ELICITING NEGATIVE AUTOMATIC THOUGHTS

Anxiety is accompanied by different types of thought, and it is necessary to distinguish between types of thought in correctly targeting NATs. For more information on this differentiation refer to Chapter 1. For present purposes, it is important to distinguish between primary NATs and secondary thoughts in anxiety. Secondary thoughts concern themes of escape, avoidance and neutralisation of danger, whereas primary NATs concern themes of danger. For example, when asked ‘What thought did you have when you felt anxious?’ a social phobic could answer ‘I thought I’d better not say much’. Clearly this is not a danger-related cognition but represents a secondary response to some primary and implicit NAT. Other examples of secondary thoughts include: ‘I just wanted to escape; I didn’t want to be there; I had to get out; I must get a drink.’ To elicit a primary NAT, questions should be directed at elucidating the consequences of not engaging in coping or avoidance responses. In the example of the NAT ‘I thought I’d better not say much’, follow-up probe questions like the following could be used: ‘If you did say things, what’s the worst that could happen?’ or in cases where thoughts concern escape and avoidance the probe question ‘What’s the worst that could happen if you were unable to leave the situation?’ could be used. Some thoughts articulated by patients are neither primary NATs or secondary thoughts, but are what we might call surface thoughts. An example of a surface thought in panic disorder is: ‘I thought I was going to panic.’ The thought is representative of a primary NAT but the precise nature of the danger is obscure. In order to determine the primary NAT the meaning of the thought should be determined (e.g. ‘What’s the worst that could happen if you panicked in the situation?’ or ‘What does having a panic attack mean to you?’).

In summary, NATs can be distinguished from other forms of anxious thought such as obsessions and worries (see Chapter 1). In the conceptualisation of problems of intrusive thoughts (i.e. chronic worry and obsessions) it is the NAT or negative appraisal of the obsession or worry that is of central significance. In treating anxiety disorders it is necessary to ensure that the focus of conceptualisation and intervention is directed at relevant NATs. Primary NATs should be distinguished from secondary coping-related appraisals, or surface thoughts. Some NATs are implicit and occur as ‘silent’ thoughts, which are accessible by exploring the consequences of not coping, not escaping, and not avoiding situations, or by asking about the worst consequences in a situation. With this distinction in mind we now consider ten methods for accessing NATs.

Ten ways of eliciting relevant NATs

Worst consequences scenario

One of the most effective questions for eliciting NATs in the therapeutic dialogue is ‘What’s the worst that could happen if . . . ’? This question stem can be completed with a number of different items depending on the context in which it is used. It is advisable that the therapist seeks the worst consequences scenario in response to more general negative appraisals. We saw earlier in this chapter how a combination of questions targeted at worst scenarios and questions focused on determining meanings can be used to elicit primary NATs. The technique is illustrated in the following example of social phobia:

In this example the patient was initially unaware of negative thoughts in recounting the situation. However, by questioning for worst consequences, a key negative automatic thought was elicited: ‘They’ll think I’m boring and stupid.’ Notice that the therapist followed up elicitation of the thought with a question to check the validity of the NAT in the patient’s case: ‘When you were in the group were you aware of thinking that?’

Re-counting specific episodes

Recent occurrences of anxiety, such as panic attacks or worry episodes, can be discussed in detail to elicit negative automatic thoughts and appraisals. Typically, it is most efficient to select a concrete recent and specific episode rather than focusing the review on episodes in general. Initial aspects of the review focus on a description of the situation in which anxiety occurred or the events leading to anxiety or particular symptoms. The individual’s appraisals of these events is elicited, and the emotional reaction accompanying such appraisals is sought. Emotional reactions are often determined first, and then NATs accompanying emotion are often more accessible. The following example demonstrates the use of this technique in a patient with agoraphobia.

In this example, the patient reports a period of anticipatory anxiety before entering a public situation. The NATs for this period are obscure in the patient’s account. The therapist pursues the scenario anticipating that specific NATs will become evident as the situational account unfolds. As anxiety increased in the account of the situation, this is used to signal questioning of thought content. At this juncture the patient reports secondary cognitions pertaining to the desire to leave the situation. In order to determine the NATs behind the secondary (escape / avoidance) cognitions the therapist asks whether anything bad could happen. This produces the NAT, ‘My legs would give way, and I’d collapse’. The therapist asks for a belief rating of the NAT—a high rating can signify the importance of the thought in anxiety, and the rating should be tracked through the reattribution process as a marker of treatment effectiveness.

When negative automatic thoughts are not immediately evident, elicitation of the types of emotion experienced in situations and a description of emotional symptoms can prime negative automatic thoughts and make them more amenable to introspection.

The use of specific sequences of questions in the recounting of recent emotional episodes is the basis for constructing idiosyncratic vicious circle formulations as in the conceptualisation and treatment of panic disorder, to be discussed in Chapter 5. However, in some instances, particularly when avoidance is extensive, an individual is unable to remember and report a recent anxious situation. In these circumstances, other techniques like those discussed below may be used to elicit negative automatic thoughts.

Affect shifts

An affect shift is a change in emotion. Changes should be monitored during the course of a treatment session and are indicative of the activation of negative automatic thoughts. When an affect shift is detected by the therapist, the presence of emotion is acknowledged first, this may then be followed by asking the patient to describe the feeling experienced (this can be used to intensify awareness of the affective experience), and then attempts are made to elicit the content of thought associated with the emotion. The following extract illustrates the use of an affect shift to elicit salient negative automatic thoughts.

Changes in affect can occur during discussion of symptoms and emotion, and also occur in the context of exposure experiments and induction of symptoms. In these circumstances questions can be used to elicit the content of thought. In some cases the therapist is able to direct the line of conversation in such a way that affect shifts are more likely. Unfortunately, there may be a tendency for some patients to direct the course of conversation in the opposite direction in an attempt to produce sessions that are affect-free. Cognitive affective avoidance of this type is often marked by a tendency to discuss situations in fine detail combined with a seeming inability to give direct answers to the therapist’s questions. It should be noted, however, that such attention to detail may be a characteristic of the individual’s personality rather than situation-specific emotional avoidance.

Dysfunctional Thoughts Records (DTRs)

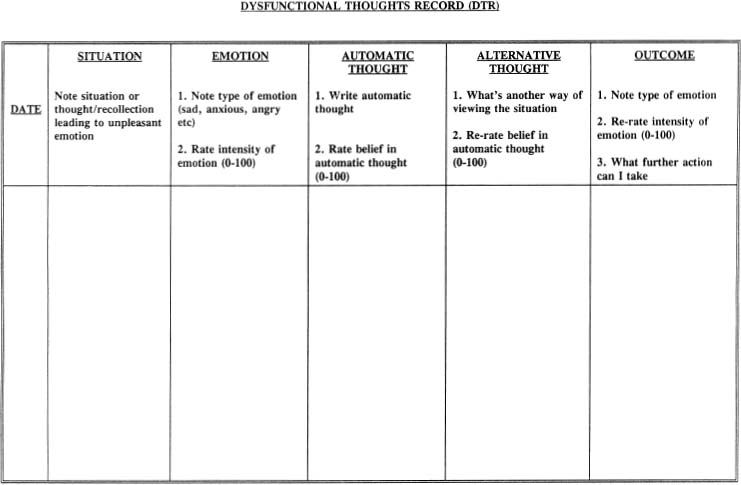

Dysfunctional thought records take different forms. The general standard form of a DTR is presented in Figure 4.0.

Figure 4.0 Dysfunctional Thoughts Record (DTR)

DTRs are used for a number of purposes. Early in treatment they provide a means of recording negative automatic thoughts associated with emotional change. In this respect they provide information concerning the content of negative automatic thoughts and they offer a means by which the individual can develop an awareness of the links between thoughts and feelings. Thought records and diary measures also provide information on symptom patterns. The existence of patterns in symptoms can be used in some circumstances to strengthen the cognitive formulation of emotional problems, and in the case of health anxiety to falsify the patient’s physical illness model. Disorder-specific DTRs should be used when negative automatic thoughts are associated with specific identifiable bodily sensations or other specific stimuli. In the treatment of panic disorder for example, a DTR might consist of additional columns for recording a range of bodily sensations and then a column for recording the negative misinterpretation of these sensations. Disorder-specific cognitive models can be used to develop DTRs that assess the salient NATs implicated by these models. In obsessive-compulsive disorder for example, in which the cognitive model specifies that the negative appraisal of intrusive thoughts is important, the DTR should consist of columns for monitoring intrusive thoughts and columns for noting the negative interpretation of the intrusive thought or NAT (see Chapter 9 for more details). The cognitive model of social phobia predicts that negative self-evaluation is as important as fear of negative evaluation by others in problem maintenance. Therefore, DTRs may consist of columns for recording negative automatic thoughts about the self and for recording negative automatic thoughts concerning other people’s evaluation of the self in anxiety-provoking situations.

Exposure tasks

Exposure is used as a means of activating fear. Patients may be exposed to analogue stressful situations or real-life situations. Access to salient NATs may be restricted when the individual’s ‘fear mode’ is inactive. In these circumstances it is useful to activate the patients’ fear in order to increase accessibility of NATs. The effect of ‘fear mode’ activation on NATs is evident in patient’s reports of the believability of negative appraisal. For instance, social phobics believe highly that they are the centre of other people’s negative attention when in social situations. However, when questioned away from the situation the level of belief is often diminished. Similarly, panic patients report strong beliefs in catastrophe during panic attacks but are able to question the validity of their belief when not panicking. Exposure exercises provide a mechanism for accessing situationally moderated NATs. Moreover, when avoidance is extensive the reversal of avoidance facilitates access to otherwise inaccessible dysfunctional appraisals. In the following therapy excerpt, the therapist accompanies an agoraphobic patient on a exposure expedition to a normally avoided shopping centre. Initial attempts to determine the content of the patient’s NATs in the consulting room were unsuccessful, and it was decided to explore the thoughts elicited by exposure to a feared situation. The example illustrates the types of questions that can be used to determine primary NATs.

In this example, the patient’s fears concerning negative evaluation by others became clear on exposure to a feared situation. Apart from the information presented in this excerpt, the therapist followed through with the exposure task in order to determine the patient’s subtle safety behaviours used during the situation. The information gained was used in building an initial formulation of the patient’s problem.

Role-plays

Role-plays are a useful form of exposure-based exercise in cases of social anxiety. An advantage of role-plays over real-life exposure is that the variables in some role-plays can be manipulated and controlled more efficiently than real-life social circumstances. This allows for the modulation of social factors in a way that increases fear activation and the accessibility of NATs. In social phobia, for example, the predominant fear may be of one-to-one interactions involving self-disclosure. Analogue situations of this type can be created through role-plays with the therapist. During such role-plays the patient is asked to monitor his / her level of anxiety and to signal an increase in anxiety or distress to the therapist. At this point, the role-play is halted and discussion is focused on the NAT’s accompanying anxiety. Dimensions of the role-play can be manipulated in order to increase affect. For example, the therapist may move closer to the patient, may act in a more critical and less friendly way or may ask more personal questions.

Audio-video feedback

Audio or video recording of therapy sessions offers the advantage of collaboratively reviewing the tape with a view to determining NATs. The tape is paused at a point where the patient shows signs of an affect shift and the therapist can ask questions to determine the content of thought at that particular time. In effect, feedback is used as a means of prompting memories of negative automatic thoughts at particular instances in time. An advantage of this procedure is that it can distance the individual from situational affect which is useful when affect itself is overwhelming. This technique is also useful in situations where the patient is engaged in some form of social interaction task and it would be disruptive to probe for negative automatic thoughts in the situation. Audio and video recording is particularly prone to activate negative automatic thoughts concerned with public presentation and appearance, and it can therefore be used in conjunction with other exposure procedures to enhance self-consciousness and public performance anxiety.

Manipulation of safety behaviours

Since the cognitive model predicts that individuals use safety behaviours to prevent feared catastrophes, it follows that reduction or elimination of safety behaviours during exposure to fearful situations should increase the perceived likelihood of catastrophe thereby rendering negative appraisal more salient. Safety behaviours may be manipulated in two ways: they may be decreased, and they may be increased. Increasing safety behaviours in some circumstances exacerbates bodily sensations and makes misinterpretations more likely. The following extract illustrates an increased safety behaviours manipulation to elicit NATs in a panic disorder patient.

In this example, the patient’s use of safety behaviours elicited bodily sensations and associated catastrophic misinterpretations of them. In some cases, merely suggesting the abandonment of safety behaviours during exposure or role-plays will enhance fear and increase the accessibility of negative predictions associated with negative automatic thoughts. For example, an obsessional patient was recently asked not to control his thoughts next time they occurred. His immediate response was ‘I couldn’t possibly do that, I would lose control.’ Clearly this person’s NATs centred on themes of loss of behavioural and/ or mental control. Increased safety behaviours manipulations are closely associated with symptom induction techniques in that the procedure can be used to induce feared bodily sensations in some cases of panic, social phobia or hypochondriasis.

Symptom induction

We have already discussed the role of exposure to situations as a means of determining the content of dysfunctional thoughts. Another type of exposure task depends on exposure to internal bodily cues. The elicitation of bodily sensations or cognitive symptoms that are the focus of preoccupation and/ or misinterpretation can provide access to a wide range of cognitions concerning danger. For example, an obsessional patient recently was unwilling or unable to articulate his negative automatic thoughts about intrusive thoughts. His fear became accessible, however, when he was asked to deliberately form and hold in mind an unwanted intrusive image. The patient refused to comply with this request and the therapist asked about the worst consequences of performing the task. It became evident that the patient feared that he could cause harm to his family by having particular thoughts. Symptom induction techniques, both for the elicitation of NATs and for challenging them, are illustrated in the panic, social phobia, and generalised anxiety disorder chapters. Physical symptom induction through hyperventilation and exercise are common methods in the treatment of panic and health anxiety.

Ask about imagery

The occurrence of imagery is easily overlooked when eliciting negative automatic thoughts. If negative thoughts are difficult to elicit, the therapist should check for the presence of negative appraisals in the form of images. Negative automatic images may be difficult for the patient to articulate in verbal form. Whenever the content of thought is elicited or questioned, the therapist should check for the occurrence of images. Spontaneous images of catastrophe can be manipulated in session in order to activate a broader range of negative appraisals. Imagery manipulation strategies can produce affect shifts.

REATTRIBUTION METHODS

Cognitive therapy aims to modify belief at the level of negative automatic thoughts, and schemas. Durable modification of problems depends on conceptualising and changing the range of variables responsible for maintaining belief at NAT and schema levels. To this end reattribution consists of a range of interlocking strategies, the application of which is determined by the nature of individual case conceptualisations. In this section, reattribution methods are broadly divided into verbal reattribution techniques, and behavioural reattribution techniques, although this distinction is somewhat arbitrary, and both types of technique are used in unison to produce effective cognitive-behavioural change.

Verbal reattribution

Verbal reattribution techniques rely principally on discussion, and are embedded in the socratic dialogue. Twelve techniques are briefly reviewed in this section. This is by no means an exhaustive list and therapists are encouraged to devise their own reattribution methods ‘on-line’ during the course of therapy sessions.

Defining and operationalising terms

The first step in challenging negative automatic thoughts is to develop an understanding of the meaning of such appraisals to the patient. As we saw earlier, the meaning may not be immediately apparent at the surface level. Clearly, it is difficult to effectively challenge beliefs in negative automatic thoughts if their meaning is obscure. A definition of the concepts represented in negative automatic thoughts is required. For example, if a salient thought is ‘I can’t cope’ the precise meaning of the coping concept should be elicited before any challenge of that concept is initiated. Similarly, if an individual states that his / her main fear is one of ‘losing control’ it is necessary to understand the meaning of this concept for the individual. In this example, what precisely is the patient fearful of losing control of, and what would loss of control look like? The fear could conceivably involve loss of behavioural control, loss of mental control, or loss of emotional control and its appraised consequences. Once the precise nature of the fear is determined verbal and behavioural reattribution can be specifically targeted at that concept. Some useful questions for operationalising terms are:

- When you say that you (can’t cope, will lose control, can’t stand it), what do you mean?

- If you could not (e.g. cope, etc.), what is the worst that could happen?

- What would (e.g. not coping, etc.), look like?

- If that were true, what would it mean to you?

- If that were true, what would be bad about that?

- What does (e.g. coping, being in control, etc.) consist of?

- If you could (e.g. cope, have control, etc.), how would things be different from the way they are now?

Questioning the evidence

Some of the most frequently used verbal reattribution techniques are based on questioning the patient’s evidence in support of negative automatic thoughts, assumptions and beliefs. Often there is some form of supporting evidence. Rather than challenging belief in negative appraisals head-on it is useful to elicit and collaboratively explore the quality of patients’ evidence in support of negative automatic thoughts. Reinterpretation of evidence that supports NATS or the discovery by the individual that there is little supporting evidence can loosen belief in NATS. The following questions are useful for this purpose:

- What’s your evidence that (catastrophe) will happen?

- What makes you think that?

- How do you know that will happen?

- What is you reason for believing (catastrophe) will happen?

In the absence of evidence belief may be weakened. However, when evidence is given the task then becomes one of collaborative evaluation of the quality of the evidence. This can be achieved through reviewing alternative explanations for the evidence, reviewing counter-evidence, and labelling thinking errors as discussed next.

Reviewing counter-evidence

Questions for eliciting counter-evidence include:

- What is the evidence to suggest that (catastrophe) is not true or cannot happen?

- What is another way of looking at the problem?

- What is the evidence to support an alternative way of looking at it?

- Has the (catastrophe) happened yet? Why not?

A further line of questioning that may be used in this context is the ‘worst, best, most likely consequences scenario’. Here the patient is asked to describe the worst that could happen in a feared situation. This is followed by a description of the best that could happen, and is concluded by discussion of the most likely thing that could happen. This procedure is an effective means of ‘balancing out’ catastrophic thinking and should be followed up with questions aimed at eliciting evidence in support of the most likely scenario. In the following dialogue a combination of questions and techniques are used:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree