Dermatologic Conditions in Athletes

Delmas J. Bolin

During the course of training and competition, athletes develop numerous skin conditions that are directly related to sports participation. The team physician must appropriately recognize and treat these conditions both in the training room and on the field. Skin problems in athletes generally arise from mechanical, environmental, and infectious causes. The age, skin type, and sex of the athlete influence susceptibility. The physician must consider the physical demands, required equipment, training environment, and the intensity and amount of training when making management decisions. Some skin injuries are directly attributable to technical faults or equipment.

Skin infections are of much higher concern in high contact sports, such as wrestling, where there is significant risk of epidemic spread. The recent increase in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) requires prompt recognition and treatment. Athletes with MRSA, impetigo, molluscum contagiosum, and herpes can spread the disease to opponents, coaches, and teammates, necessitating precompetition skin checks and specific guidelines for return to play.

The management of skin conditions is made easier when identified early by athletic trainers, athletes, and coaches. In many cases, prompt recognition and intervention can prevent many skin problems associated with athletic activity. Developing a treatment plan and preparing a well-stocked coverage bag and training room are essential to return athletes with skin conditions quickly and safely to optimal performance.

Traumatic Injuries

Lacerations

Skin lacerations during athletic contests must be handled efficiently. Athletes are barred from competition if they are actively bleeding or if they have blood-soiled uniforms. Strict universal precautions should be observed. Often, these wounds can be quickly closed and the athlete returned to competition. Informed consent from the athletes’ parent’s, particularly in the high school setting, is essential.

After adequate anesthesia is established, the wound should be thoroughly cleaned and irrigated with sterile saline to remove loose debris. Lavage should be accomplished with no smaller bore than an 18-gauge needle to avoid “jet injury” to the tissue. Iodine-containing solutions will sterilize the surrounding tissue, but care should be taken not to introduce them directly into the wound as they can hinder tissue healing. Following sterile preparation, the wound can be closed and protectively bandaged. If stitches are required during competition, it may be most efficient to close the wound temporarily with Steri-strips, then definitively close the wound with stitches at halftime or after the competition.

Planning before the event can assist in efficient return to play for the injured athlete (see Table 17.1). The coverage bag should include a variety of syringes and needles as well as small-unit sterile lidocaine or other anesthetic. Closure material including Steri-strips and tincture of benzoin,

suture material, and sterile kits should be available. Acrocyanate “skin glue” is now commonly used and very effective at closing wounds with good cosmetic result (1). The injury must be clean, dry, and free from active bleeding. Thorough cleaning of the wound is essential before closure to prevent infection. After closure, the athlete can return to play. In settings where there is limited time to address injuries during the competition, such as wrestling or tennis, “skin glue” may provide more efficient closure than stitches.

suture material, and sterile kits should be available. Acrocyanate “skin glue” is now commonly used and very effective at closing wounds with good cosmetic result (1). The injury must be clean, dry, and free from active bleeding. Thorough cleaning of the wound is essential before closure to prevent infection. After closure, the athlete can return to play. In settings where there is limited time to address injuries during the competition, such as wrestling or tennis, “skin glue” may provide more efficient closure than stitches.

TABLE 17.1 Suggested Wound Management Supplies for The Medical Coverage Bag | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mechanical Injuries

Familiarity with the demands of sport and its associated equipment is often overlooked in the prevention of skin injuries. For example, Lacrosse players frequently develop bruising from blocking impact by opponent’s crosses. If a player has an injured thigh or shoulder muscle, these areas can be padded to protect them during competition. Familiarity with the required equipment and inspection for improper padding is essential. Unpadded sharp corners may predispose to injury (see Figure 17.1).

Sports participation places the skin at risk primarily through friction and impact, either with the athlete’s own equipment or the playing surface. Shear forces or repetitive impacts can lead to subcutaneous hemorrhages. There are numerous conditions that are sports specific, with similar underlying mechanisms.

Talon noir (literally, black heel) is commonly seen in young adults. It consists of horizontal petechiae usually on the posterior or lateral heel (see Figure 17.2). It is most commonly seen in sports that require frequent stops and starts, such as tennis, racquetball, or basketball. The condition is benign, painless, and resolves spontaneously after the season. Similar lesions can appear on the palms (Tache noir) of gymnasts, golfers, and weight lifters. It can be mistaken for melanoma, leading some to biopsy the site. If definitive diagnosis is necessary, the skin can be scraped, mixed with saline and tested for occult blood (2).

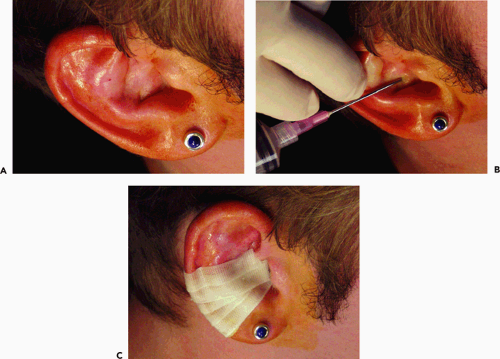

Although not involving the skin per se, shear forces can separate the skin from underlying tissues, resulting in hematoma formation. In wrestling, shear forces secondary to contact of the ear with the mat can separate skin from underlying cartilage and lead to auricular hematoma (see Figure 17.3). Auricular hematomas must be rapidly recognized, drained, and splinted with a compression dressing to prevent the development of a chronic deformity, cauliflower ear.

Jogger’s Nipples are raw, painful, and eroded skin that develops more commonly in male long-distance runners. Friction between the nipple/areolar complex and the shirt fabric during the run results in raw, irritated nipples. Women are usually protected by sports bras. Men can avoid the condition by running without a shirt or by covering the nipples with adhesive bandages or petroleum jelly immediately before running.

There are several other common sports specific conditions that are similar. Golfer’s nails are small subungual splinter hemorrhages that develop from gripping the club too tightly. Proper grip technique prevents the problem (3). Mogul skier’s palms are ecchymoses that are seen over the hypothenar eminence secondary to repetitive trauma. Like tache noir, they clear at the end of the season (4).

Piezogenic papules are small, often painful collections of extruded fat on the lateral aspect of the heels (see Figure 17.4). They are usually flesh colored and may only be noticeable when standing. They are commonly seen in long-distance runners. A heel cup may reduce symptoms (5).

Long-distance runners may develop a small area of ecchymosis in the gluteal cleft, known as “runner’s rump.” It is thought to be secondary to prolonged friction at the site, and reassurance is indicated. Rowers develop gluteal lichen simplex chronicus (“rower’s rump”) from prolonged rowing on unpadded seats. Seat padding lessens friction and resolution is speeded with topical fluorinated steroids (2). A thorough understanding of the demands

of the sport may provide insight into the etiology of the resulting skin lesions.

of the sport may provide insight into the etiology of the resulting skin lesions.

Abrasions may occur secondary to impact with natural or artificial turf or wrestling mats or by rubbing against improperly fit equipment. During the course of the season, chronic exposure to friction can lead to skin changes, hair loss, or callous formation. For example, soccer goalkeepers often lose the hair of their lateral leg in season due to repetitive diving and sliding (friction alopecia).

The goals of treatment are symptom relief, protection to prevent further injury, and prevention of infection. The skin is erythematous and there may be clear serous crusting and weeping. The area should be thoroughly cleansed with soap and water. Protective and antifriction lubricants can protect the skin and provide symptomatic relief. Telfa padding with petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment to reduce friction is often effective.

Blisters from repetitive friction may develop (see Figure 17.5). Common sites are sport-dependent, but are usually on the feet or behind the heels. These usually develop because the athlete has poorly fitting shoes or new shoes at the start of the season. Blisters are typically managed closed, but can be opened and drained if large. Drainage up to three times in the first 24 hours speeds up healing (6). The goal of drainage is to reestablish connection between separated tissue layers. The overlying skin should be left intact to offer protection to the affected area. The practice of injecting blisters with a variety of creams is not supported by the literature as promoting healing and prevents reapproximation of the

injured tissues. Doughnut bandages made from moleskin can protect and relieve pressure. Moleskin doughnuts can lead to localized fluid collection and should be used with caution in dependent locations.

injured tissues. Doughnut bandages made from moleskin can protect and relieve pressure. Moleskin doughnuts can lead to localized fluid collection and should be used with caution in dependent locations.

Figure 17.3 A: Acute on chronic auricular hematoma in a collegiate wrestler. B and C: After drainage, a colloid splint was applied to prevent reaccumulation. |

Athletes should be cautioned about breaking-in new shoes gradually before the start of the season to help prevent calcaneal blisters. Wearing two pairs of socks may prevent blisters, especially if a synthetic fiber is worn against the skin. Synthetic socks wick sweat away from the foot and protect the skin from maceration. Hydrocolloidal antifriction products can be used underneath ankle taping to decrease risk. If infection is a concern, silver sulfadiazine cream can be applied and offers both antifriction and antibiotic protection.

Figure 17.4 Benign piezogenic papules on the instep of a collegiate volleyball player. Papules represent extruded subcutaneous fat and are rarely symptomatic. |

Calluses are secondary to hyperplasia of the epidermis and are the most common dermatosis associated with sports. Callus formation is protective and may actually offer a competitive advantage, as they can permit endurance to repetitive trauma that might otherwise cause blisters or pain (7). In weight lifters, palmar calluses (from gripping the bar) or lichenification on the neck (from resting the bar on the neck during “clean and jerk” technique) are signs of dedication and hours of practice (8). Plantar calluses can be difficult to manage in season for most weight-bearing athletes. If symptomatic, the callus can be gently pared or debrided with a pumice stone. Topical salicylic acid plasters or keratolytic emollients (with lactic acid, urea, or salicylic acid) can be used (7). As with management of warts, discussed later, aggressive paring in season should be avoided as it can induce inflammation and make the athlete more uncomfortable. For plantar keratosis, a pad made

from moleskin or wool can be designed to decrease pressure over the callus and spread the forces to less symptomatic areas of the foot.

from moleskin or wool can be designed to decrease pressure over the callus and spread the forces to less symptomatic areas of the foot.

Corns are focal accumulations of keratin that develop over pressure points and bony prominences. They are most commonly seen on the toes. Thorough evaluation of shoe fit and appropriate padding may prevent recurrence. Large or symptomatic corns may be treated with debridement or keratolytic emollients, as described earlier (7).

Subungual hematomas are described in many sports (jogger’s toe, skier’s toe, hiker’s toe, climber’s toe) and may develop acutely or after prolonged repetitive trauma (see Figure 17.6). Acute traumatic subungual hematoma, resulting from being stepped on by the opponent’s cleat, can be quite painful and limit participation. These can be easily released with a portable cautery unit. A small drain hole is made with cautery through the nail. Once the pressure is released, padding can be applied and the athlete returned to play. Long-standing subungual hematomas require no treatment. The discoloration will grow out with the nail. If multiple shades of pigment are noticed under the nail, or if the discoloration leaches to the proximal nail fold, the lesion should be biopsied to rule out melanoma.

Figure 17.6 Jogger’s nails. Subungual hematoma in the second toe of a runner from repetitive trauma. |

Connective tissue nodules (collagenomas) may develop at sites of repetitive pressure or trauma. These have been described as “surfers nodules” but may be seen in football players or boxers. If the athlete has severe pain, the nodules can be injected with corticosteroid or excised. Often, no treatment is required (9).

Swimmer’s shoulder is usually seen in unshaven male freestyle swimmers. It is an erythematous plaque on the shoulder that occurs secondary to beard friction against the skin. Shaving prevents the problem (10).

Environmental Injuries

Sun Exposure

Because many sports are played outside, chronic exposure to sun may increase the athlete’s risk for long-term complications of sun exposure, including thinning of the skin and skin cancer. Sunburn is the most common sun-related skin disorder. Care should be taken to avoid high intensity sunlight without protection, especially during the period of 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Complications of sunblock use include risk of contact dermatitis from sunscreen additives and slightly increased incidence of folliculitis with oily preparations (11). Some athletes do not like the residue from oily sunblocks; however, the benefits far outweigh the risks. The sports physician should counsel athletes to limit sun exposure as much as possible, especially those with fair complexions who burn easily. As year-round tanning has become trendy, athletes should be counseled to limit exposure in tanning beds as well.

Sunscreens are available that protect against ultraviolet (both UVA and UVB) rays. These should be applied copiously 30 minutes before exercise and repeated after periods of intense sweating or water immersion. Use of water-resistant formula enhances protection. A shirt may be used for protection; however, the effectiveness is decreased as the material becomes wet. Darker materials absorb more photo-energy and are more protective. Sunblock should be used under the clothing (12).

Treatment consists of symptomatic treatment for minor burns. Cool compresses and low-dose topical steroids may be used. Second-degree burns may require systemic corticosteroids as well as topical treatments. The burn can be covered with a nonadherent dressing for protection. The burn should be re-evaluated in 2 to 3 days, as the full extent of injury is often not apparent until 48 to 72 hours after exposure.

There has recently been controversy suggesting that swimmers are at increased risk of skin cancer because of exposure to sun. Epidemiological studies suggest that the greater risk is to swimmers who swim in polluted water, where the skin is exposed to potential carcinogens. The sports physician should counsel young athletes to use appropriate sunblock and avoid swimming in open waters where contamination may be present (12).

Photosensitivity may develop in athletes who are taking one of the several general classes of medications. There are more than 50 medicines that are associated with photodermatitis; the likelihood of a reaction with any one of these drugs is highly variable (13). Photosensitivity may develop with certain soap, deodorant, and perfume additives. The symptoms may be similar to sunburn, but can also include blisters, swelling, and rash. The athlete should be counseled to avoid direct sunlight while taking these medications. If a reaction occurs, the medication should be discontinued. In severe cases, corticosteroids or immunosuppressant therapy may be used. If sun exposure cannot be avoided, alternative appropriate medication, if available, should be considered. Table 17.2 lists several commonly prescribed medicines and additives that are associated with photosensitivity.

TABLE 17.2 Medications, Supplements, and Additives That are Associated with Photodermatitis | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|