Chapter 12 Decongestive Therapy for the Treatment of Lymphedema*

Lymphedema, a disorder characterized by chronic swelling, affects approximately 140 million to 250 million people worldwide. This chapter explores a treatment technique for lymphedema known as complete decongestive therapy (CDT). The components consist of skin and wound care, lymphatic massage, compression, exercise, and patient education. Because of the possible complications associated with lymphedema, this technique should only be performed by or under the direction of a licensed medical professional after a thorough evaluation and plan of care have been established.

Lymphedema is an excessive accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the tissues caused by a transport failure of the lymphatic system and may be acquired through primary or secondary causes. Primary lymphedema is usually caused by a developmental disorder of the lymphatic system. It may manifest in infancy, adolescence, or late adulthood. Primary lymphedema occurs predominantly in females and typically affects either of the lower extremities. It is estimated that approximately 1 in 6000 individuals will acquire primary lymphedema (Dale, 1985).

In developed countries, cancer or its treatment is the most common cause of secondary lymphedema—the result of blockage by the tumor itself, excision of lymph nodes, or radiation therapy. Kissin et al. reported a 25% incidence of lymphedema after mastectomy, rising to 38% in patients treated with axillary lymph node dissection and radiation (Kissin et al., 1986). A comprehensive literature review concluded that the overall incidence of arm edema after mastectomy was 26% with a range from 0% to 56% within 2 years (Erickson et al., 2001). Patients who undergo treatment for cervical, vulvar, and prostate cancer have similar incidences for lymphedema of the lower extremities. The risk increases with an increase in the number of lymph node dissections and radiation therapy (Petereit et al., 1993).

THE LYMPHATIC SYSTEM

Lymphotomes

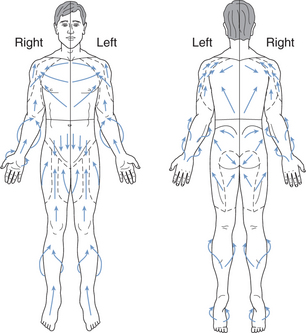

Tissue fluid drainage occurs in distinct regions of the body called lymphotomes. These lymphotomes contain lymph vessels (collectors) that carry lymph fluid along their routes to a common chain of lymph nodes. Lymphotomes are divided by watersheds, narrow anatomical zones where the direction of lymphatic flow changes. There are four lymphotomes of the trunk, which are separated by watersheds in the midsagittal and transverse planes. These are designated right and left thoracic lymphotomes and right and left abdominal lymphotomes. Each of the extremities contains numerous lymphotomes as well. If a particular lymphotome becomes overwhelmed with excess fluid, superficial tissue fluids may cross the watersheds by way of collateral vessels called anastomoses that offer alternate routes of drainage. In this way, excess fluid can be drained into a normally functioning area and decrease the lymphatic load on the involved lymphotome (Figure 12-1).

Lymph Capillaries

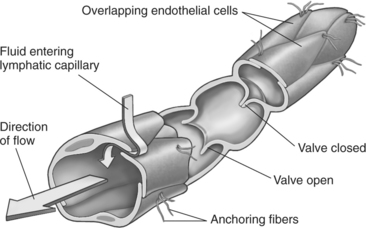

The lymphatic circulation originates with microscopic vessels called lymph capillaries. They are located in most tissues of the body except for the central nervous system, splenic pulp, and bone marrow. The endothelial cells walls of these vessels open and close at the cell junctions to allow the passage of fluids in response to pulse pressure, relaxation and expansion of adjacent arterioles, external compression, and muscle activity. The lymph capillaries contain two sets of valves; the interendothelial junctions prevent the backflow into the interstitium during contraction, and the intralymphatic valves prevent backflow within the lumen during expansion (Figure 12-2).

Collectors

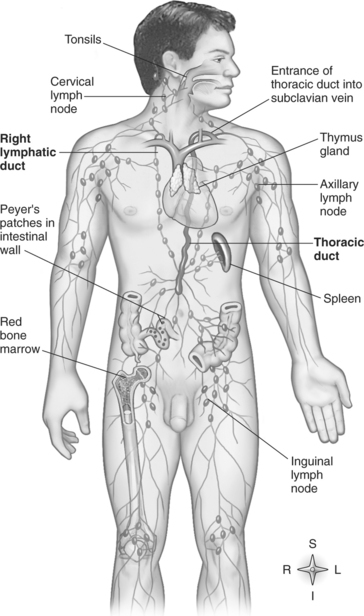

The lymph capillaries combine to form larger afferent collectors located in the subdermal channels. The cell walls of the collectors are muscular and also contain valves to prevent backflow of the lymphatic fluid. The sections between these valves, called lymphangions, contract in response to autonomic sensory input and lymph volume. The afferent collectors eventually lead to lymph nodes where the lymphatic fluid is filtered. The filtered lymphatic fluid then exits the nodes through the efferent collectors. These collectors eventually unite to form larger lymphatic trunks, which finally lead to the main ducts: the thoracic duct or the right lymphatic duct (Figure 12-3).

Trunks

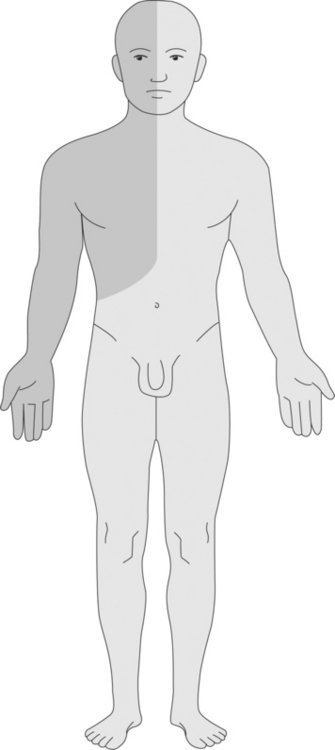

The right lymphatic duct terminates at the juncture of the right internal jugular and right subclavian vein, where the fluid is returned to the vascular system. It is primarily responsible for draining the right thoracic lymphotome and arm and the right side of the face and neck. The thoracic duct originates in the pelvic region at about the level of the second lumbar vertebrae and begins with a large expanse of lymphatic tissue called the cisterna chyli. The thoracic duct receives lymph from the trunks of the lower extremities and the intestinal trunk, and it eventually empties into the juncture of the left internal jugular and subclavian vein. It is responsible for drainage of the gut, the abdominal lymphotomes, the lower extremities, the left thoracic lymphotome, the left arm, and the left side of the face and neck (Figure 12-4 and Figure 12-5).

Figure 12-4 Schematic of lymphatic system.

(From Thibodeau G, Patton K: Anthony’s textbook of anatomy and physiology, ed 17, St. Louis, 2003, Mosby.)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Lymphedema may occur under several conditions:

In addition to the subcutaneous skin changes that occur in chronic lymphedema, the risk of infection increases as a result of the decreased ability to fight infection and the increased concentration of tissue proteins. Multiple bouts of cellulitis can lead to even further degradation of the subcutaneous tissues. The individual’s normal activities may decrease as well, resulting in decreased pumping action of the muscles. This contributes even more to the insufficiency of the lymphatic system. Without treatment to minimize the edema, the patient may begin to experience other complications associated with chronic swelling, such as loss of mobility, joint stiffness, weakness, pain, and poor psychological adjustment (Figure 12-6).

PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT

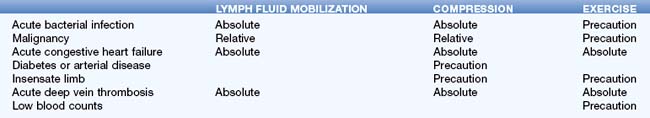

Because of the complexity of the disorder, it is often best to adopt a team approach to management. Members of the team may include a physician, nurse, physical or occupational therapist, the patient, family members, certified garment fitter, nutritionist, and psychologist. Always use sound clinical judgment when initiating treatment, and consult the referring physician when in doubt. Also, be mindful of absolute and relative contraindications and precautions before initiating treatment (Table 12-1). Absolute contraindications indicate that treatment is not appropriate in the presence of certain conditions. Relative contraindications and precautions indicate that treatment may be appropriate in the presence of certain conditions only with proper monitoring and good clinical reasoning. When in doubt, consult the prescribing physician.

EVALUATION

History

The initial evaluation is the first step in the management of lymphedema, and a good evaluation begins with a detailed medical history. First, identify the causative factor, or the event that predisposed the individual to a compromised lymphatic function. This may include lymph node excision, radiation therapy, neoplasm, or paralysis. Note whether a precipitating event such as an injury, infection, air travel, or punctures to the skin may have triggered the onset of noticeable swelling. Also, rule out the possibility of heart failure, unidentified neoplasms, deep vein thrombosis, or other vascular disorders that may present similarly. Next, identify any other treatments for lymphedema that the patient may have had and whether they were successful. Also determine the patient’s lifestyle. Is he or she working, retired, or disabled? How has the swelling affected his or her daily life and function? Has the patient had to give up hobbies or has participation become more difficult? Finally, determine the patient’s goals for treatment. Perhaps his or her goals are to improve mobility, to restore a healthy body image, or simply to be able to lift a gallon of milk out of the refrigerator.

Physical Exam

After taking the medical history, it is time to move on to the physical exam. Observe the patient’s posture and alignment, and note any abnormalities. Observe the skin in the entire affected quadrant. Look for excessive skin folds, lack of bony prominences, scarring or adhesions, and skin changes such as thickening of the skin (hyperkeratosis), rough areas (papillomatosis), orange peel consistency (peau d’orange), or wounds (Figure 12-7). It may be necessary to perform a full musculoskeletal examination of adjacent joints including palpation, strength, range of motion, and special tests to address any concomitant problems that may have arisen as a consequence of the lymphedema.

The next step in the physical exam is to quantify the amount of edema in the extremity. This can be done using water displacement methods or calculated volume derived from girth measurements. It has been shown that geometric formulas correlate strongly with water displacement methods (Karges et al., 2003; Sander et al., 2002), and because girth measurement is quicker and easier to perform, it is the preferred method for many clinicians. It is also a good idea to take pictures initially and periodically during the course of treatment to help support the data.

where V is the volume, h is the height between intervals, C is the circumference at one end of the segment, and c is the circumference at the other end of the segment. The total volume is the sum of all segments. In unilateral involvement, the normal limb can be used to determine the amount of edema present. Progress should be tracked on a weekly basis to determine the efficacy of treatment (Casley-Smith, 1998; Karges et al., 2003; Sander et al., 2002).

LYMPH FLUID MOBILIZATION

There are several basic principles to keep in mind when performing lymph fluid mobilization:

STROKES

Standing circles.

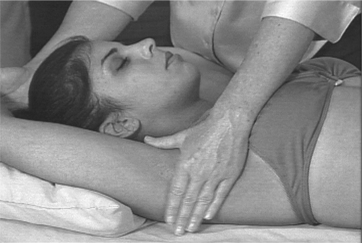

Applied mainly over lymph nodes and large areas such as the abdomen. Using the palmar surface of the hand or fingers, a stretch is applied to the skin in a circular pattern. Gentle pressure is applied in the direction of lymph flow. The pressure is then released while maintaining skin contact through the remainder of the arc (Figure 12-8).

Pump stroke.

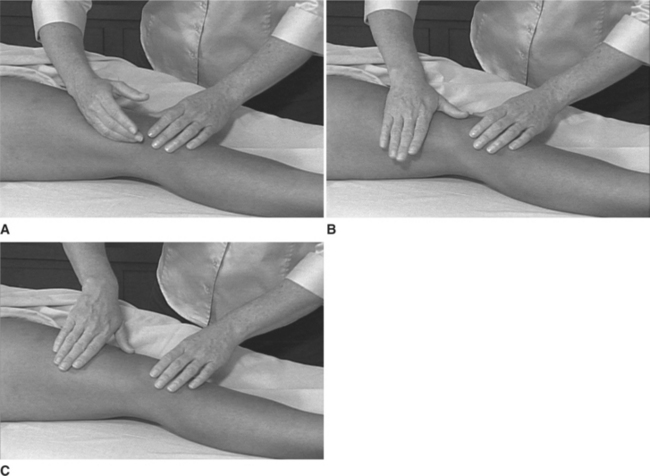

Applied mainly to the extremities. Place the hand on the extremity with the thumb and fingers facing proximally along the long axis. Begin with the hand cupped and thumb and distal fingers in contact with the skin. Slowly lower the hand and flatten the palm. Gradually return to the cupped position as you progress proximally along the extremity (Figure 12-9).

Turn stroke.

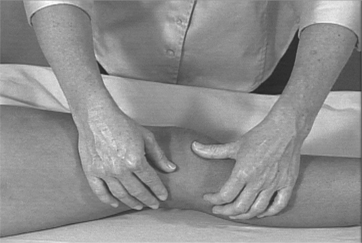

Applied mainly on large surfaces, such as the abdomen, chest, back, or thigh. Begin this stroke with the hand slightly cupped and the ulnar aspect of the hand in contact with the skin and facing the direction of intended lymph movement. Gradually transfer skin contact across the palm as the hand is brought into ulnar deviation and the palm flattens. Then lift the ulnar side of the palm slightly, and finish the stroke with the tips of the thumb, index, and middle fingers adducted slightly and in contact with the patient’s skin (Figure 12-10).

Thumb circles.

Used in very small or fibrotic areas. Apply a half-arc with the distal end of the left thumb. Apply a half-arc with the other thumb in the opposite direction. Alternate this movement as you progress in the desired direction of lymph flow (Figure 12-11).

These strokes may be combined in a variety of ways as you progress through the massage sequence.

SEQUENCES AND PATHWAYS

Common Sequences

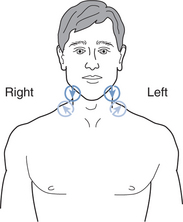

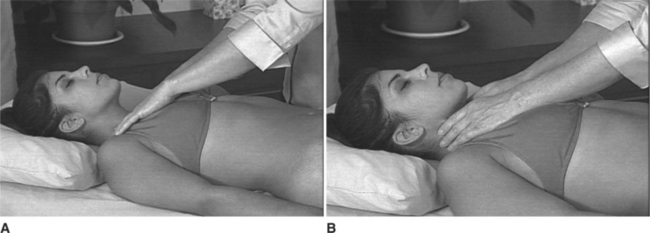

Brief Cervical Sequence (Figure 12-12)

Patient Is Supine (Figure 12-13)

Brief Abdominal Sequence (Figure 12-14)

Patient Is Supine (Figure 12-15)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree