Croup

Ellen R. Wald

The term croup describes a clinical syndrome characterized by a barking cough, hoarseness, and inspiratory stridor. This discussion of infectious nondiphtheritic croup is divided into four sections: (a) acute infectious laryngitis, (b) laryngotracheitis, (c) laryngotracheobronchitis (bacterial tracheitis), and (d) spasmodic croup.

ACUTE INFECTIOUS LARYNGITIS

Acute infectious laryngitis is experienced primarily by older children, adolescents, and adults during the respiratory virus season. The principal symptom of infection is hoarseness, which may be accompanied by variable upper respiratory symptoms (coryza, sore throat, nasal stuffiness) and constitutional symptoms (fever, headache, myalgias, malaise). The presence of associated complaints varies with the infecting virus: adenoviruses and influenza viruses may cause more systemic disease; parainfluenza viruses, rhinoviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus most often cause mild illness.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of acute laryngitis is made on clinical grounds, and laboratory evaluation is unnecessary. In febrile, school-aged children who experience hoarseness, complain of sore throat, and have tender anterior cervical adenopathy, a throat culture to detect Streptococcus pyogenes may be appropriate. Hoarseness without any other respiratory symptoms may represent voice abuse.

Therapy

Acute infectious laryngitis virtually always is self-limited. Treatment consists of symptomatic therapy with fluids and humidified inspired air. Voice rest is beneficial. Protracted episodes of hoarseness (no improvement after 7 to 10 days) suggest an underlying anatomic abnormality.

ACUTE LARYNGOTRACHEITIS

Usually, croup refers to acute laryngotracheitis, a respiratory disease prevalent in preschool children. Acute laryngotracheitis is seen in children of any age but is most common between the first and third years of life; boys are affected more often than are girls. The causative agents are respiratory viruses exclusively, and frequently the illness occurs in epidemic patterns. Most frequently, the viruses implicated are parainfluenza types 1 and 3, but influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza 2, adenoviruses, and herpes simplex virus have been cited as other causes. Mycoplasma pneumoniae also may cause croup. In areas in which measles is endemic, severe croup may dominate the clinical picture. In summertime croup, the enteroviruses (coxsackievirus A and B and echovirus) or parainfluenza type 3 are the usual cause.

Pathophysiology

The causative virus is transmitted by the respiratory route, either via direct droplet spread or hand-to-mucosa inoculation. After acquisition, primary viral infection involves the nasopharynx. Viral replication ensues, producing nasal symptoms, and infection spreads locally and involves the larynx and trachea. Endoscopically, the mucosa is erythematous and swollen. Histologic evaluation reveals mucosal edema with cellular infiltration of the lamina propria, submucosa, and adventitia. The cellular constituents include lymphocytes, histiocytes, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

The usual onset of croup is with the signs and symptoms of a common cold: coryza, nasal congestion, sore throat, and cough, with variable fever. The cough becomes prominent, with a barking quality (akin to that of a puppy or seal), and the voice becomes hoarse. Many children with this syndrome never visit a physician. Such children may begin to have evidence of respiratory distress, however, with the onset of tachypnea, stridor (when agitated or crying), nasal flaring, and suprasternal and intercostal retractions. The increase in respiratory distress prompts a visit to the physician or emergency department. Usually, the illness peaks in severity over 3 to 5 days and then begins to resolve. Most characteristically, the signs and symptoms worsen in the evening.

Diagnosis

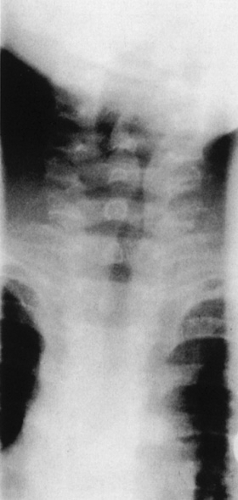

In typical cases of acute laryngotracheitis, the diagnosis is made easily on clinical grounds, and no radiography or blood tests are required. If anteroposterior radiography is performed, a so-called steeple sign may be seen as a consequence of subglottic swelling (Fig. 255.1). Usually, the blood count is fewer than 10,000 cells per cubic millimeter, with a predominance of lymphocytes. Indications for hospitalization, undertaken in approximately 10% of children with laryngotracheitis, include the presence of stridor, anxiety or restlessness, cyanosis, retractions at rest, or hypoxemia. In addition, children with a history of croup or previous airway intubation may benefit from hospitalization. Children for whom close follow-up cannot be arranged or whose families cannot provide the necessary observation and care also should be admitted to the hospital.

Therapy

As laryngeal inflammation increases and secretions accumulate, respiratory distress increases, and complete obstruction may occur. Almost always, this progression is gradual and is

signaled by slowly increasing respiratory rate and effort, increased stridor at rest, and pallor or cyanosis. Agitation increases and air entry is poor. In approximately 5% of hospitalized patients, intubation is required to overcome the respiratory obstruction. Children who have a deteriorating respiratory status should be monitored in an intensive care unit by staff skilled in the care of pediatric patients.

signaled by slowly increasing respiratory rate and effort, increased stridor at rest, and pallor or cyanosis. Agitation increases and air entry is poor. In approximately 5% of hospitalized patients, intubation is required to overcome the respiratory obstruction. Children who have a deteriorating respiratory status should be monitored in an intensive care unit by staff skilled in the care of pediatric patients.

One of the most important principles of treatment in patients with croup or other upper airway problems is minimal disturbance. Any stimulus that upsets affected children will result in crying, which causes hyperventilation and an increase in respiratory distress. The parents should be encouraged to hold and comfort such children whenever possible, and invasive procedures should be kept to a minimum.

Treatment strategies for acute infectious laryngotracheitis have included mist, racemic epinephrine, and corticosteroids. Although not subjected to study until recently, mist therapy has been considered standard management. Several investigations have suggested that mist is of no demonstrable benefit; however, this remedy still is used frequently. Racemic epinephrine, in use since 1971, is a potentially life-saving therapy in croup patients who are in moderate to severe respiratory distress. Racemic epinephrine is an equal mixture of the D- and L-isomers of epinephrine. The dose is 0.5 mL of a 2.25% solution diluted with 3.5 mL of water (1:8), delivered via a nebulizer with a mouthpiece held in front of the child’s face. Administration results in rapid clinical improvement; by its beta-adrenergic vasoconstrictive effects on mucosal edema, racemic epinephrine increases the airway diameter. The peak effect is observed in 2 hours. Accumulating evidence substantiates that patients who receive a single dose of epinephrine do not necessarily require hospitalization (as was the practice in the 1980s). Affected children may be discharged to home if, in addition to receiving epinephrine, they were treated simultaneously with dexamethasone and remain improved during a 3-hour observation period. The dosing interval for epinephrine in hospitalized patients depends on the severity of the laryngotracheitis; it can be administered every 20 to 30 minutes in the intensive care unit, where monitoring is possible, but usually is spaced 3 to 4 hours apart when such patients are in a regular hospital unit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree