Conventional Trochanteric Osteotomies and the Trochanteric Slide

Andrew H. Glassman

INTRODUCTION

Sir John Charnley popularized the trochanteric osteotomy for total hip replacement. He considered it an integral component of routine primary arthroplasty for several reasons. These included improved exposure, greater stability against dislocation, and the ability to favorably influence the abductor moment arm ratio (Fig. 4-1). In his words, this permitted the surgeon to perform a true “hip reconstruction” rather than a simple replacement (1,2). Since Charnley’s early writings, the indications for trochanteric osteotomy in primary total hip arthroplasty have evolved and become far more circumscribed. This is attributable to many factors. Significantly, as total hip replacement grew in popularity, the complications of trochanteric osteotomy became apparent (3,4,5,6).

It was soon demonstrated that, in most cases, primary total hip replacement can be successfully and usually more easily accomplished with alternative approaches that leave the trochanter intact. The implants available to Charnley provided limited choices in terms of head/neck length and offset. In addition, early polyethylene technology was limited, leading Charnley to develop and promote the “low-friction arthroplasty” concept, including the use of 22-mm heads. Given these limitations, achieving stability against dislocation and optimizing abductor function were challenging without transfer of the greater trochanter. The development of improved bearing surfaces and thus the ability to use larger heads, a wider range of femoral component choices in terms of their inherent offset and neck/shaft angles, modular heads, and acetabular liners that allow the surgeon to easily fine-tune leg length, offset, and abductor tension have all combined to diminish the biomechanical advantages of trochanteric osteotomy. These technologic advances cannot supplant the superior exposure afforded by trochanteric osteotomy (Fig. 4-2). Thus, in contemporary arthroplasty, trochanteric osteotomy

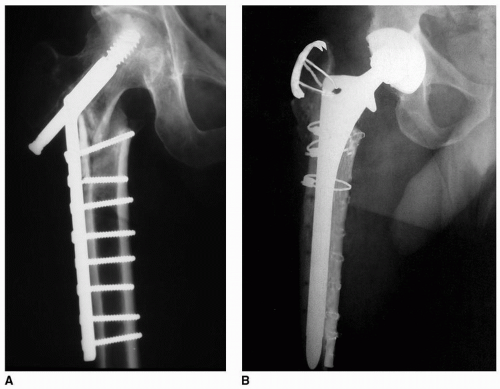

is largely reserved for revision procedures, or difficult primary cases (Tables 4-1 and 4-2) in which wide exposure and/or interface access are desirable (7).

is largely reserved for revision procedures, or difficult primary cases (Tables 4-1 and 4-2) in which wide exposure and/or interface access are desirable (7).

In this chapter, the standard trochanteric osteotomy and a variant, the chevron osteotomy, as well as the sliding trochanteric osteotomy (anterior trochanteric slide) are discussed. Another commonly used variant, the extended trochanteric osteotomy, is discussed in another chapter.

TABLE 4-1 Indications for Trochanteric Osteotomy in Primary THA | ||

|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 4-2 Indications for Trochanteric Osteotomy in Revision THA | |

|---|---|

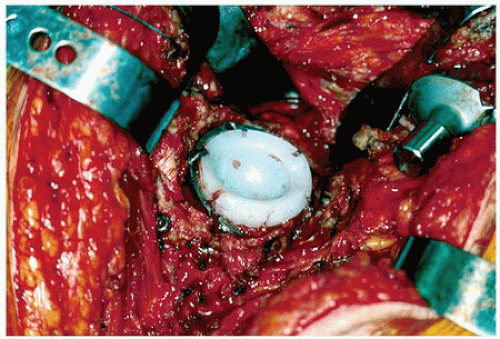

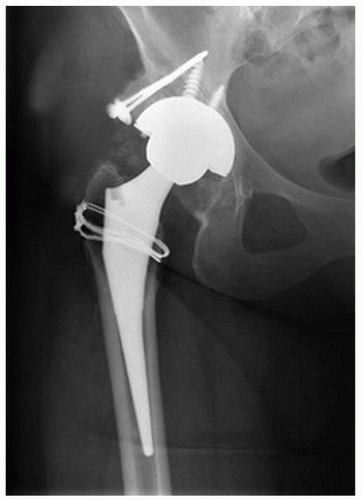

FIGURE 4-3 Crowe II developmental dysplasia treated with femoral head allograft. Exposure facilitated by sliding trochanteric osteotomy. |

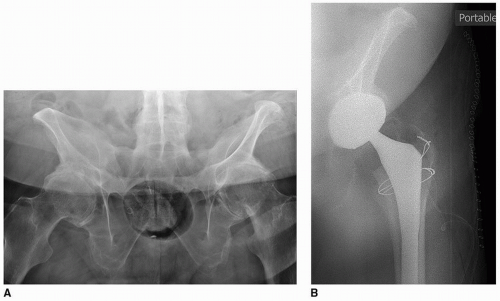

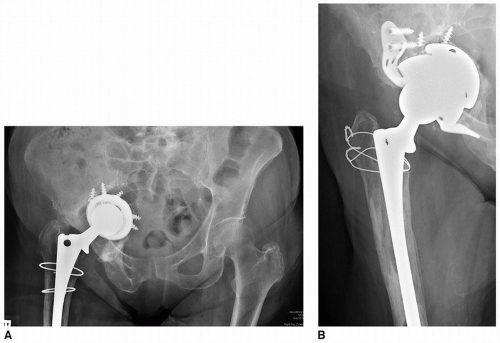

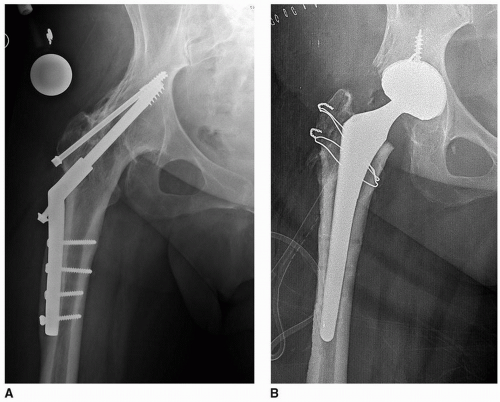

FIGURE 4-5 A: Intra-articular arthrodesis. B: Postconversion of arthrodesis to total hip arthroplasty using sliding trochanteric osteotomy. |

CONVENTIONAL TROCHANTERIC OSTEOTOMY

Surgical Technique (Charnley)

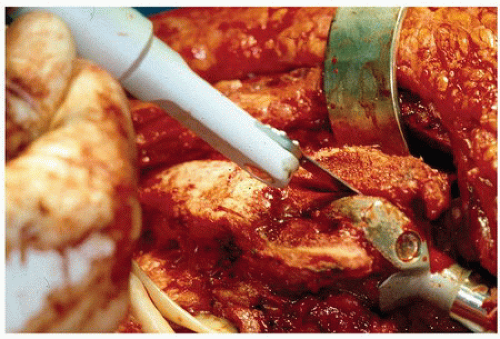

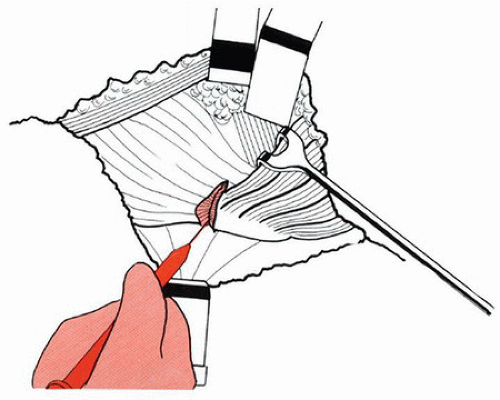

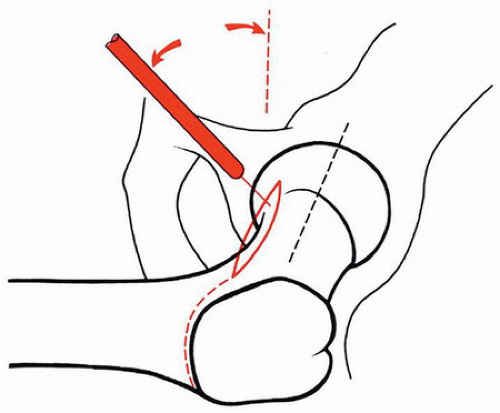

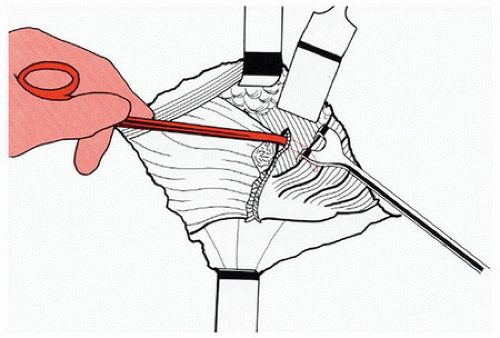

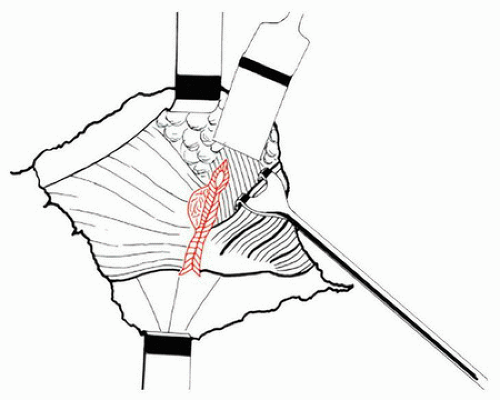

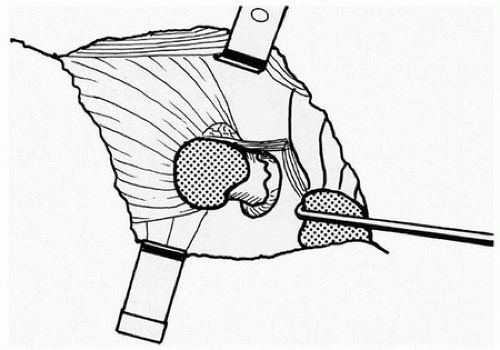

The classic Charnley single-plane osteotomy (1,2,8,9) (Figs. 4-10, 4-11, 4-12, 4-13, 4-14, 4-15, 4-16 and 4-17) begins with exposure of the vastus lateralis ridge by passing a cautery transversely at the summit of the trochanteric ridge. The incision is carried down to the bone, and the ascending branch of the circumflex artery is divided at the distal most extent of the anterior fibers of the gluteus medius. The anterior border of the gluteus medius is retracted cephalad to expose the anterior hip capsule. A horizontal capsulotomy is performed along the anterior aspect of the femoral neck and is extended laterally until it joins the incision made across the vastus ridge. A cholecystectomy clamp is then passed through the capsule and into the joint. The clamp is then maneuvered along the superior aspect of the femoral neck and pulled laterally into the trochanteric fossa. It is then advanced posteriorly to pierce the posterior joint capsule, making certain to pass the clamp medial to the posterior-superior tubercle of

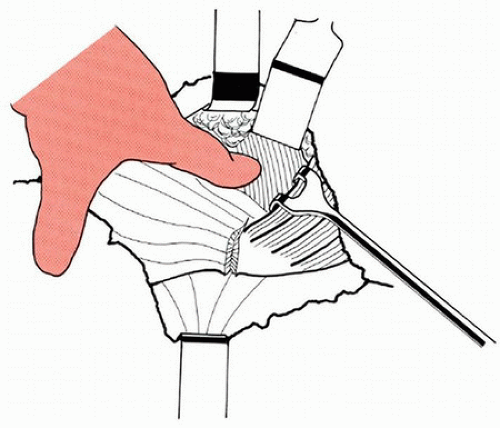

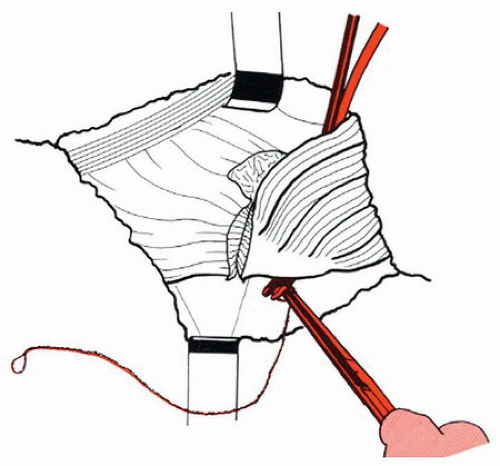

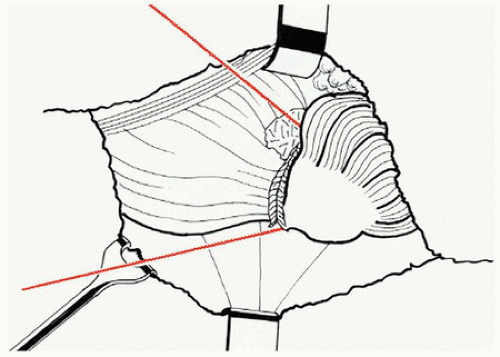

the greater trochanter. Once the tips of the clamp are visualized, it is used to grasp the free end of a Gigli saw that is drawn into the joint and then out of the anterior capsulotomy. Tension is applied to the handles on either end of the saw, and the handles are oriented so as to define a plane that exits through the center of the vastus ridge. The handles are then alternated back and forth to perform the osteotomy. The trochanteric fragment is retracted superiorly. Branches of the anterior and posterior circumflex arteries are ligated or cauterized as needed. The surgeon can then proceed with capsulectomy, dislocation, and arthroplasty.

the greater trochanter. Once the tips of the clamp are visualized, it is used to grasp the free end of a Gigli saw that is drawn into the joint and then out of the anterior capsulotomy. Tension is applied to the handles on either end of the saw, and the handles are oriented so as to define a plane that exits through the center of the vastus ridge. The handles are then alternated back and forth to perform the osteotomy. The trochanteric fragment is retracted superiorly. Branches of the anterior and posterior circumflex arteries are ligated or cauterized as needed. The surgeon can then proceed with capsulectomy, dislocation, and arthroplasty.

FIGURE 4-13 Extension of the capsular incision to the vastus ridge. (From Charnley J. Low friction arthroplasty of the hip: theory and practice. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1979.) |

FIGURE 4-17 The completed osteotomy. (From Charnley J. Low friction arthroplasty of the hip: theory and practice. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1979.) |

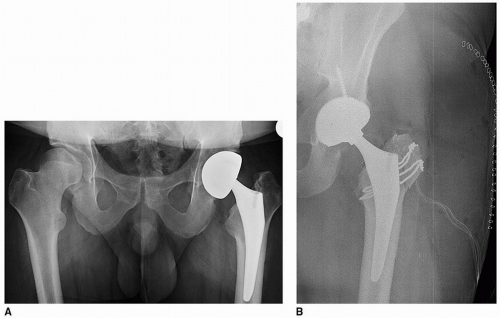

At the conclusion of the arthroplasty, the trochanter can be replaced anatomically, or advanced distally and laterally as much as 1 cm.

Charnley’s fixation technique evolved with time (10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree