Conversion of Painful Ankle Arthrodesis to Total Ankle Replacement

Mark E. Easley

Manuel J. Pellegrini

INTRODUCTION

Conversion of the painful ankle arthrodesis to total ankle replacement (TAR) remains controversial. Despite satisfactory outcomes of this technique which have been published in the recent orthopedic literature,1,2 not all foot and ankle surgeons performing TAR have embraced this surgical practice. Moreover, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests “prior arthrodesis at the ankle joint” as a contraindication to at least one currently available TAR.3 Nonetheless, an increasing number of foot and ankle specialists are converting painful ankle arthrodeses to TAR.

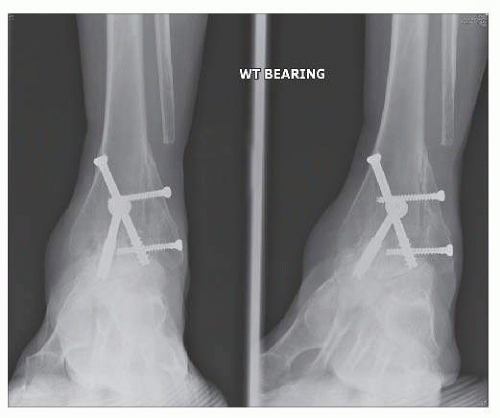

Results for ankle arthrodesis are generally favorable, and the literature suggests that well-performed ankle arthrodesis at intermediate follow-up has functional outcomes comparable to TAR.4,5,6,7 and 8 In short to intermediate follow-up, the term “painful ankle arthrodesis” typically refers to a painful ankle nonunion or malunion.1,2,9,10 and 11 Revision ankle arthrodesis or realignment osteotomy with or without extension of the arthrodesis to the hindfoot is considered a salvage procedure with satisfactory but not always favorable outcomes.1,2,9,10 and 11 In select patients, an ankle nonunion may be successfully converted to a TAR.1,2 At longer follow-up of successful ankle arthrodeses, the term painful ankle arthrodesis may be a misnomer as symptoms progress with the development of symptomatic adjacent hindfoot arthritis6,12,13 (Fig. 16.1).

In our opinion, for many foot and ankle specialists a paradigm shift has evolved: whereas before TAR may have been considered as an alternative to ankle arthrodesis, more recently, with promising results of TAR, ankle arthrodesis has undergone a role reversal to become an alternative to TAR. In fact, conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR has gained a foothold in orthopedic practice because of the challenges surgeons experience with management of the painful ankle arthrodesis. We recently reported a high nonunion rate for subtalar arthrodesis performed in patients with a prior ipsilateral ankle arthrodesis,14 supporting a prior publication of similar but limited experience.15 Although recent literature suggests satisfactory outcomes with concomitant ankle and hindfoot arthrodesis,4,16 these results are often for patients in need of salvage for a complex ankle hindfoot deformity.4,9,11,16,17 Armed with realistic expectations through appropriate patient education, patients with tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) arthrodeses may have lower outcome expectations than patients undergoing reconstructive procedures isolated to the ankle,4 including TAR, and many surgeons’ experience is that functional outcomes after TTC arthrodesis are often not favorable.1,2 Ankle fusion takedown and

conversion to TAR, with or without simultaneous hindfoot arthrodesis, have been proposed for patients with ankle arthrodesis and symptomatic adjacent hindfoot arthritis in an effort to perhaps improve functional outcomes versus those with extension of the arthrodesis to the hindfoot.1,2 In this chapter, we share our institution’s experience with conversion of the painful ankle arthrodesis to TAR.

conversion to TAR, with or without simultaneous hindfoot arthrodesis, have been proposed for patients with ankle arthrodesis and symptomatic adjacent hindfoot arthritis in an effort to perhaps improve functional outcomes versus those with extension of the arthrodesis to the hindfoot.1,2 In this chapter, we share our institution’s experience with conversion of the painful ankle arthrodesis to TAR.

INDICATIONS

In our experience and the experience of other foot and ankle specialists who perform conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR, indications for this procedure include (1) painful ankle nonunion (Fig. 16.2) and (2) ankle arthrodesis with symptomatic adjacent hindfoot arthritis1,2 (Fig. 16.1). Conversion of the symptomatic ankle arthrodesis to TAR represents an alternative to amputation.1

CONTRAINDICATIONS

In our opinion, contraindications to conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR include all contraindications to TAR such as (1) active infection, (2) avascular necrosis, (3) severe deformity that would not allow a congruent alignment of the TAR with conversion from ankle arthrodesis, (4) neuromuscular disease with lack of adequate muscle function about the ankle, particularly dorsiflexion, (5) peripheral vascular disease, (6) poor skin and soft tissue quality about the ankle, (7) peripheral neuropathy or neuroarthropathy, and (8) bone stock that is inadequate to support the implant.

Inadequate bone stock to support the implant includes a particular subset of patients unique to prior ankle arthrodesis who should not be considered for conversion to TAR: patients who have undergone ankle arthrodesis via a transfibular approach in which the distal fibula was sacrificed, particularly with residual valgus deformity (Fig. 16.3). Much like prior authors reporting this procedure,1,2 we consider this group of patients a contraindication for conversion to TAR since lateral support for the implant will be forfeited; however, in select cases, the fibula may be reconstructed adequately to permit successful conversion to total ankle arthroplasty (TAA).2,18 The potential for future conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR has been a major influence on the recent trend for ankle arthrodesis performed via an anterior approach with preservation of the ankle anatomy, including the malleoli.7 In fact, many foot and ankle specialists embracing TAR recommend against transfibular ankle arthrodesis, particularly if the distal fibula is to be sacrificed. In our experience, transfibular ankle arthrodesis with preservation of the fibular, that is, using the fibula as an on-lay strut graft, is not a contraindication for conversion to TAR since lateral bony support is preserved1 (Fig. 16.4). However, in our opinion, anterior approach ankle arthrodesis with preservation of the malleoli lends itself better for conversion to TAR and should be favored, especially in young people for whom ankle replacement may be many years in the future.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION, PLANNING, AND CONCEPTS

Once the proper indications have been met, preoperative preparation and planning for conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR is not much different from that for primary TAR, and primary TAR implants may be used in a majority of conversions

to TAR.1,2 Since conversion to TAR represents a repeat surgery, the surgical approach must be carefully planned, particularly if prior anterior skin incision(s) hase been made. For the majority of currently available TAR implants, a standard anterior longitudinal approach is necessary. One major difference in conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR from primary TAR is that hardware crosses the ankle joint at the arthrodesis site and when removed, often leaves large bone defects on both the tibial and talar sides, creating concern for adequate bony support for the implants (Fig. 16.5). This concern has further prompted many foot and ankle surgeons to perform ankle arthrodesis with plating via an anterior approach, when consideration is given to potential (eventual) conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR7 (Fig. 16.6). Converting an ankle arthrodesis performed with plating via an anterior approach to TAR is relatively straightforward, using the same anterior approach, with direct access to the hardware. Moreover, plating in lieu of screws crossing the arthrodesis site results in minimal compromise to the bone surfaces used to support the TAR implant(s). When multiple large diameter crossing screws were used for ankle arthrodesis, consideration may be given to staging the conversion to TAR several weeks to months after hardware removal with bone grafting in an attempt to allow some bone formation in the bony defects prior to conversion to TAR. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan prior to TAA may be useful to (1) identify distal tibial or talar bone defects that may weaken the support for the implanted components, (2) confirm radiographic suspicion or tibiotalar nonunion, and (3) evaluate the extent of hindfoot arthritis. When hardware is present, we recommend CT scanning with a metal-suppression protocol.

to TAR.1,2 Since conversion to TAR represents a repeat surgery, the surgical approach must be carefully planned, particularly if prior anterior skin incision(s) hase been made. For the majority of currently available TAR implants, a standard anterior longitudinal approach is necessary. One major difference in conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR from primary TAR is that hardware crosses the ankle joint at the arthrodesis site and when removed, often leaves large bone defects on both the tibial and talar sides, creating concern for adequate bony support for the implants (Fig. 16.5). This concern has further prompted many foot and ankle surgeons to perform ankle arthrodesis with plating via an anterior approach, when consideration is given to potential (eventual) conversion of ankle arthrodesis to TAR7 (Fig. 16.6). Converting an ankle arthrodesis performed with plating via an anterior approach to TAR is relatively straightforward, using the same anterior approach, with direct access to the hardware. Moreover, plating in lieu of screws crossing the arthrodesis site results in minimal compromise to the bone surfaces used to support the TAR implant(s). When multiple large diameter crossing screws were used for ankle arthrodesis, consideration may be given to staging the conversion to TAR several weeks to months after hardware removal with bone grafting in an attempt to allow some bone formation in the bony defects prior to conversion to TAR. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan prior to TAA may be useful to (1) identify distal tibial or talar bone defects that may weaken the support for the implanted components, (2) confirm radiographic suspicion or tibiotalar nonunion, and (3) evaluate the extent of hindfoot arthritis. When hardware is present, we recommend CT scanning with a metal-suppression protocol.

The joint line may be difficult to identify in patients who have undergone ankle arthrodesis, particularly in patients whose ankles progressed to a successful fusion. In contrast, the physiologic joint line is relatively easy to reestablish for nonunions and often following arthroscopic ankle arthrodeses with

minimal bone resection (Fig. 16.7). Planning involves careful analysis of the preoperative radiographs to recreate the natural joint line during surgery (Fig. 16.8). Although some inaccuracies in reestablishing the natural joint line may be compensated by the thickness of polyethylene used, in our experience and that of other investigators, positioning the components as close to the natural level of the ankle optimizes the function of the implant, with optimal bony support, satisfactory balance from residual ligaments (or scar), and best possible dynamic ankle function.2,18

minimal bone resection (Fig. 16.7). Planning involves careful analysis of the preoperative radiographs to recreate the natural joint line during surgery (Fig. 16.8). Although some inaccuracies in reestablishing the natural joint line may be compensated by the thickness of polyethylene used, in our experience and that of other investigators, positioning the components as close to the natural level of the ankle optimizes the function of the implant, with optimal bony support, satisfactory balance from residual ligaments (or scar), and best possible dynamic ankle function.2,18

Figure 16.7. Ankle nonunion after arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Minimal prior bone resection facilitates identifying the joint line for conversion to TAR. |

Probably most crucial is reestablishing the ankle gutters. Although some successful ankle arthrodeses are performed without preparation of the gutters, most fusions include not only the axial weight-bearing surfaces but also the medial and lateral articulations of the talus with the malleoli (Fig. 16.9). These gutters need to be carefully recreated.1,2,18 Furthermore, since the malleoli in ankle arthrodeses are often stress shielded, they are at great risk for fracture. We routinely insert prophylactic screws in the medial and lateral malleoli to protect them from fracture when the ankle joints, particularly the ankle gutters, are recreated2,18 (Fig. 16.10). When we preoperatively template or attempt to predict the size of the ankle components to be inserted, we often plan for the talar component to be one size smaller than the tibial component to ensure that the gutters are adequately prepared. In our experience, all cases require generous gutter debridement after the physiologic gutters have been identified and recreated, typically warranting a talar component that is one size smaller than the tibial component. To recreate the ankle gutters, we use a combination of a small reciprocating saw, a narrow osteotome, and small angled curettes, all of which we plan to have available for the surgery (Fig. 16.11A-C).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree