COGNITIVE TECHNIQUES

Cognitive therapy is concerned with identifying negative automatic thoughts and dysfunctional appraisals, with the aid of recall, affect shifts, role plays, imagery induction, exposure tasks, diaries, and questionnaires. Guided discovery is used to determine the meaning and nature of automatic thoughts and interpretations, and to elicit and define underlying assumptions and beliefs. Belief in dysfunctional automatic thoughts, assumptions and beliefs are modified through collaborative empiricism which involves techniques such as questioning the evidence for thoughts, examining counter-evidence, reviewing alternative explanations, education, and strategies for combating cognitive biases.

BEHAVIOURAL TECHNIQUES

Behavioural strategies are in some instances aimed at modifying symptoms directly (e.g. relaxation, distraction techniques), however, their key use is in the form of experiments to challenge belief at the automatic thought and schema levels. Some early cognitive-behavioural interventions tended to use behavioural techniques and cognitive techniques as components of eclectic treatment packages. A criticism of such approaches is that they lack theoretical integrity, and may be combining strategies in a suboptimal way. In this book a more conceptually coherent approach is advocated that uses behavioural strategies tailored specifically to modify cognition with the aim of challenging dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs. Use of a behavioural strategy, like any other strategy, should be defensible in terms of the therapeutic aims specified by an individual cognitive case conceptualisation. For example, the cognitive model of panic suggests that treatment should focus on modifying belief in symptom misinterpretations. Teaching panic patients relaxation and distraction techniques are unlikely to produce optimal changes in belief in misinterpretations since patients could attribute the nonoccurrence of catastrophe to use of their relaxation strategy. Behavioural attempts to maintain anxious sensations and reduce self-control behaviours to discover that misinterpretations are false is likely to be a better strategy. Problems of selecting behavioural strategies are diminished if the strategies are primarily selected on the basis that they will modify cognition that is central in the anxiety model being implemented. Typical behavioural strategies include, exposure experiments, mini-surveys, activity monitoring and scheduling, manipulation of safety behaviours, attentional manipulations, and symptom inductions.

In the next chapter basic techniques such as use of socratic dialogue, guided discovery, verbal reattribution and behavioural experiments are presented. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to a detailed account of the characteristics of cognitive therapy, beginning with structure and then focusing on the therapy process.

THE STRUCTURE OF THERAPY

A typical course of cognitive therapy of anxiety consists of between ten and fifteen sessions of treatment. Sessions are usually held weekly and the duration of a session is between 45 and 60 minutes. In certain cases of multiple presenting problems, such as major depression and anxiety disorders, or anxiety disorders with personality disorder, treatment may consist of a greater number of sessions. However, in some uncomplicated cases of panic disorder, social phobia, and generalised anxiety fewer than ten sessions may be required for effective treatment.

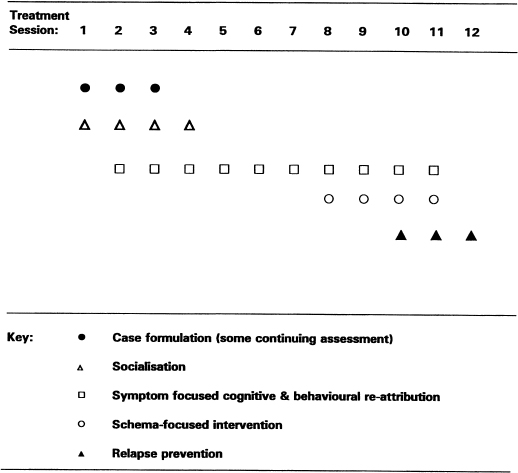

In a course of treatment, the initial sessions focus on assessment, conceptualisation, engagement, and socialisation. As treatment progresses more emphasis is placed on modifying behaviours and cognition involved in the maintenance of anxiety. Initially this is symptom-focused work, aimed at alleviating the symptoms of the presenting problem. When symptom relief is accomplished treatment focuses on underlying issues that are conceptualised as risk factors for subsequent anxiety problems or relapse. This focus is typically a component of the later stages of treatment, consisting of relapse prevention work. The termination of weekly therapy sessions is followed by scheduled ‘booster sessions’ of two or three therapy contacts within a four- to five-month period. Follow-up appointments at six and twelve months post-treatment are desirable in order to ensure that treatment gains have been maintained. A guiding structure for a twelve-week course of therapy is presented in Figure 3.0. Individual factors will of course modify timing.

Case conceptualisation (Formulation)

Following a full assessment, the early treatment sessions are predominantly devoted to conceptualisation based on a cognitive model. Conceptualisation and assessment are ongoing throughout treatment, however they occupy most of the session time during the first session of treatment. Goal setting is a component of the initial treatment session: armed with a conceptualisation and a clear set of therapeutic goals, treatment proceeds with socialisation and symptom-focused interventions. Strategies for building individual case conceptualisations are presented in each of the anxiety disorder chapters.

Figure 3.0 Typical structure of a course of treatment

Socialisation

Socialisation refers to ‘selling’ the cognitive model and providing a basic mental set for understanding the nature of treatment. Typically, this involves educating the patient about cognitive therapy, discussing the patient’s own role in treatment, and presenting the case conceptualisation.

Reading material (bibliotherapy) is provided to assist socialisation, and demonstrations of the model are used, in particular demonstrations of the links between cognition, anxiety and behaviour. Aims of socialisation include laying the foundations for a psychological explanation of presenting problems, providing a general rationale for understanding the content of treatment, and providing accurate expectations concerning the type and level of patient involvement in the treatment process.

Symptom and schema-focused intervention

The most part of cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders should consist of modifying the cognitive and behavioural variables involved in the maintenance of the presenting anxiety problem. In most cases schema-focused interventions should be introduced only after symptomatic relief is accomplished, or when there is reason to believe that underlying assumptions or beliefs are interfering with engagement in therapy or with progress.

Primary schemas in anxiety disorders are beliefs and assumptions that are hypothesised to contribute to anxiety vulnerability. These schemas tend to be modified in the latter part of treatment as a component of relapse prevention work. The same techniques that are used for modifying automatic thoughts are also used for modifying cognition at the schema level.

Relapse prevention

Relapse prevention strategies other than schema modification are undertaken in the last few sessions of treatment. Relapse prevention typically consists of checking for residual beliefs in negative automatic thoughts and challenging them. The reversal of any remaining avoidance behaviours tied to target fears is also undertaken. Information acquired during therapy is summarised and consolidated by drawing up a detailed therapy ‘blueprint’ that covers details of the model, cognitive and behavioural strategies for overcoming the problem, summaries of alternative responses, etc. Booster sessions are scheduled for monitoring progress and dealing with any emerging difficulties.

SESSION STRUCTURE

Each session of cognitive therapy has a core structure involving the following elements:

Review of objective measures

Since cognitive therapy is a problem-focused and scientific approach to treatment, measurement is a crucial component of hypothesis testing and treatment outcome assessment. Mood, anxiety, the intensity and frequency of specific symptoms, base rates for behaviour, and so on, are typical measures in treatment. (Specific measures were reviewed in more detail in Chapter 2.) Self-report questionnaires are completed on a sessional basis and diaries are provided for monitoring of thoughts and symptoms on a daily basis between therapy sessions. The initial task of the patient is to complete relevant self-report instruments just before the therapy session or during the first few minutes of therapy. The measures are reviewed collaboratively and the therapist looks for changes in anxiety, symptoms, behaviours, etc. A decrease in target measures is used to encourage the patient and signals the exploration of factors that have contributed to improvement. The factors that have been useful may be isolated for continued development. An increase in symptoms or problem status or no change signals the need to explore exacerbatory and blocking processes in treatment. Measurement is essential because it provides information that is not readily available from the patient’s general verbal account of his/her problem. Two to three minutes should be devoted to reviewing measures at the beginning of each session.

Agenda setting

Cognitive therapy is guided by a session agenda. Following the review of objective scores the agenda is collaboratively established. Initially in the course of treatment this process may have to be less collaborative as the patient knows little of what to expect from therapy. Later on, most of the responsibility for agenda setting may rest with the patient. The agenda offers a means of reinforcing a collaborative working agreement between patient and therapist. It makes both therapist and patient responsible for deciding targets in treatment, and it allows flexibility to work on problems as they emerge. The agenda should be used to maintain a focus to therapy that is consistent with the case conceptualisation and with specific goals.

The content of the agenda is influenced by the stage of treatment. However, it typically incorporates the following:

- reaction to bibliotherapy

- feedback from thought monitoring

- results of mini-experiments

- problems with homework

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree