Chapter 21. Deformities in children

Crooked children are still referred to orthopaedic surgeons for treatment as they were in Andry’s time, but serious deformity is rare today and the majority of children referred to an orthopaedic children’s clinic have nothing more than a minor abnormality of the lower limbs requiring firm reassurance. Reassurance is not always easy; well-intentioned advice or a careless remark by a respected relative, usually a grandparent, can cause anxiety that is difficult to eradicate.

Before reassuring the parents that all is well, it is important to confirm that no serious abnormality is present and it is therefore essential to understand what is normal and what is not.

Normal milestones

The milestones of normal development are very variable and accurate assessment may need a child development specialist. From an orthopaedic standpoint the most important milestones are those shown in Figure 21.1.

|

| Fig. 21.1 Milestones of development: (a) holds the head up unsupported at 3 months; (b) sits up unaided at 6 months; (c) stands up unaided between 9 and 12 months; (d) walks between 12 and 18 months. |

A paediatric opinion is needed if the child cannot do the following:

1. Sit by the age of 9 months.

2. Pull himself or herself upright by 12 months.

3. Walk by the age of 20 months.

Problems with walking

Not all children learn to walk at the same age and some are not very good at it when they do. Some children walk with an ungainly gait, as do some adults, and some learn to walk by using one leg as a prop at the front while the other pushes forwards from behind. This and other ‘trick’ gaits look bizarre but should correct spontaneously, although pathological and normal gaits can look very similar.

Remember DDH (p. 354)

Before reassuring a patient that a child’s gait is normal, always think of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), particularly if the child is aged between 12 and 18 months (p. 354). If there are any of the following features, assume that the child has a dislocated hip until radiographs prove otherwise:

1. Limbs of unequal length.

2. An asymmetrical range of movement of the hips.

3. Asymmetrical skin creases.

4. A lurching gait.

5. A feeling of instability.

The consequences of missing DDH are very serious and radiographic examination of the pelvis is always justified if there is the slightest doubt about the stability of the hips in a child.

Bow legs and knock knees

Valgus or varus deformities in children are very common but seldom serious. Few children have rickets in this day and age but the herd memory of the disease is still active and bowed legs give very reasonable cause for alarm.

Many babies have varus tibiae at birth, and nappies, which hold the hips in abduction, make the bowing more obvious. The bowing also makes the toes turn slightly inward. If the bowing is very obvious the children are said to have outward-curved tibiae but the borderline between normal and abnormal is very vague.

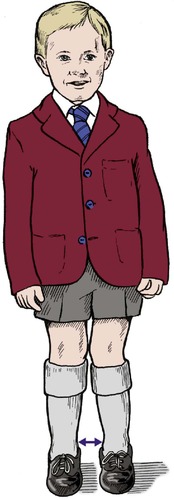

The varus will usually have corrected itself by the age of 3, when it is replaced by a slight valgus deformity at the knee (Fig. 21.2). The amount of valgus deformity is variable but it is permissible to have 10 cm between the ankles at the age of 4 (‘4 inches at 4 years’) when the deformity is at its greatest. A marked improvement can be expected soon after the child starts school at the age of 4 or 5 years.

|

| Fig. 21.2 Normal valgus deformity of the leg. Ten centimetres between the medial malleoli at the age of 4 years will correct spontaneously. |

Before reassuring the parents, it is important to exclude serious disease, of which the following are the most likely under the age of 5:

1. Vitamin D or C deficiency.

2. Blount’s disease, an abnormality of development at the upper end of the tibia which leads to progressive varus deformity.

3. Growth disorders such as epiphyseal injuries and epiphyseal dysplasia.

There are four factors to beware of in children with bow legs and knock knees:

1. More than 10 cm between the malleoli.

2. A family history of skeletal abnormality.

3. Asymmetry.

4. Abnormally short stature.

If one of these features is present there may be a serious developmental abnormality or a dislocated hip. If none then the child will probably develop normally.

In-toe gait

The commonest problem seen in a children’s orthopaedic clinic is an in-toe gait. An in-turned foot is very obvious, the child can fall and the gait attracts much comment.

There are three causes of an in-toe gait:

1. Anteversion of the femoral neck.

2. Metatarsus adductus.

3. Outward curved tibiae.

Anteversion of the femoral neck

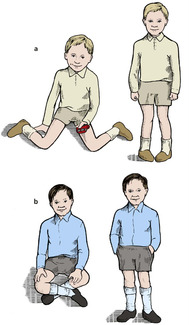

The most common cause is abnormal rotation at the hip due to excessive anteversion of the neck of the femur relative to its shaft. This allows a greater range of internal rotation than external (Fig. 21.3). Abnormalities of rotation are much more obvious with the leg straight than with the hip and knee flexed.

|

| Fig. 21.3 Anteversion and retroversion of the femoral neck: (a) children with anteversion of the femoral neck can sit with their feet out beside them and walk with the toes turned in; (b) children with retroversion can sit with the legs crossed and walk with the toes turned out. |

In an adult, the ranges of internal and external rotation of the hip are roughly the same but in a child there may be 90° of internal rotation and only 30° of external rotation. Such a child will walk with the foot in the middle of the range of motion, i.e. in 30° of internal rotation, and will be able to squat with the legs turned outwards. It is not unusual for one of the parents to recall doing the same thing when young, which makes reassurance easy.

Treatment

No treatment, whether by splintage or operation, is helpful. If the patient has no external rotation at all, a rotational osteotomy of the femur may be required when growth is complete. Apart from this, nothing is needed except firm reassurance that the shape of the femur will gradually change so that the range of internal and external rotation approach each other. The position continues improving until 10 years of age.

Metatarsus adductus

Metatarsus adductus also causes an in-toe gait and is dealt with under foot deformities below.

Outward curved tibiae

Outward curved tibiae can also cause an in-toe gait. No treatment is required.

Out-toe gait

Retroversion of the femoral neck

A smaller number of children have a greater range of external rotation than internal and walk with their feet turned out ‘like Charlie Chaplin’. These children can also sit with their legs crossed, impossible for children with excessive internal rotation. External rotation of the leg is also seen in DDH and this must be excluded before reassuring the parents. As always, check the rest of the child for deformities.

Treatment

As with internal rotation of the hip, firm reassurance is all that is required.

Toe-walkers

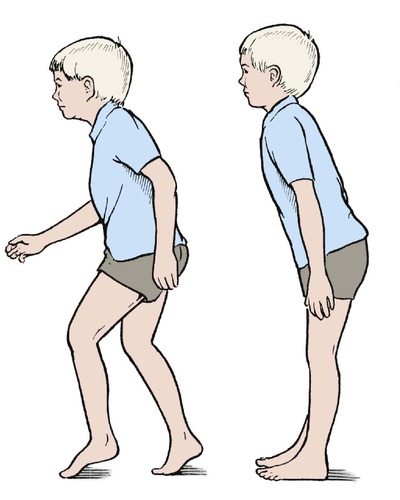

In some children, the Achilles tendon is tight and restricts dorsiflexion of the ankle so that the child walks on tiptoe and cannot stand with the heels flat (Fig. 21.4).

|

| Fig. 21.4 Toe-walkers walk on tiptoe and lean slightly forward when standing. |

The feet and ankles appear normal at first glance and the parents may already have been reassured that ‘there is nothing wrong’ by the time they reach an orthopaedic clinic. On careful examination, dorsiflexion of the ankle is restricted or absent, the child cannot squat with the heels to the ground and stands with a characteristic forward stoop. If they attempt to stand upright, the children fall over backwards. The signs are worse when the child is barefoot.

It must be remembered that hyperactive children and patients with mild cerebral palsy may also walk on their toes. Be sure to exclude neurological abnormalities in toe-walkers!

Treatment

Serial plasters are sometimes effective but lengthening of the Achilles tendon is often required.

Tight hamstrings

If the child has tight hamstrings which prevent forward flexion, suspect spondylolisthesis (p. 457). Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine are essential in any child with tight hamstrings or calf muscles.

Foot deformities

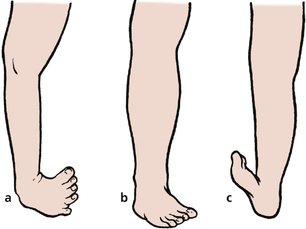

Foot deformities (Fig. 21.5) can be divided into two groups:

1. Forefoot deformities, more common and usually trivial.

2. Hindfoot deformities, less common and more serious.

|

| Fig. 21.5 Foot deformities: (a) talipes equinovarus with a wasted calf; (b) metatarsus adductus; (c) talipes calcaneovalgus. |

Metatarsus adductus

The commonest forefoot deformity is metatarsus adductus or hooked forefoot, which is usually noticed at about the age of 6 months when children begin to pull themselves upright. The deformity occurs at the midtarsal joint (Fig. 21.6a) and the hindfoot is completely normal. This can be confirmed by covering the forefoot while examining the hindfoot. When this is done, the foot looks entirely normal (Fig. 21.6b).

|

| Fig. 21.6 Metatarsus adductus. The deformity arises in the middle of the foot (a). If the forefoot is covered over (b), the foot cannot be distinguished from normal. |

The cause is not known but an attractive suggestion is that the forefoot is pushed inwards by the child while sleeping face down with their bottom in the air, a position only stable if the feet are pointing towards each other. It is certainly true that the condition begins to correct when the child is too ‘bottom-heavy’ to sleep in this position, usually at the age of about 18 months.

Treatment

Treatment begins by reassuring the parents that the child does not have a club foot and that the deformity corrects itself spontaneously in over 90% of patients.

Before the age of 3 years, no active treatment is required apart from gentle stretching of the medial side of the forefoot by holding the heel in one hand and the forefoot in the other. This should be done twice daily when dressing or bathing the child.

After the age of 3, treatment depends on the mobility of the foot. If gentle pressure corrects the deformity completely, observation can be continued, but if it cannot be corrected, serial casts are needed. A below-knee cast is applied in the position of maximum correction and changed at 2 week intervals to achieve a gradual correction. If serial casts are unsuccessful and the deformity is still marked by the age of 6, surgical correction may be necessary.

Congenital talipes equinovarus

The most common type of club foot, congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV), is a deformity of the whole foot, which is pulled downwards (equinus) and inwards (varus) (Fig. 21.7).

|

| Fig. 21.7 Talipes equinovarus in a neonate. |

The condition has been recognized for centuries but remains an enigma. The demi-god Vulcan, who injured his foot when cast from heaven, is depicted with a club foot. The poet Byron also had a club foot.

As far as we know, the condition is caused by failure of growth in the posteromedial muscles of the calf, particularly tibialis posterior, the toe flexors, gastrocnemius and soleus. The muscles are entirely normal in all other respects but are simply too small for the patient. The bones of the forefoot, and sometimes the tibia and fibula, may be shorter than those of the opposite side. The condition is more common if a relative is affected or there is any other genetic abnormality.

Because the muscles on the medial side of the foot and calf are too short, the foot is pulled downwards and inwards with the ankle in flexion. As growth proceeds, the talonavicular joint is distorted, the navicular is pulled off the talus medially and a bony deformity quickly develops as the soft bones of childhood mould themselves to surrounding tissues.

Treatment

No treatment will make the foot and calf completely normal and this should be explained to parents as gently as possible before treatment is begun. It is unkind to lead the parents to believe that a complete cure is possible.

The aims of treatment are twofold:

1. To prevent bony deformity developing.

2. To keep the foot plantigrade; i.e. in such a position that it can be placed flat on the ground.

The Ponseti method of treatment is gaining popularity. This involves sequential gentle manipulation and splinting of the foot with serial casts for a considerable period of time (Fig. 21.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree