over 1 cm in diameter, e.g. psoriasis |

| Tumour | Large mass over 2 cm in diameter, e.g. lipoma |

| Cyst | Subdermal, fluid-filled fibrous swelling, loosely attached to deeper structures, e.g. dermal cyst |

| Weal | Large oedematous bump, e.g. insect bite |

| Vesicle | Tiny, pinprick-sized collection of fluid, e.g. mycosis, pompholyx |

| Bulla | Serous fluid/blood-filled intraepidermal or dermoepidermal sac, e.g. bullous pemphigoid |

| Pustule | Vesicle or bulla filled with pus, e.g. acne, pustular psoriasis |

| Burrow | Short, linear mark in skin visible with magnifying lens, e.g. scabies |

| Ecchymosis | Large extravasation of blood into the tissues, i.e. bruising |

| Petechia | Pinhead-sized macule caused by blood seeping into skin |

| Telangiectasia | Permanently dilated small cutaneous blood vessels |

Table 8.4 Secondary skin lesions

| Term | Description and example |

|---|---|

| Scale | Flake of skin, e.g. mycosis, psoriasis |

| Crust | Scab, dried serous exudates, e.g. acute eczema |

| Excoriation | Scratch marks, e.g. pruritus |

| Fissure | Crack in dry or moist skin |

| Necrosis | Non-viable tissue |

| Ulcer | Loss of epidermis; may extend through the dermis to deeper tissue, e.g. venous ulcer |

| Scar | Fibrous tissue production post-healing |

| Keloid | Excessive production of fibrous tissue post-healing |

| Striae | Lines in skin that do not have normal skin tone, e.g. striae tensa in pregnancy, Cushing’s disease |

| Purpura | Purplish lesions which do not blanche under pressure, e.g. vitamin C deficiency |

| Urticaria | ‘Nettle rash’, e.g. drug eruption, allergy, heat |

| Lichenification | Patchy ‘toughening’ of skin, e.g. chronic eczema |

| Haematoma | Blood-filled blister |

| Sinus | Channel that allows the escape of pus or fluid from tissues |

Scaly

Normally the skin sheds skin cells individually or in small clumps. This is imperceptible to the eye. If the skin is weathered or diseased, skin shedding becomes abnormal, the clumps of skin become larger and appear as flakes or scales. These scales may be small, as in the dryness (xerosis) of atopic eczema, or large, as in ichthyosis. Scratching the surface of skin is helpful as it accentuates scaling and may help with diagnosis. Psoriasis will demonstrate pinpoint bleeding when scratched and the scaling will become more pronounced (Auspitz’s sign).

Excoriations, erosions and ulcers

Excoriation means scratch and is usually a feature of itching or, less commonly, pain. It may represent underlying skin pathology such as scabies or eczema or indicate disease elsewhere, e.g. renal or hepatic failure. Erosions are partial-thickness breaks in the surface of the skin caused by physical injury including excoriation or where blisters have broken. An ulcer is an area of full-thickness skin loss, usually covered by exudate or crust.

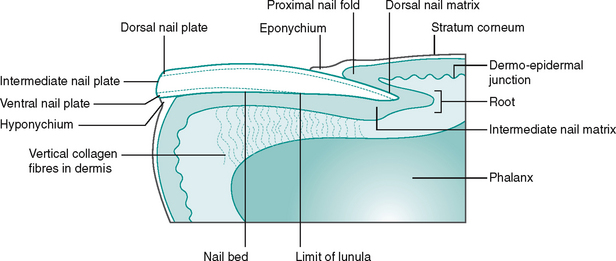

Assessment of the nail

The nails should be inspected as part of the main dermatological assessment. The nail has evolved as a rigid structure to improve dexterity but in the foot the nail is purely a protective plate overlying the deeper structures and acting as a counter pressure to the volar tissues (Baran et al 2003). The nail unit (Fig. 8.6) is well provided with a rich neurovascular supply and, as a result, is sensitive to internal changes, often manifesting these subtle changes in the nail structure. External factors too, such as trauma, can modify nail shape. Therefore, a proper footwear assessment should be undertaken, to complete the clinical picture, when looking for reasons for changes in nail shape, colour, etc. A glossary of the main terms used to describe nail changes can be found in Table 8.5.

Table 8.5 Glossary of nail conditions

| Condition | Definition |

|---|---|

| Onychauxis | Thickening of the nail plate, usually due to trauma |

| Onychogryphosis | Thickened nail with a distortion in the direction of growth |

| Onycholysis | Separation of the nail from the nail bed, distal to proximal |

| Onychomadesis | Separation of the nail from the nail bed, proximal to distal |

| Onychocryptosis | Ingrowing toe nail |

| Involution | An inward curvature of the lateral or medial edges of the nail plate, towards the nail bed |

| Splinter haemorrhage | Longitudinal, plum-coloured linear haemorrhages (around 2 mm in length) under the nail plate |

| Paronychia | Inflammation of the tissues surrounding the nails |

| Onychomycosis | Fungal infection of the nail plate |

| Chromonychia | Abnormal coloration of the nail tissue |

| Koilonychia | Transverse and longitudinal concave nail dystrophy which gives a spoon-shaped appearance |

| Clubbing | Increased longitudinal curvature of the nail plate with enlargement of the pulp of the digit |

| Beau’s lines | Transverse ridging of the nail plate seen as the result of a temporary cessation of nail growth |

Key aspects of examination include assessment of the following factors.

Rate of nail growth

There is great variation between individuals in the rate of nail growth. The average rate for a finger nail is 0.1 mm/day (or 3 mm/month), whereas toe nails grow at a half to a third of this rate (Zaias 1980). Consequently, a normal finger nail will grow completely in about 6 months, whereas a toe nail will take 12–18 months. Such information is useful to determine the approximate time of events, for example the time of trauma to a nail, the likely clearance time of a haematoma. Most systemic disorders lead to a decline in the rate of nail growth but a few may have the opposite effect (psoriasis, hyperthyroidism, nail trauma and drugs).

Shape of the nail plate

The breadth of the nail matrix and length of the nail bed normally dictate the shape of the nail plate (finger nails being rectangular and toe nails, quadrangular). The contour of the underlying phalanx, and toe position, may modify this. The most commonly occurring nail shape alteration in the toe nail is transverse over-curvature or involution (pincer nail). This is typically seen in the nail plate of the hallux and is often accompanied by pain when direct pressure is applied to the nail. If there is an underlying subungual exostosis (Fig. 8.7), lifting of the distal nail plate occurs, often accompanied by pain. Frequently seen in young adults, a lateral X-ray will differentiate between this and other causes of painful nails such as onychocryptosis (Fig. 8.8) or abnormal involution of the nail plate sometimes referred to as pincer nail (Fig. 8.9). Internal causes of nail shape alterations include koilonychia (spooning) and clubbing, and their causes are listed in Table 8.6.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree