Corrective Osteotomy for Distal Radius Malunion

David Ring

Diego Fernandez

Jesse B. Jupiter

DEFINITION

Distal radius malunion is best defined as malalignment associated with dysfunction.

Malalignment does not always result in dysfunction. In particular, the vast majority of older, low-demand patients function very well with deformity.

Pain can be the most difficult to associate with deformity. Osteotomy for pain—as with any surgery for pain—is relatively unpredictable and should be undertaken with caution. Carpal malalignment, ulnocarpal impaction, and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) malalignment are all potentially painful and can be variably addressed.

The relationship between distal radius malunion and carpal tunnel syndrome is debated. Some surgeons claim a direct causal relationship as well as the ability to improve carpal tunnel syndrome with osteotomy alone.

ANATOMY

Loss of alignment can be measured on radiographs.

Angulation of the articular surface on the lateral view is measured as the angle between a line connecting the dorsal and palmar lips of the distal radius articular surface on the lateral view and a line perpendicular to the radius shaft.

Ulnarward inclination (often called radial inclination, a misnomer because the articular surface tilts toward the ulna) is measured as the angle between a line connecting the ulnar limit and the radial limit of the distal radius articular surface on the posteroanterior (PA) view and a line perpendicular to the radial shaft.

Ulnar variance is a better measure of shortening of the radius than radial length. It is measured as the distance between two lines drawn perpendicular to the radial shaft on the PA view, one at the level of the most ulnar corner of the lunate facet and the other at the distal limit of the ulnar head.

Positive ulnar variance means that the ulna is longer than the radius. Negative means the ulna is shorter.

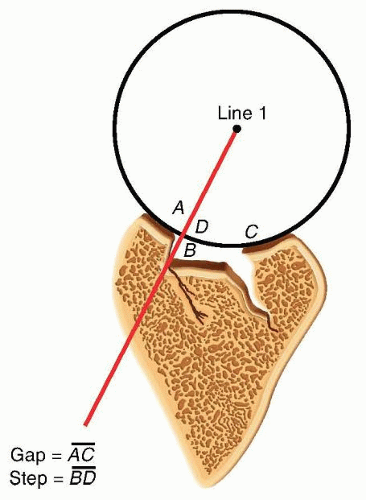

Loss of articular surface alignment can be measured on radiographs as gap, step, or subluxation.

This is most accurately measured using computed tomography (CT) images (FIG 1).

Sources of variability in radiographic measurements include variation in the radiographs, imprecision in the measurement techniques, and imprecision in the selection of the points of reference.

PATHOGENESIS

Fractures of the distal radius heal rapidly. A malaligned healing fracture can be considered a malunion within 4 to 6 weeks of injury.

Risk factors for fracture instability, loss of reduction, and malunion include age older than 60 years, more than 20 degrees of dorsal angulation, dorsal metaphyseal comminution, comminution extending to the volar metaphyseal cortex, associated fracture of the ulna, and displaced articular fracture.

Risk factors for fracture instability include age, metaphyseal comminution, dorsal tilt, ulnar variance, and lack of functional independence.

Manipulation of previously reduced fractures that redisplace in a cast or splint signifies instability and is not worthwhile.

Limitations of various treatment techniques may contribute to creation of a malunion.

Percutaneous pins alone may not be sufficient to maintain alignment when there is substantial metaphyseal comminution.

External fixation alone without ancillary percutaneous pin fixation of the fracture

Early removal of pins or an external fixator. Settling of the fracture can also be observed after implant removal more than 6 weeks after injury, particularly when there is substantial metaphyseal comminution.

Nonlocked plates may loosen in osteopenic metaphyseal bone.

Complacence must be avoided. Many older patients desire optimal wrist alignment and function, and treatment decisions should not be made on chronologic age alone.

NATURAL HISTORY

Ulnar-sided wrist pain can improve for a year or more after fracture of the distal radius, so patience is warranted.

Lack of forearm rotation may be related to capsular contracture or bony malalignment. For slight malunions, patience with exercises and rehabilitation is advisable.

Although it is often stated that an extra-articular distal radius malunion leads to future arthrosis, there are no data to support this contention.

After a recovery period of 1 to 2 years from fracture, the functional deficits seem fairly stable.

Articular incongruity or subluxation in relatively nonarticular areas can be reasonably well tolerated, but in most cases, intra-articular incongruity will lead to arthrosis, pain, and dysfunction. There is no clear time frame for these changes— indeed, symptoms do not correlate well with radiographic anatomy or arthrosis and the predictors of arthrosis are not well established.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Pain should be very discrete and specific. It is important that there be a direct correlation of the pain with a clear operative target. Vague, diffuse, or disproportionate pain should not be treated with osteotomy. Pain alone is not a good indication for osteotomy, so the interview should elicit specific aspects of the pain for which there is a good operative target and the risks of surgery are justified.

Lack of motion should be clearly due to malalignment and not due to pain or protectiveness—likewise for instability of the DRUJ.

Range of motion: A goniometer is used to measure wrist flexion, extension, radial and ulnar deviation, supination, and pronation.

Ulnocarpal compression: The carpus is forcefully ulnarly deviated toward the ulna.

Consistent reproduction of usual pain with ulnar deviation tasks is consistent with ulnocarpal impaction.

The examiner can test for DRUJ instability by stabilizing the radius and trying to subluxate the distal ulna dorsal and volar from the sigmoid notch of the radius.

Substantially, less stability than the opposite side may correlate with symptomatic DRUJ instability, but this is a very difficult and subjective test.

Scaphoid shift test: Instability compared to the opposite wrist would indicate a possible scapholunate interosseous ligament tear, indicating a potential dissociative rather than the typical nondissociative carpal malalignment usually associated with distal radius malunion.

Grip strength is one of the measure of wrist dysfunction, but it is largely determined by pain and effort—both strongly influenced by psychosocial factors.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

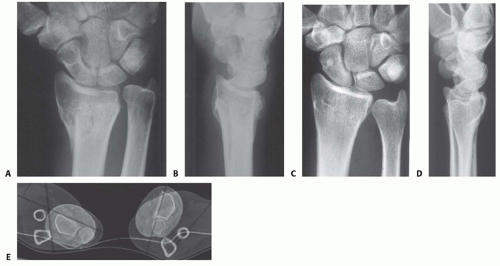

PA and lateral radiographs of the wrist (FIG 2A-D) can be supplemented by specific radiographs for evaluation of the joint surface, particularly for potential articular malunions.

Comparison with the opposite, uninjured wrist is useful and serves as a template for surgical correction.

CT, particularly three-dimensional CT, is useful to precisely evaluate the joint surfaces (FIG 2E).

Neurophysiologic tests (nerve conduction velocity and electromyography) are ordered to evaluate any symptoms or signs of carpal tunnel syndrome that may need to be addressed.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Stiffness: capsular stiffness and tendon adhesions

Numbness: idiopathic carpal tunnel syndrome

Pain: another discrete source of pain or even nonspecific pain

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management is appropriate for low-demand and infirm individuals. Splints are weaned after 6 weeks of cast immobilization. Patients who struggle to regain motion may benefit from working with an occupational therapist or a certified hand therapist. Normal activities are resumed in 3 or 4 months. The patient may return every 2 or 4 months or so until satisfied with the result.

Patience is warranted in many situations, particularly for patients with ulnar-sided wrist pain thought to be due to an extra-articular malunion.

This discomfort is the last pain to go away after a distal radius fracture and can last up to a year.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is appropriate when a radiographic deformity correlates with a specific anatomically correctable problem and the deformity is associated with a substantial risk of dysfunction or arthrosis.

The patient must understand the risks and benefits of intervening.

The surgeon should be wary of pain as the primary complaint because pain is strongly influenced by psychosocial factors, and pain relief is an achievable goal only when consistent with an objective, correctable anatomic deformity such as discomfort clearly associated with a substantial ulnocarpal impingement.

When the issue is restriction of motion and there is less than 20 degrees of dorsal tilt or less than 5 mm of ulnar positive variance, a nonoperative approach may be warranted.

There are no fixed rules or thresholds for acceptable alignment. The correlation with symptoms and disability is more important.

Intra-articular osteotomies should be considered only when the malalignment is simple and the planned correction is straightforward.

For instance, osteotomy of a volar shearing fracture would be considered when the fragment is large, there is little or no articular comminution or impaction, and the dorsal fragments are not healed in a malaligned position.

Distal radius osteotomy need not be performed urgently. The patient should have demonstrated excellent exercise skills and full finger motion and there should be no significant nerve or tendon dysfunction or edema.

In the case of an intra-articular malunion, intervening early (optimally within 10 weeks) when the fracture is not completely healed may take precedence over these concerns.

Preoperative Planning

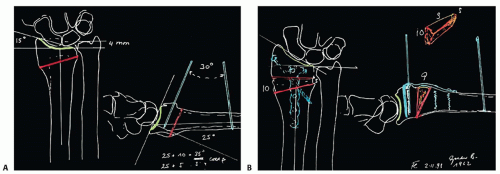

The desired angular, rotational, and length corrections are planned based on preoperative radiologic studies, including a radiograph of the opposite wrist if uninjured (FIG 3A,B).

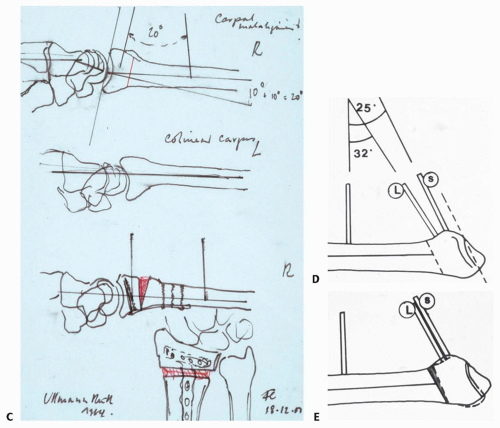

It can be useful to draw and write out a reconstruction plan, particularly for complex malunions (FIG 3C-E). In that way, every contingency is anticipated and the surgery is likely to go more smoothly.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine with the arm supported on a hand table.

A nonsterile pneumatic tourniquet is used and inflated after exsanguination and before the skin incision.

Approach

The operative approach is either dorsal or volar, depending on the deformity and the chosen surgical technique.

FIG 3 • A,B. Preoperative plans for dorsal osteotomy in the patient in TECH FIGS 1, 2 and 3: preosteotomy plan (A) and postosteotomy and corticocancellous bone grafting plan (B). (continued) |

FIG 3 • (continued) C. Preoperative plan for an extra-articular osteotomy through a volar approach in the patient in TECH FIGS 4 and 5. D,E. Preoperative plans for an intra-articular dorsally angulated malunion in the patient in TECH FIG 6. (Copyright Diego Fernandez, MD, PhD.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|