Corrective Osteotomy for Metacarpal and Phalangeal Malunion

Nilesh M. Chaudhari

Mohamed Khalid

Thomas R. Hunt III

DEFINITION

Malunion results when a fracture fragment heals in incorrect anatomic alignment.

ANATOMY

Metacarpals and phalanges are tubular structures with a smooth dorsal surface covered by the extensor tendon and its expansions.

Metacarpals are triangular in cross-section. The medial and lateral surfaces meet at the volar ridge, providing attachment to the interossei. These attachments together with the intermetacarpal ligaments proximally and distally help splint fractured bones, making functionally significant malunions of the ring and small metacarpals less common.

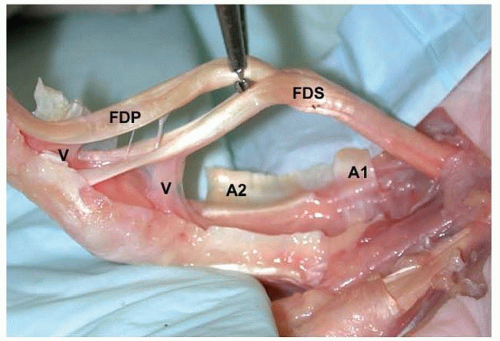

Phalanges are bean-shaped in cross-section. The volar aspects of the proximal and middle phalanges are in intimate relation to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) tendons, particularly in the region of the annular pulleys (FIG 1).

As a result, the tendons are vulnerable to damage from drills and screws used in a dorsovolar direction. This problem is especially significant in the region of the annular pulleys, where the tendons are strapped against the volar cortex, rendering them vulnerable to damage.

PATHOGENESIS

Malunions most often occur secondary to lack of treatment or inadequate nonoperative care.9

Malunion following internal fixation is uncommon, but when present usually results from inadequate stability or poor patient compliance.

Extra-articular malunions (EAM) often are multiplanar, but usually there is one major component to the deformity that causes the functional deficit.8

The more proximal the malunion, the greater the deformity.

Just 1 degree of rotation at the fracture site may translate to 5 degrees at the fingertip.6

Five degrees of fracture malrotation can cause 1.5 cm of digital overlap when the fingers are flexed.2

Soft tissue pathology such as neurovascular deficits, trophic changes, joint contractures, and tendon adhesions can coexist.

Results of corrective osteotomy are significantly poorer in the presence of such complicating factors.1

NATURAL HISTORY

Significant EAM can cause crossing or scissoring of fingers, pain due to distortion of joints, disturbance of muscle/tendon balance, and reduction of grip strength.1

EAMs associated with shortening can lead to an extension lag proportional to the degree of shortening. The effect is more pronounced in proximal phalanges compared to metacarpals.13

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The value of a good history and physical examination cannot be overemphasized. The decision as to whether surgical treatment is to be offered depends almost entirely on a history suggestive of a significant functional impairment or pain.

Injury specifics

The original injury and method(s) of treatment

Location

Phalanx versus metacarpal

Extra-articular versus intra-articular versus combined deformities

History of complicating factors, for example, infection and chronic mediated pain syndrome

Duration of malunion, particularly relevant in deciding surgical strategy (reducing the fracture vs. osteotomy)

Associated injuries such as soft tissue defects and neurovascular injuries

Specific patient characteristics

Skeletal maturity

Hand dominance

Degree of deformity, swelling, stiffness, weakness of grip, and pain

Occupation and avocational pursuits as well as patient expectations and goals

Ability to cooperate with postoperative therapy regimen

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Good-quality radiographs taken in three precise planes (anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique) are sufficient for simple EAMs.

Radiographs of the opposite hand are helpful in preoperative planning for complex EAMs.

IAMs and combined malunions may require computed tomography (CT) scans with three-dimensional reconstruction.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Fibrous nonunion

Nonunion with soft tissue contracture

Sequelae of epiphyseal injury or growth arrest

Erosive arthritis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Hand therapy is directed toward maximizing the range of motion (ROM) of the digits, promoting optimal tendon excursion, and improving the grip strength.

In less dramatic deformities, physical therapy is the first-line treatment. Many patients will gain enough functional improvement that they decide to “live with” the deformity.

Initiation of therapy allows the opportunity to assess the patient’s personality with respect to compliance and realistic expectations.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Timing of Correction

Treatment of nascent malunions results in improved outcomes.

IAMs must be corrected as soon as possible if there is a significant articular step and no overwhelming technical difficulties are anticipated.1

In the case of an EAM, after 6 to 8 weeks from the injury, a “wait and watch” policy before osteotomy is advisable to see whether the malunion causes significant functional or cosmetic problems.

Location of Correction

At or near the apex of the deformity for angular and complex EAMs

In the proximal metaphysis of the malunited bone for rotational EAMs. With improved osteotomy techniques and fixation implants, a proximal metacarpal osteotomy is no longer recommended for treatment of a P1 rotational malunion.1

Type of Osteotomy

For most angular EAMs, a closing wedge osteotomy is preferable, especially in the setting of intrinsic tightness. This approach is most commonly used for dorsal apex metacarpal malunions.

An opening wedge osteotomy is best for angular EAMs in the setting of an extension lag and pseudoclaw deformity, which are more commonly seen in apex volar phalangeal malunions.

An incomplete osteotomy may be used for either of these cases.

For rotational and combined rotational/angular EAM correction, a complete osteotomy is required.6 Metacarpal neck EAM from a previous boxer’s fracture without significant shortening may be corrected with a pivot osteotomy.12

Condylar advancement osteotomy11 is suitable for IAM correction in many cases.

Severity of Deformity

Malunion does not always mandate a corrective osteotomy. Patients possess a significant capacity to adapt to minor deformities. For instance, slight overlap of adjacent digits due to rotational malunion may be unsettling and unsightly, but it is consistent with good hand function.8 Similarly, a proximal diaphyseal malunion of the small finger metacarpal can contribute to tendon imbalance and flexion contracture of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, but the hand may function effectively.10

Multifragment IAMs and those with established posttraumatic arthrosis are best treated by arthrodesis or arthroplasty rather than repositioning osteotomy.

Preoperative Planning

In addition to precise evaluation of the bony deformity, careful assessment of the soft tissue envelope, gliding capacity of the flexor and extensor tendons, joint mobility, and neurovascular status is critical.

Plan for adjunct procedures (eg, tenolysis, capsulotomy) that may be required.

Determine the optimal location for placement of internal fixation.

Decide on opening or closing wedge osteotomy. In the presence of an extension lag, an opening wedge is preferred, whereas in the presence of intrinsic tightness, a closing wedge is preferred.

Provide for soft tissue coverage as needed.

Preoperative templates are created for bony correction.

The proximal and distal fragments are each outlined then superimposed over an outline of the contralateral uninjured bone.

The type and location of the osteotomy, the size of the bone graft needed (in the case of an opening wedge osteotomy), as well as the method of fixation are determined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree