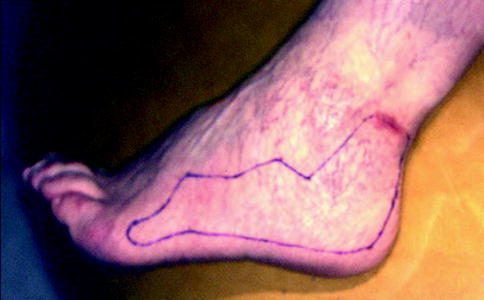

Fig. 17.1

(a) Surgical access to the IAN via lateral cortical window. The drilling procedure places the IAN at risk for iatrogenic injury. (b) Surgical access to the IAN via a buccal corticotomy approach that may also injury the IAN iatrogenically

Fig. 17.2

Mandibular angle fracture sustained following exposure of the IAN via decortication for surgical access, stabilized with monocortical plate and screw fixation

17.2.2 Malocclusion

If the IAN exposure technique involves a sagittal split ramus osteotomy (SSRO), then a malocclusion may result following IAN repair (Fig. 17.3). In addition, a pathologic mandible fracture following IAN repair also carries the risk of malocclusion as well as nonunion or malunion.

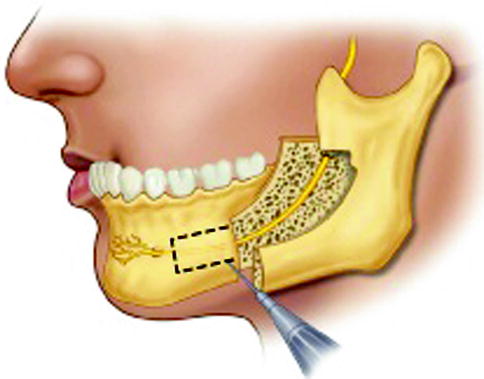

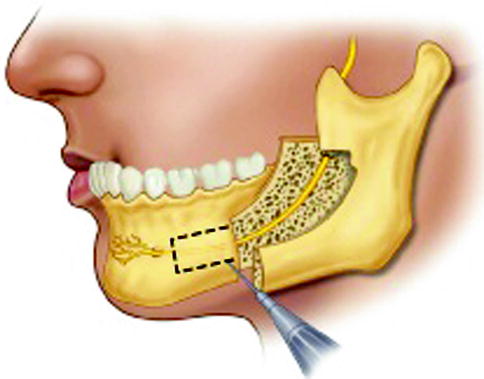

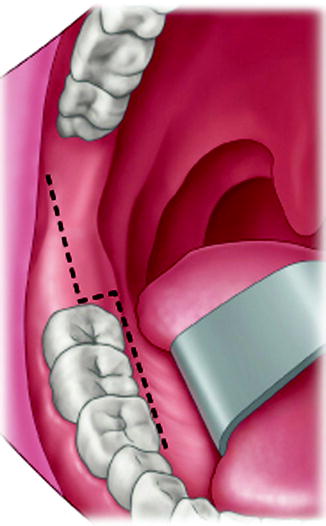

Fig. 17.3

Sagittal split ramus osteotomy approach to the IAN, with possible decortication to the mental foramen for improved IAN mobilization if necessary. This technique has the risk of iatrogenic nerve injury as well as malocclusion

17.2.3 Iatrogenic Nerve Injury

Injury to the IAN or lingual nerve (LN) from an SSRO access is associated with the same complications as an SSRO for orthognathic surgery. Injury to the IAN from the SSRO procedure itself is associated with >80 % immediate postoperative and 0–89.5 % long-term neurosensory impairment. Lingual nerve impairment ranges from 1 to 11.7 % long-term paresthesia. Other complications and concerns associated with the SSRO exposure technique for the IAN include failure of fixation (8 %), bad splits (inadvertent osteotomies), the possible need for postoperative maxillomandibular fixation, and TMJ dysfunction (29 %) [7, 9].

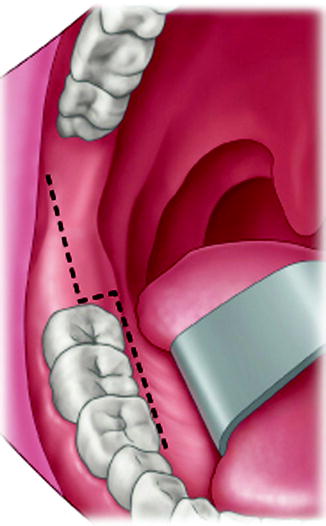

In fact, any surgical approach to the IAN or LN places the nerves at risk for iatrogenic injury. For the LN, the exposure should begin with a lateral distobuccal release from the second molar tooth, and then, the incision should extend into the lingual gingival sulcus of the molar and premolar teeth anteriorly to the canine tooth (Fig. 17.4). While this is a similar incision for third molar surgery so it may place the long buccal nerve at risk for iatrogenic injury, it will help protect the LN from injury from surgical access.

Fig. 17.4

Surgical access to the LN should include a distobuccal releasing incision extending into a lingual gingival sulcus incision to avoid iatrogenic injury to the LN

Any of the access approaches to the IAN place the nerve at risk for iatrogenic injury. Lateral decortication may damage the nerve from direct injury from the bur, so a diamond bur or piezosurgery may be advantageous to minimize this risk. The removal of a block of the lateral cortex of the mandible to expose the IAN widely also places the IAN at risk for injury during the vertical osteotomy cuts, so these should be made only through the cortex and not extend deep into the marrow space. The osteotomy should be completed with osteotomes. Despite attempts to prevent iatrogenic IAN injury, the fact remains that the nerve is certainly at risk during surgical exposure through any of the various osteotomy techniques [4].

17.2.4 Trismus

Due to the location of the IAN and LN for exposure in the posterior region of the oral cavity, surgical access often requires dissection in or around one or more of the muscles of mastication. Trismus due to dissection of the masseter, medial pterygoid, and/or temporalis muscle is not uncommon in the immediate postoperative period. Treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), massage, heat, and physical therapy may be all that is required during the healing process.

17.2.5 Inappropriate Choice of Surgery

It may be possible to perform a nerve resection with neurorrhaphy or nerve graft when decompression or external neurolysis would have been adequate to allow for neural regeneration. The potential for neurosensory recovery is generally better with only decompression or external neurolysis, unless the degree of intraneuronal fibrosis is extensive and prevents axonal migration following release of the nerve from the surrounding tissues. This complication is simply the performance of more surgery than is necessary to accomplish the intended goals. The inexperienced surgeon should consider decompression as a primary treatment option, with a tentative plan to return to the operating room for a more invasive surgical procedure (internal neurolysis or neuroma resection) if neurosensory recovery from the external neurolysis procedure is incomplete.

17.2.6 Transcervical Approach Morbidity

The transcervical approach to the lateral cortex of the mandible for IAN repair is associated with potential additional complications beyond that of a transoral approach. A visible incision scar will always be present to a varying degree and may or may not be acceptable to the patient. In addition, patients who have developed a neuroma from trigeminal nerve injury may be at increased risk for incisional neuropathic pain from the cutaneous nerves. Injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve (VII) may occur due to its location in proximity to the incision and surgical dissection. The decision regarding surgical access depends upon many factors including patient anatomy, patient preference, the site of nerve injury, planned microsurgical procedures, and the surgeon’s skill and experience.

17.2.7 Development of Neuropathic Pain

Surgical repair of the trigeminal nerve following injury is nothing more than a controlled injury to the affected nerve, with careful direct repair or indirect repair. As a result, the same outcomes associated with the initial injury can occur following trigeminal nerve surgery. As discussed elsewhere, failure to achieve significant sensory recovery following surgery is a possibility. The length of time from injury to repair, patient age, and degree of injury influence the likelihood of recovery. A patient with dysesthesia or neuropathic pain may have already developed a central neuropathic pain syndrome prior to an attempted surgical repair, and care must be taken to recognize these patients prior to any surgery, since little to no improvement would be expected. Even complete resection of a large segment of the nerve without any repair or additional methods to prevent neuroma formation (e.g., bone graft between nerve stumps or nerve stump redirection into a muscle) can fail to improve neurosensory function in these patients. Patients without dysesthesia prior to nerve repair surgery can potentially develop painful dysesthesia or allodynia following surgery, and all patients should be made aware of this potential adverse outcome. Of note, the development of dysesthesia following trigeminal nerve repair in a patient without preexisting dysesthesia is an uncommon outcome according to the literature as well as personal experience.

17.3 Donor Site Complications

17.3.1 Sural Nerve Harvest Morbidity

The most common nerve utilized for indirect or gap repair of the trigeminal nerve is the sural nerve or, more appropriately, the medial sural cutaneous nerve. Complications associated with sural nerve graft harvest include paresthesia in the area of the sural nerve distribution, cold or pressure sensitivity, pain, cutaneous scar, and possible disturbance with physical activity involving the ankle (Fig. 17.5) [5]. In a review of outcomes following sural nerve harvest for orthopedic use, at a mean follow-up period of 2 years, there was no area of anesthesia in 50 % of the patients, with a mean area of anesthesia of 12 cm2 and mean area of reduced sensation of 55 cm2. In this study, 25 % of patients were dissatisfied with the appearance and esthetics of the scar [6]. Up to 20 cm of sural nerve graft was harvested by a single longitudinal incision in this series, and this is much more than commonly used for trigeminal nerve repairs. Miloro reported on subjective outcomes following sural nerve harvest specific to trigeminal nerve repair, and in 96 % of subjects, the subjective area of decreased sensation was less than or equal to the size of a quarter dollar, and no subjects experienced pain or cold sensitivity at long-term follow-up. In this study, 15 % stated that there was an effect on their activities of daily living, and 85 % of patients were satisfied with the scar appearance. It must be noted that in this series of patients, one single 5–10 mm transverse incision posterior and just superior to the lateral malleolus was used to harvest nerve segments 2.5–4.0 cm in length (Fig. 17.6) [5].