Common Sports-Related Injuries and Illnesses: Generic Conditions

Douglas B. McKeag

The philosophies of care given here are meant to serve as “ground rules.” We will refer to these protocols in discussing specific injuries. The general conditions covered are as follows:

Acute injury

Chronic injury (with emphasis on overuse syndromes)

Allergy

Acute Injury

Acute injury is the most common sports medicine condition; unfortunately, it is also the one most likely to be ignored. Injuries that require attention on the playing field are rare in comparison to the number of acute injuries incurred in less formal contests. Beyond the initial involuntary rest (usually temporary, whether symptoms have disappeared or not), the only other attention that might be given to an acute injury is the application of a pressure dressing (elastic bandage) and/or hot/cold therapy. Little else is done, and rarely is medical attention sought. Most athletic injuries do not occur in competition but in practice or unobserved, unsupervised surroundings. Granted that most acute injuries are not true medical emergencies, but they can be treated easily if proper diagnosis is made. The untoward effects of any athletic injury can be minimized by proper care, especially in the first 24-hour postinjury period.

Coverage of athletic competition and/or practice is discussed in Chapter 9.; however, the following guidelines apply to the care of any acute injury.

Become familiar with the frequency level of common injuries in the sport you are covering and in the community you live in. Of the multiple factors that determine injury frequency, the two with the greatest effect are the local community environment and the specific position played by an athlete. Sports and exercise produce more than a fair share of “zebras,” but for the most part we still see and care mostly for the “horses”: expect them, and learn to take care of them.

There is no single true philosophy in primary care sports medicine, only guidelines. Those guidelines should reflect individual community situations. The following mind-set for covering a sports event works well in any community regardless of the situation, geography, or personnel involved:

before competition: prevention;

during competition: triage;

after competition: rehabilitation.

Someone who understands and accepts this philosophy is the best person to be responsible for the care of competitors in a sports event in your community. Contrary to what some may think, this does not require compromising any principles of medicine. Athletes are no different from nonathletes where health care is concerned. Where

the groups diverge is with respect to exercise-induced injury. Athletes are in an environment that exposes them to acute macrotrauma as well as chronic microtrauma. In that environment the athletes will suffer more injury than the nonathletes.

the groups diverge is with respect to exercise-induced injury. Athletes are in an environment that exposes them to acute macrotrauma as well as chronic microtrauma. In that environment the athletes will suffer more injury than the nonathletes.

Before Competition

Active intervention in the precompetitive aspects of any community sports system offers the greatest opportunity for significant injury prevention. The preparticipation screening and assessment of the sports environment are two major areas of preventive impact.

During Competition

One of the most uncomfortable and disquieting moments a team physician can have is when he must make sideline decisions while under the close scrutiny of many spectators. However, 67% of all injuries occur during practices or training, a time when the physician is unlikely to be present. The situations are different, but these are the norms in covering athletic teams and it underlines the need to have established protocols for triage in place. Coaches, trainers, and other responsible parties need to learn appropriate triage techniques for the more common injuries. Even when the physician is present, his/her major responsibility is the triage of the acutely injured athlete.

A decision on whether to allow the participant to resume play should be made only when (a) a definite diagnosis has been made, (b) the injury will not worsen with continued play so that the athlete is at no greater risk of further injury, and (c) the athlete can still compete fairly and is not incapable of protecting him/her because of the injury. See Table 23.1 for a list of injuries that preclude further participation. This table may seem conservative at first; please reread it. It is less conservative than most lists and can be helpful in assessing the most common athletic injuries in youngsters. With college-aged or professional athletes, this apparent conservatism can be addressed on an individual basis if the physician finds it necessary to move outside these vaguely defined boundaries. The best philosophy for evaluating acute athletic injuries on-site should be neither excessively conservative nor dangerously liberal. The final decision on return to competition should always be that of the physician.

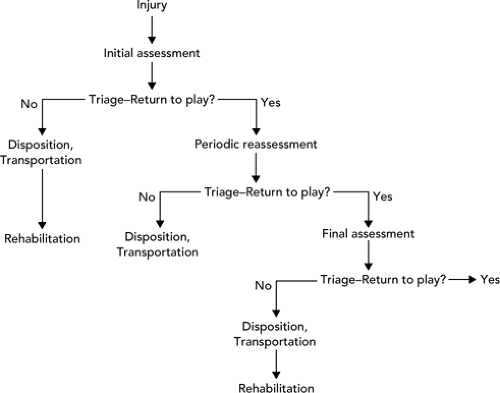

Generally speaking, the evaluation of all acute injuries that occur in competition should follow the same steps (see Figure 23.1). Immediate initial assessment is mandatory and will help elicit signs and symptoms before the inevitable secondary reactions (pain, swelling, inflammation, spasm, decreased range of motion, and guarding). First, observe the position of the athlete and the injured part in relation to the rest of the body. Begin the history with the patient’s account of how the injury occurred and amplify it with the physician’s assessment of the biomechanics of the situation, as well as that of others who may have witnessed the injury occur (trainer, coach, teammate, or official). Determine any positive past medical history from available records if they exist. Next should be a focused clinical appraisal of the injury; that is, an examination emphasizing function, range of motion, and the neurological and vascular integrity of the injured area.

TABLE 23.1 Situations Precluding Return to Participation in Competitive Sports Following an Injury | ||

|---|---|---|

|

With serious injuries, a protocol is implemented that addresses whether to treat the injured player at the site or take him/her to a medical facility. If he/she is unable to walk safely, then a decision must be made on how to transport the athlete.

With less serious injuries, the first decision is whether to allow the athlete to continue to participate. Even if the decision is affirmative, he/she should be periodically rechecked. The interval between checks will depend on the severity and rapidity of evolving symptoms. Any athlete with an evolving injury in which signs and symptoms are changing must be watched and not left alone. If an athlete leaves the sideline, he/she should be accompanied by someone who is aware of the significance of the changing symptoms of the injury. Subsequent assessment on the sidelines or in the locker room should include the same components: observation, history, and re-examination. Clothing and equipment should be removed whenever possible. A later examination should focus not only on the injured area, but also above and below the area surrounding the injury. An

appraisal of how the signs and symptoms have progressed since the first examination should also be made.

appraisal of how the signs and symptoms have progressed since the first examination should also be made.

If an athlete is allowed to return to play and sustains a recurrence or exacerbation of the injury, he/she must be withdrawn from play for the remainder of the contest. If the athlete is not allowed to return, periodic assessments should continue and initial treatment and/or transportation begun.

After Competition

After a diagnosis is established and appropriate treatment given, rehabilitation can be considered and a multidisciplinary team approach involving the team physician, athlete’s personal physician, other consultants (if necessary), trainer, and coach should be initiated. In reality, such a coordinated effort rarely happens. Statistics in West Virginia (2) revealed that a physician saw only 13.5% of acute injuries from a system at the high school level within 24 hours, which is the period when evaluation and treatment are the most productive. Although this low figure has hopefully increased over the past 30 years, the problems of physician accessibility remain significant. Even so, proper rehabilitation is the most important factor in the rapid return of an injured athlete to participation sports (see Chapter 35).

Common Acute Injuries by Type

One of the best and most useful surveys on sports injuries was conducted by Garrick and Requa (3). Although it dealt only with the high school level, it broke down sports injuries by type and provided a guideline on what to expect for the common acute sports injury. The numbers in parenthesis in the following text are from this study.

1. Sprains and strains (60.5%)—There are two ways that most sprains and strains develop. The common etiology is a sudden, abrupt, violent extension or contraction on an overloaded, unprepared, or undeveloped ligament or musculotendinous unit. There can be varying degrees of severity, from the overstretching of a few myofibrils to complete unit rupture. A second, less common, mechanism involves chronic stress placed upon the unit over time, in association with poor technique, overuse, or deformity. Strains are stretch injuries to the musculotendinous unit; sprains involve similar injury to ligamentous structures. A grading system is used to assess these injuries.

First degree/grade 1. There is little tissue injury and no increase in laxity. There usually is little immediate swelling because the tissues have not been stretched enough to produce instantaneous hemorrhage. With strains, there is usually no significant damage to the muscle or tendon and only a brief period of pain and disability if it is properly treated. Secondary tissue edema and inflammation develop within hours, restricting range of motion and resulting in minimal loss of function. Pathologically, less than 25% of the tendinous or ligamentous fibers are involved in a first-degree sprain or strain.

Second degree/grade 2. These injuries are the result of tears and disruptions of ligament or tendons. The partial tearing ranges from 25% to 75% of the fibers and there is demonstrable laxity and loss of function. There is immediate swelling and

function is significantly reduced. Signs and symptoms increase until bleeding is controlled and the injury immobilized.

Third degree/grade 3. Complete disruption of the ligament or tendon usually exists with immediate pain, disability, and loss of function. However, some third-degree sprains may actually be less painful than second-degree sprains. Once a ligament is torn, there is no further stretch to cause pain sensation. Third-degree strains usually have diffuse bleeding and continuous pain.

The treatment of a third-degree injury (ligament or tendon rupture) continues to undergo change. With proper immediate care, including immobilization, these injuries can be treated conservatively without surgical intervention. Common examples of this type of injury include the medial collateral ligament in the knee, the lateral supporting structures of the ankle, and clavicular ligaments of the shoulder. Ligaments or tendons that normally are under a high amount of natural stress (Achilles tendon, biceps tendon, and the patellar ligament), as well as tendons that have retracted or ruptured, require prompt surgical intervention. Occasionally, when the tear is at the musculotendinous junction (such as an Achilles ligament rupture), the preferred treatment is immobilization. Bear in mind that severe strains and sprains may cause fewer symptoms and signs than the more moderate ones. Many young athletes have natural ligamentous laxity. Always examine and compare the injured and uninjured sides to help resolve those cases in which the findings appear equivocal.

Frequent sites of sprain are ankles (anterior talofibular ligament), knee (medial collateral ligament), and fingers (intrinsic collateral and interphalangeal ligaments). Frequent sites of strains are upper leg (hamstring muscles and adductors), back (paraspinal muscles), and the shoulder (rotator cuff tendons).

The following modalities (RICE regimen) are useful in treating strains and sprains:

R—rest the injured part to allow healing to begin and prevent further injury.

I—apply ice to the injured part to reduce swelling and extravasation of blood into the tissue (the ice should be applied directly to the skin as a massage unit at frequent intervals, but not to exceed 10 to 15 minutes per session).

C—compression with an elastic bandage, air splint, and so on, to prevent movement and further swelling.

E—elevate the injured area whenever possible to prevent pooling of blood and to control swelling.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree