Chapter 22 Craniosacral Therapy

Initial Examination

Initial Examination

Client Goals: Decrease her thoracic pain and discomfort

Employment: Assists at daughter’s school

Recreational Activities: Walking

General Health: Generally good with the exception of diabetes

Reevaluation

Reevaluation

During the reevaluation the client revealed that she had a history of Ménière’s disease and frequently suffered from nausea, vertigo, and tinnitus. She asked if spinal manipulations ever helped Ménière’s disease or if the chiropractor knew of any techniques that may help reduce her symptoms. Given this new information and request, the chiropractor reexamined the client.

The scenario presented in this chapter includes a client with thoracic pain and Ménière’s disease whose care is managed by a chiropractor. Although chiropractics is considered by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) to be a complementary practice (see Chapter 18) the same clinical decision-making process described in Chapter 2 can be used by any licensed health care provider who considers providing an intervention not traditionally taught in their professional curriculum. Regardless of the discipline, all heath care providers are encouraged to be knowledgeable about one’s own professional scope of practice before the integration of a complementary therapy. This knowledge, along with information about other legal, ethical, and cultural issues (see Chapter 3), will be helpful for managing patients and professional liability.

INVESTIGATING THE LITERATURE

Preliminary Reading

In this case, the client presents with Ménière’s disease, a condition that may be unfamiliar to health care providers who do not specialize in vestibular rehabilitation. An overview of the symptoms and impairments associated with Ménière’s disease can be found in resources listed in the references at the end of this chapter. They include books1–4 and reputable medical websites.5–7

Ménière’s Disease

Ménière’s disease is an idiopathic inner ear disorder. Also known as endolymphatic hydrops, this condition is characterized by episodic attacks of fluctuating hearing loss, a sensation of “fullness” in the ear, tinnitus, rotatory vertigo, postural imbalance, nystagmus, nausea, and vomiting. Although severe vertigo can persist from 30 minutes to 24 hours, less severe symptoms can last 72 hours. Residual instability and hearing loss may continue for several more days or weeks and then return to their pre-attack status. As the disease progresses, hearing may fail to return, whereas the symptoms of vertigo may diminish in severity and frequency.2

Several factors have been attributed to Ménière’s disease, but a clear etiology of the condition remains elusive. The presence of endolymphatic hydrops in persons with Ménière’s disease is considered to be a function of malabsorption of endolymph in the endolymphatic duct and sac. This condition can create obstructions and increased hydraulic pressure within the inner ear’s endolymphatic system, which potentially affects the anatomical relationships between the temporal bone, the organ of Corti, the utricle, and the saccule.6 Of note are observations that lesions of the temporal bone associated with hydrops include temporal bone fractures, atrophy of the sac, and narrowing of the lumen in the endolymphatic duct, which prompts some health professionals to “postulate a cause-and-effect relationship between constricted anatomy in the temporal bone and malabsorption of the endolymph.”2

Diagnosis

A panel of blood tests, for example, may be helpful to rule out infection and metabolic and hormonal imbalances, which can present symptoms similar to those of Ménière’s disease. Imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans, can be used to identify the presence of anatomical abnormalities and lesions that may cause Ménière’s disease–like symptoms. Other tests, such as audiometry, can be helpful for documenting fluctuations in hearing acuity, a common finding in Ménière’s disease, whereas transtympanic electrocochleography (ECoG) can be used to detect distortion of the inner ear and the likely presence of hydrops, an observation consistent with Ménière’s disease.5,6

In keeping with the recommendation to follow the longitudinal course of the disease and exclude conditions that may mimic the symptoms of Ménière’s disease, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery’s Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium developed a diagnostic guideline for Ménière’s disease that can be found in Box 22-1.7

Box 22-1 Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Ménière’s Disease

Rights were not granted to include this box in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

From Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Meniere’s disease.

Treatment

Because the etiology of Ménière’s disease is unclear, medical treatment for it is focused primarily on relief of the client’s symptoms. Vertigo sometimes can be managed with medications considered to be vestibulosuppressants, such as meclizine (Antivert), diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and alprazolam (Xanax), whereas prochlorperazine (Compazine) or dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) may be prescribed for nausea. A short course of steroids appears to be helpful to treat acute attacks of Ménière’s disease, whereas diuretics have been used prophylactically to reduce endolymphatic pressure. Clients also are advised to make dietary changes that may help manage their condition. Avoidance of salt is one of the primary recommendations because sodium appears to play a role in increased fluid retention of the inner ear. In addition, clients often are asked to limit food and substances that appear to be “triggers” for acute attacks. These trigger substances include caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and foods with high cholesterol and carbohydrate content.5,6

Surgical treatment for Ménière’s disease is reserved for clients for whom conservative medical treatment has failed and attacks are frequent and severe. Even with these conditions, surgical intervention is controversial. During one procedure, the petrous bone is removed so that the endolymphatic reservoir sac can expand and dissipate pressure. A shunt also can be provided so that fluid can drain from the endolymphatic space to the mastoid or subarachnoid space. Success rates are reported to be 60% to 80%, although critics argue that this surgery is no more effective than sham surgery, which suggests that the benefits are due to the placebo effect. A vestibular nerve section is the most common surgery for persons with unilateral Ménière’s disease and severe vertigo. Vertigo control with hearing preservation occurs in 95% of the surgeries. Postoperative vestibular rehabilitation frequently is required to ensure accommodation to unilateral vestibular functioning. A labyrinthectomy, which is less invasive than a vestibular section, is indicated only for clients whose hearing has been destroyed by the disease. The success rate for labyrinthectomy is better than 95%, with recovery enhanced by postsurgical vestibular rehabilitation. The newest treatment approach for severe Ménière’s disease is transtympanic perfusion of gentamicin, in which the medication is applied through a myringotomy into the middle ear cavity, where it is then absorbed through the membrane of the inner ear. Early success rates appear to be favorable, although long-term studies have yet to be completed.8

Cranial Osteopathy

Dr. Andrew Taylor Still (1828-1917), considered to be the founder of osteopathy (refer to Chapter 18) believed that the body is a self-regulating, self-healing, integrated unit. He theorized that most diseases and pathological conditions were either directly or indirectly caused by vertebral misalignment. Therefore manipulation of the spine, with the intent to correct vertebral displacement, would help to ameliorate abnormal conditions elsewhere in the body.9 This theory and Still’s approach to medicine were controversial during the late nineteenth century. Nevertheless, Still’s successes in treatment of clients using manual therapy or what was then being called “osteopathy” brought him notoriety, and in 1892 he established the American School of Osteopathy in Kirksville, Missouri.

A student of Still’s, William G. Sutherland, DO, was fascinated with the design of the human skull and believed that the cranial sutures were actually joints that did not calcify or fuse completely during maturation. Sutherland proposed that interosseous cranial motion was rhythmic and constant throughout life and, in fact, was crucial to maintaining health. When the interosseous cranial motion was abnormal or restricted, then abnormal symptoms or conditions would emerge.10 Sutherland experimented with his own head by palpating and restricting cranial movement. He then began gently palpating the heads of others and claimed that he could sense subtle rhythmic movement of the cranium. Sutherland also proposed, based on his palpations and observations, that the sacrum had palpable movement that was in synchrony with cranial motion.10 Sutherland argued that these structures were linked by the spinal dura mater, which allowed the motion at the occiput to influence the motion at the sacrum, and vice versa. Disruption of the synchronicity could be represented by physiological or anatomical abnormalities.

Craniosacral Therapy

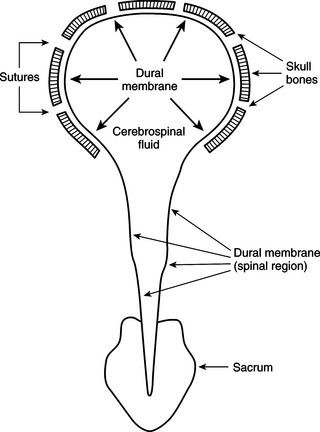

Sutherland’s concepts and theories were known in the osteopathic community of health care providers but were not even considered in the practice of traditional medicine. In the 1970s, osteopathic physician John E. Upledger worked with a team of physicians and scientists at Michigan State University to investigate Sutherland’s concepts of cranial bone movement and a craniosacral system. From their work, Upledger developed CST, a manual method to evaluate and treat the craniosacral system consisting of the cranium, brain, dura mater, arachnoid membrane, pia mater, spinal cord, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and sacrum.10

Upledger and Vredevoogd10 have suggested that, based on its anatomical structure, the craniosacral system is a distinct physiological system and is intimately associated with the central and autonomic nervous systems and the neuromuscular and endocrine systems. They describe the craniosacral system as a semi-closed hydraulic system formed by the dura mater, in which the choroid system within the brain ventricles acts as the CSF intake component and the arachnoid system serves as the outflow component (Figure 22-1). This continuous, rhythmic flow of fluid creates subtle movement of the dura mater membranes, which, because they are attached to the skull, vertebral column, and sacrum, can affect the functioning of multiple systems.11 Restrictions in normal physiological motion of the craniosacral system have been associated with a wide range of conditions including, but not limited to, neck and back pain, headache, autism, scoliosis, fibromyalgia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and temporomandibular joint syndrome.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Evaluation

Evaluation Plan of Care

Plan of Care Reexamination

Reexamination