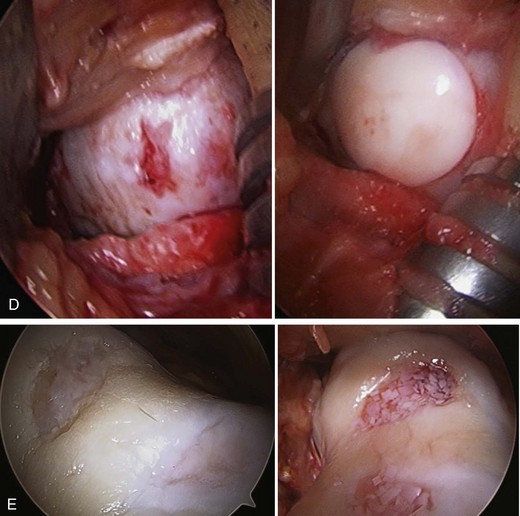

Chapter 68 Patients with knee pain often have coexisting pathoanatomic conditions at the index clinic visit, which may in turn have multiple causes (Box 68-1). With advancements in surgical techniques, available grafts, and imaging modalities, the ability to successfully perform complex cartilage procedures in even the most challenging patient is improving. However, this aforementioned group of patients with multiple coexisting knee pathologies remains a difficult population, especially with regard to determining which (if any) of the lesions is the cause of symptoms. Cartilage lesions may be simply incidental in nature, and the decision to treat is based on their confirmed contribution to a patient’s symptomatology. The combination of malalignment, ligamentous instability, and chondral and meniscal damage presents multiple challenges.1 Corrective procedures for each of these problems performed in isolation have historically produced adequate results; however, combined procedures to treat combined pathologies have proven essential for the success of any single procedure.1,2 Consideration of both patient-specific factors (e.g., age, activity level, expectations) and disease-specific factors is a requisite for treatment planning and optimization of short- and long-term clinical outcomes. Many surgical options are available for the patient with multiple knee pathologies and are often used in combination. Meniscal deficiency can be treated with debridement, direct repair, or meniscal allograft transplantation. Ligamentous pathology can be addressed with direct repair or reconstruction depending on the region of injury. Articular cartilage pathology can be addressed with a variety of procedures including debridement, microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), and osteochondral autograft or allograft. Finally, medial compartment disease with varus malalignment can be addressed with a high tibial osteotomy (HTO) that unloads the diseased medial compartment, and lateral compartment disease with valgus malalignment can be treated with a distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) that unloads the lateral compartment. More recently, HTO has been used as a concomitant malalignment corrective procedure in patients undergoing cartilage and/or meniscus surgery in an attempt to offload the compartment in which cartilage surgery is performed.1–4 A recent systematic review performed by Harris and colleagues2 analyzed clinical outcomes in patients undergoing combined meniscal allograft transplantation and cartilage repair or restoration. Of the six studies included, 110 patients were identified as having undergone meniscal allograft transplantation and either ACI (n = 73), osteochondral allograft transplantation (n = 20), or osteochondral autograft transplantation (n = 17). In addition, three patients underwent concomitant microfracture. Of note, 33% of patients (36 of 110) underwent other concomitant procedures including HTO or DFO, ligament reconstruction, and/or hardware removal. The authors noted improved outcomes in combined procedures compared with isolated surgery in four of the six studies. Overall, 12% of patients experienced failure of their combined procedure that necessitated revision surgery, and 85% of these failures were noted to be related to the meniscus procedure as opposed to the cartilage procedure.2 In a knee with multiple pathologies (meniscal deficiency, chondral defect, malalignment, and ligament instability), each entity must be considered individually with respect to its influence on the overall status of the knee. Meniscectomy is a commonly performed procedure in sports medicine. It is minimally invasive and can produce satisfactory outcomes in a majority of patients, especially those desiring a quick return to activity. However, the procedure is not without risks when it comes to the long-term health of the knee. Subtotal meniscectomy decreases joint contact area5 and increases peak stress.5 After subtotal or total meniscectomy, there is a fourteenfold increased relative risk of developing unicompartmental arthritis.6–8 Furthermore, multiple studies have demonstrated worse outcomes associated with young age, chondral damage found at time of menisectomy,9,10 ligamentous instability,11–13 and/or tibiofemoral malalignment. In addition, meniscal repair as well as meniscal transplantation have less favorable outcomes when performed with untreated concomitant instability, malalignment, and/or articular cartilage disease.1,4,14–16 Thus, although addressing multiple coexisting pathologies in a single patient’s knee is certainly challenging, neglecting to correct concomitant comorbidity can compromise overall results and in the worst case scenario lead to a uncorrectable salvage situation. Damage to the articular cartilage occurs for a variety of reasons, including mechanical overload, developmental defects, genetic failures, and traumatic impact. Articular cartilage injury leads to an increase in degenerative joint disease, especially with bipolar “kissing” lesions. Full-thickness chondral injuries can be extremely problematic, causing knee swelling, pain at night and with rest, and severe activity-related pain.17,18 Furthermore, it is necessary to determine if a chondral lesion has any underlying subchondral bone changes because this feature would affect decision making in the perioperative period. Knee malalignment causes excessive loading of articular cartilage, which can lead to degenerative joint disease. The mechanical axis (center of femoral head to intercondylar eminence to center of ankle) of the leg is different from the weight-bearing axis (center of femoral head to center of ankle). Because the anatomic axis of the femur differs from the mechanical axis, the normal anatomic weight-bearing axis of the knee is approximately 5 to 7 degrees of valgus. Furthermore, in a normal knee approximately 60% of the weight-bearing force is transmitted through the medial compartment. Varus malalignment19 shifts the center of the knee joint lateral to the mechanical axis, leading to medial tibial cartilage volume and thickness loss, as well as increases in tibial and femoral denuded bone.19 Valgus malalignment shifts the center of the knee medial to the mechanical axis, leading to increased, unbalanced lateral-sided forces. Osteotomy procedures (HTO, DFO) alter the biomechanical axis by shifting load away from the damaged compartment. The pathophysiologic principle of this procedure is to correct the weight-bearing axis if possible to avoid rapid and irreversible progression of unicompartmental degenerative joint disease.20–22 Patients with complex, combined knee pathologies typically report unilateral, single compartment knee pain. Often their symptoms are chronic in nature, because it takes time for any one of these isolated injuries to have an additive effect on another. This goes to the core of the complexity of treating patients with multiple knee pathologies. Diagnosing and treating any injury occurring in isolation is usually rather straightforward; however, multiple concurrent injuries tend to expedite the development of degenerative disease. Therefore these patients may also be seen after at least one, if not more, previous (and unsuccessful) surgical intervention. Only occasionally are these types of patients seen acutely after a traumatic event. Other common components of the patient presentation are outlined in Table 68-1. TABLE 68-1 • Active and passive range of motion • Hamstring flexibility and iliotibial band assessment (Ober test) • Tests of stability and special tests – Pivot shift, Lachman, anterior drawer – Varus and valgus stress (at full extension and at 30 degrees of flexion) – Anteromedial rotary instability: should be assessed with the knee in 90 degrees of flexion with the patient supine – Posterolateral rotary instability: should be assessed with the patient prone while external rotation is applied to both knees in 30 and 90 degrees of flexion for side-to-side comparison Imaging for patients with combined knee pathologies can include the following: – Standard weight-bearing radiographic series (anteroposterior [AP], lateral, Merchant) – Weight-bearing double-stance long-leg axis series – Sizing radiographs (for meniscus transplantation and osteochondral allograft transplantation candidates) (Fig. 68-1) • Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Complex Problems in Knee Articular Cartilage

Pathophysiology

Preoperative Considerations

Symptom

Condition in Which Symptom Is Common

Intermittent pain (“comes and goes”)

Articular cartilage injury, malalignment

Swelling, rest pain

Articular cartilage injury, malalignment

Mechanical symptoms (clicking, locking)

Meniscus injury

Joint line pain and tenderness to palpation

Meniscus, articular cartilage, ligament injury

Sensation of instability

Ligament injury, meniscus injury

Multiligament injury

Ligament injury

Physical Examination

Imaging

Weight-bearing AP views in extension

Weight-bearing AP views in extension

Weight-bearing posteroanterior (PA) views in 45 degrees of flexion

Weight-bearing posteroanterior (PA) views in 45 degrees of flexion

Standing bilateral 45-degree flexion PA view of knee with the x-ray tube directed at 10 degrees caudal. The 10-cm marker should be placed on the lateral aspect of the affected knee at the level of the joint space.

Standing bilateral 45-degree flexion PA view of knee with the x-ray tube directed at 10 degrees caudal. The 10-cm marker should be placed on the lateral aspect of the affected knee at the level of the joint space.

Lateral non–weight-bearing knee view. The 10-cm marker should be placed next to the knee cap at the level of the joint space.

Lateral non–weight-bearing knee view. The 10-cm marker should be placed next to the knee cap at the level of the joint space.

Complex Problems in Knee Articular Cartilage