Common Injuries from Running: Introduction

Approximately 11 million people in the United States run more than 100 days per year. Recreational exercise is attractive because it improves the quality of life and increases longevity. Runners note a range of salutary effects, from improved cardiopulmonary capacity to enhanced mental health, less depression and anxiety, and a greater sense of tranquility.

Regular exercise enhances sleep patterns; promotes a stronger and more stable musculoskeletal system; and results in decreases in disability, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, stroke, and osteoporosis. Runners report increased appetite and healthier weight, a desirable combination. Except for walking, running may be the most easily accessible and least expensive form of regular exercise.

However, there are important health concerns that develop as a consequence of running as well. These include the risk of sudden death, musculoskeletal injuries, and potentially deleterious effects on joints. Approximately 45–70% of runners will experience musculoskeletal injuries each year.

Repetitive use, rather than a single traumatic event, causes the majority of running injuries. Table 72–1 lists the 10 most common injuries seen in one clinic and is representative of reports from other large series. Risk factors for running injuries include history of a previous injury, competitive running, high weekly mileage (>25 miles per week), and abrupt increases in the intensity or duration of training. Injuries are more likely to occur when the runner’s shoes are worn down, leading to the recommendation that shoes be replaced every 6 months or after 400 miles of use.

| Medical Diagnosis | Percentage | n |

|---|---|---|

| Patellar pain syndrome | 25.8 | 468 |

| Stress fractures | 13.2 | 239 |

| Achilles tendinitis | 6.0 | 109 |

| Plantar fasciitis | 4.7 | 85 |

| Patellar tendinitis | 4.5 | 81 |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | 4.3 | 78 |

| Metatarsalgia | 3.2 | 58 |

| Tibial stress syndrome | 2.6 | 47 |

| Tibialis posterior tendinitis | 2.5 | 45 |

| Peroneus tendinitis | 1.9 | 34 |

| Total | 68.7 | 1224 |

Stretching is of particular interest because runners frequently report performing better and feeling better after stretching. However, a large controlled trial of stretching as taught by an Olympic marathon coach showed no difference in injury type or frequency between the intervention and control groups. Thus, the well-entrenched lore of stretching and running does not have evidence-based support. Similarly, there is little or no evidence to support proposed links between running injuries and age, gender, body mass, hill running, running on hard surfaces, time of year, and time of day.

The physical examination of an injured runner should not only focus on the area of pain but should also include an examination of adjacent joints, alignment, and flexibility. Approximately 20–40% of running injuries can be related to structural abnormalities. The foot must dissipate 110 tons of force for every mile run, and alignment abnormalities of the foot are associated with increased frequency of injury. A high-arched foot (pes cavus) is rigid and tends to transmit impact up the leg. A flat foot (pes planus) leads to excessive pronation of the foot during running, which in turn increases stress on the medial structures of the ankle, shin, and knee. Orthotics may be helpful for either type of structural abnormality.

Hamstring and calf flexibility can be assessed with the runner in the supine position on the examining table, the femur at 90 degrees to the table, and the foot at 90 degrees to the tibia. The physician should be able to passively extend the knee to within 15 degrees of full extension. Although there is little evidence that stretching prevents running injuries, stretching may be of therapeutic value for the injured runner with limited flexibility.

The athletic shoe industry is a $13 billion-per-year industry that sells more than 350 million pairs of shoes annually. Sports shoes, particularly running shoes, have penetrated into every facet of mainstream America. They have become a fashion statement, and even convey some of us to work. Consequently, the use of athletic shoes for casual and fashion wear has had a large influence on their appearance and features. Fortunately, podiatric biomechanical thought and technology have sunk deeply into the psyche of the industry and buying public. Terms such as pronation, stability, and motion control are now widely used in the description and rankings of running shoes.

Today’s running shoes are designed with an eye toward accommodating various types and shapes of feet. Shoes are made that allow for differences between men and women, light-and heavyweight runners, pronated and supinated (under-pronated) feet, and narrow and wide feet. Increasingly sports-specific shoes meet the diverse needs of different sports, and even different running conditions such as trail running and racing on various surfaces.

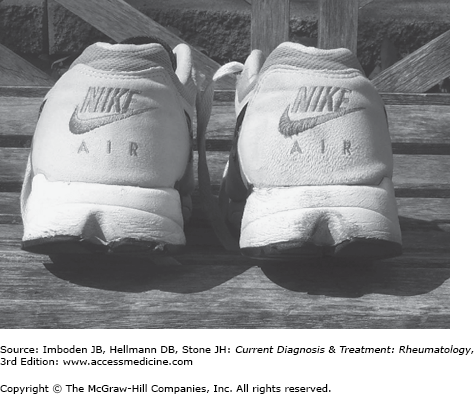

Evaluation of an injured runner should always include examination of a well-used pair of running shoes, so patients coming to a new visit should be advised to bring a pair with them as part of the evaluation. Most important is to examine shoe tilt by looking at shoes from the rear at eye level. Do not pay attention to the heel or outsole wear, but rather look at the angle of the upper (the top part of the shoe that the foot fits into) relative to perpendicular. If the upper is tilting, bent or smashed toward the inside of the foot, overpronation is occurring (Figure 72–1). If the upper has no tilt, the biomechanics are normal or neutral. Finally, if the upper is tilting or bent toward the outside of the foot, the biomechanics are those of supination, also known as underpronation.

Current thinking is that runners with excessive pronation need a shoe that has more rearfoot control but can have a bit less shock absorption. These shoes are described as “motion control” shoes, and employ dual-density midsoles and medial posts to control excessive pronation. Neutral runners can use a shoe without this technology, saving both cost and weight. These are referred to, somewhat confusingly, as “stability” shoes. People with a high-arched (cavus) foot need more cushioning because of the rigid nature of their foot. These are more obviously referred to as “cushioned” shoes. Some general principles of shoe fitting for all running athletes are outlined in Table 72–2.

|