Clinical Results of Metal on Metal Hip Resurfacing

Ryan M. Nunley

Adam Sassoon

Andrew Shinar

Gregory G. Polkowski

Introduction

Hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) has a controversial history, and through the waxing and waning of its popularity, many valuable clinical lessons have been learned leading to a refinement in its use. Initially, HRA was marketed as a better solution for young active patients. It represented a wear-resistant hard-on-hard surface, with an anatomically sized femoral head. The combination of proposed benefits, namely, improved wear over polyethylene and increased stability, lead to a surge in use. Unfortunately, increased utilization in a wide variety of patients leads to higher rates of failure, especially in women and individuals with smaller osseous anatomy. Concurrently, total hip arthroplasty (THA) employing large diameter metal-on-metal (MoM) bearing couples rose in popularity with a concomitant discovery of adverse local tissue reactions related to not only bearing surface wear, but probably more importantly corrosion at the modular head–neck junction. Increased awareness of this complication and some of its devastating manifestations leads to a grand scale-back on the usage of all MoM bearing couples and a reactionary paradigm shift back to polyethylene as the predominant bearing surface. HRA ultimately suffered and many surgeons were unwilling to learn HRA techniques or offer them to their patients secondary to these risks.

However, proponents of HRA believe that the literature and registry data suggest that a select group of patients exists, for whom HRA remains an excellent reconstructive option. This chapter presents the results of HRA so that the reader recognizes that HRA remains a valuable arrow in the quiver of an adult reconstruction specialist when proper indications are utilized.

General Outcome

The general outcome of HRA reported in the literature should be categorized and weighed based on the design of the study employed to evaluate its effectiveness as a surgical technique. Four major study designs exist and will be presented in isolation for the purposes of analysis herein: (1) series of hip resurfacings compared with historical results of conventional THA, (2) matched cohorts of resurfacing patients and THA patients, (3) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and (4) registry studies. Our analysis will examine all of these sources, noting their strengths and weaknesses, explore the effect of training, and note differences in outcome dependent on patient factors.

Case Series

The results of case series are encouraging in general as many of them focus on young active male patient populations. Daniel et al. (1) reported outstanding results with hip resurfacing in men under the age of 55 with osteoarthritis. At mean follow-up of 3.3 years, only 1 out of 440 hips had been revised and the mean Oxford score was 13.5. (The best possible Oxford score is 12, and the worst possible is 60.) Thirty-one percent of the unilateral resurfacings were involved in heavy labor, and 92% participated in leisure-time sporting activity. Survival free of revision at that time was 99.8%. Updated results show a 13-year survivorship of 98% in this young cohort (2), and recent CT scans of an entire group of resurfacings performed in 1997 show no osteolysis or pseudotumors. Certainly, in comparison to the poor results in young active patients receiving total hip replacement in years past (3,4,5), these results appear outstanding.

Cohort Studies

The success of HRA demonstrated in case series must be tempered with the understanding that substantial selection bias exists. There is certainly overlap, but hip resurfacings are performed generally in a more active, male, and younger population (6), and this population has higher expectations postoperatively (7). Cohorts of resurfacing generally have few patients with avascular necrosis and hip dysplasia (8). Matched-pair analysis with rigorous matching for age, activity level, diagnosis, and gender is necessary. The results of matched-pair analysis need also be interpreted with the understanding that a significant learning curve exists for HRA, which may impact the results when compared to THA, with which most surgeons have far more experience.

Overall, matched-pair analyses favor HRA with respect to functional results. Pollard et al. (9) showed equivalent survival, but better UCLA scores and EuroQol quality of life scores for the resurfacings at 5- to 7-year follow-up. Mont et al. (10) demonstrated superior hip kinematics in hip resurfacings compared with hip replacements, and found that the resurfacings resembled more closely patients with normal hips. Nantel et al. (11) showed improved performance of tasks during single or double leg stance for 10 resurfacing patients when compared to 10 total hip replacement patients. Zywiel et al. (12) demonstrated much greater postoperative activity levels in patients receiving resurfacing versus conventional THA in cohorts carefully matched for age, gender, body mass index, and preoperative activity levels. While postoperative hip scores, satisfaction, and pain were similar, resurfacing patients averaged activity scores of 10 and hip replacements averaged 5.

In contrast to the aforementioned series, Stulberg et al. (13) compared ceramic-on-ceramic hip replacements to resurfacings and found that the total hips performed better in the short term with regard to pain and function, but after 2 years, the two groups had similar Harris Hip Scores. It should be noted that this study included surgeons performing their first resurfacings. Results may have differed with surgeons beyond their so-called “learning curve.” Despite this fact, resurfacings did show fewer dislocations than the conventional THA.

Matched-pair analysis has also been utilized to evaluate metal ion release in HRA compared to THA. Mixed results have been seen depending on multiple variables including age, bearing surface, and head diameter. Clarke et al. (14) demonstrated higher metal ion levels in resurfacings than in a comparison group of 28 mm MoM hip replacements. This analysis, however, included many hips in the “wearing-in period,” with the measures occurring at an average of 16 months. In addition, despite being matched for activity, the resurfacing group was 7 years younger on average. Perhaps the most favorable report for HRA was a meta-analysis by Kuzyk et al. (15), which failed to show a significant difference in metal ions between MoM hip replacements and resurfacings in pooled data from 10 studies.

Randomized Controlled Trials

RCTs provide a higher level of evidence than matched-pair analysis and recently, many have emerged with short-term follow-up comparing HRA to THA. Most of these RCTs can be stratified according to THA bearing couple and head diameter, and address clinical outcome measures of function and implant survivorship; however others address very specific questions such as return to sport and bone mineral density following component placement. Our subsequent discussion of the RCTs will be categorized as such.

HRA Versus Large Diameter Metal-on-Metal THA

A study by Garbuz et al. (16), in which 73 patients were randomized to receive a large head MoM THA or a HRA, failed to show a difference in quality of life or UCLA activity scores (6.8 vs. 6.3, p = 0.2) at 1 to 2 years of follow-up. The authors found substantial differences, however, in metal ions between the groups, with the hip replacements having twofold the amount of chromium ions and 11-fold the amount of cobalt ions which suggests that metal ion release from the modular junction between the femoral head and stem body could be responsible for the much higher prevalence of adverse local tissue reactions seen with MoM bearings in THA when compared to HRA. Another study from Lavigne et al. (17) showed similar results in 48 randomized patients. Patients were studied with surveys and multiple gait and functional analyses. Again, no differences in outcome measures were noted, except that HRA patients could reach 4.6 cm further and THA patients could walk faster.

HRA Versus Small Diameter Metal-on-Metal THA

Smolders et al. looked at ion levels in an RCT, comparing 28-mm MoM THA with HRA (18). They found cobalt ions to be increased with resurfacing, but not past 6 months. Chromium ion levels were doubled with resurfacing, at early follow-up less than 24 months. Both hip resurfacings and hip replacements in this study were within acceptable ranges for metal ions, and no changes in functional outcome were observed in this study between the two groups. Vendittoli et al. (19) similarly studied cobalt and chromium ion levels and found no difference between 28-mm MoM heads and resurfacings at 2 years. Evidently, MoM THAs with small diameter MoM heads do not have the problems with metal ion elevation to nearly the magnitude of large diameter MoM heads, and thus are equivalent in this realm or perhaps slightly better than hip resurfacings. This discrepancy may be partly explained by increased metal ion generation at the trunnion when larger heads are used.

HRA Versus Metal-on-Polyethylene THA

Jensen et al. (20) compared muscle strength following HRA and metal-on-polyethylene THA and found muscle strength to be worse in resurfacings, likely due to detachment of the gluteus maximus during HRA exposure. Similarly, Peterson et al. (21) found that both HRA and THA had abnormal gait compared to the opposite side at 12 weeks, with no difference in the operated extremity between groups, except that the replacement group had better improvement of peak abductor moments.

HRA Versus THA, Mixed Articulations

Costa et al. (22) studied HRA versus a mixed group of bearings in a THA control group, using mostly ceramic-on-ceramic or MoM, although some ceramic or metal-on-polyethylene were also employed. Oxford score and Harris Hip Score were better in the resurfacing group at 12 months, but did not reach statistical significance. Complication rates between groups did not differ, but again, longer data is needed before conclusions can be drawn about survivorship.

Specific Issues: Survivorship at Longest Follow-up

The longest follow-up presently available in an RCT is 3 to 6 years. A study performed by Vendittoli found hip resurfacings to have a slight advantage, 2 and 3 points on the WOMAC

functional score at 1 and 2 years (23). Furthermore, they found no significant difference in reoperation or revision rates at 3 to 6 years.

functional score at 1 and 2 years (23). Furthermore, they found no significant difference in reoperation or revision rates at 3 to 6 years.

Specific Issues: Bone Preservation

Smolders et al. (18) reviewed bone mineral density in an RCT between HRA and THA, which demonstrated improved parameters in the HRA group. Density increased in the HRA group beyond baseline at the calcar by 1 year, whereas the THA patients showed only 82% of baseline bone density in this region. Initial statistically insignificant reductions in bone density in the femoral neck in resurfacings normalized by 1 year. It should be noted, though, that this trial compared distally fixed stems in the hip replacement group.

With respect to the acetabular side, Vendittoli et al. (24) studied the hypothesis that hip resurfacings take more bone from the acetabulum despite being bone conserving in the femur. They found, however, that the average acetabular component size did not differ significantly in their hands, 54.90 mm versus 54.74 mm for THA, and only in roughly 7% did the surgeon upsize an acetabular component to match the femoral component.

Specific Issues: Reduced Offset

Girard et al. (25) hypothesized that hip resurfacings could reduce offset in comparison to total hip replacements and via an RCT assessed whether this occurred and whether it affected function. They found a difference in offset of 7 mm between replacements and resurfacing, with the replacements gaining 4.2 mm, and the resurfacings losing 2.8 mm. Despite this difference, functional scores, limp, and Trendelenburg sign did not differ, though replacements had better jump and double walking tests. Three dislocations occurred in the replacement group, and none in the resurfacing group, despite 7 mm less offset.

Specific Issues: Leg Length

Girard et al. (26) similarly studied in a randomized fashion the effect of resurfacing on leg length, versus that of a hip replacement. THA lengthened the operative leg by a mean of 2.6 mm compared to the contralateral side, whereas HRA shortened the limb by 1.9 mm. More importantly, only 60% of the hip replacements restored limb length within 4 mm, while 86% of the resurfacings did so. The authors showed more precision in restoring proximal femoral anatomy with resurfacing over hip replacement, and felt that the enhanced stability to its large head allowed them to avoid overlengthening to ensure stability. The caveat regarding this issue; however, is that HRA is ineffective in restoring leg length in patients with a pre-existing discrepancy.

Specific Issues: Return to Sport

The ability to return to sport following HRA versus THA was investigated by Lavigne et al. (27) in an RCT. While HRA patients greatly outperformed THA in total activity score, 17.9 to 12.4 (p = 0.001), the patients did not differ significantly in UCLA scores, WOMAC scores, or VAS score on satisfaction with return to sporting function. The authors felt the results to be less pronounced than expected, and suggested that the larger femoral head sizes used in resurfacings may have produced fewer episodes of instability, facilitating return to a higher level of activity. The authors later replicated this study with large metal heads, and did not find significantly different results between the groups (17).

Registry Data

Registry data is a powerful tool that allows for the analysis of a massive volume of patients with respect to implant survivorship. Its potency wanes with respect to other clinical outcomes such as pain, return to activity, or patient satisfaction. Furthermore, it is incapable of detecting patients for whom revision surgery is indicated that are unwilling, or have yet to undergo revision surgery.

In addition, registry data has several other limitations even when used in the analysis of implant survivorship. Registries incorporate all implant manufacturers and models, including those with an increased rate of failure or those, which have subsequently been removed from the market (Graves, 2011). Thus conclusions drawn from this data should be weighed appropriately. For instance, the Durom, ASR, Bionik, Cormet 2000 HAP, and Recap have been identified as HRA devices with an increased risk of failure. Though not used now in significant numbers, these components did account for 21.7% of the hip resurfacings performed as recently as 2007. Survivorship data tabulated from prior to this time would reflect the performance of these suboptimal designs. Moving forward one would expect an improvement with their discontinued use.

Other factors that weigh into registry data include patient selection and demographics with respect to age and gender. These factors are of critical importance when analyzing survivorship of HRA versus THA. Taking all hip replacements and resurfacings into account, the Australian Registry shows revision rates of 4.4% and 6.2% at 7 and 10 years for THA (Table 70.1), and 6% and 7.5% at 7 and 10 years for

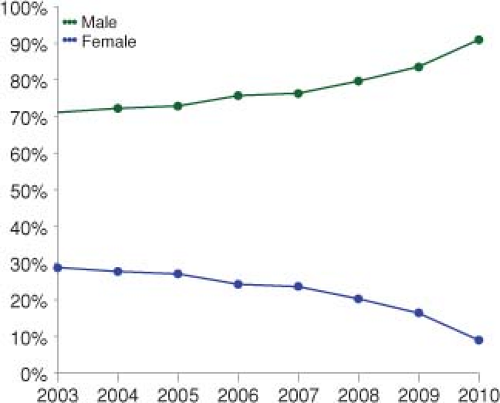

HRA (Table 70.2). Indications for resurfacing have changed during this time period, with the procedure being less commonly performed in older or female patients (Figs. 70.1 and 70.2). Less than 10% of resurfacing patients are now female or older than 65 in Australia. Future results will likely reflect this positive change when all patients are considered.

HRA (Table 70.2). Indications for resurfacing have changed during this time period, with the procedure being less commonly performed in older or female patients (Figs. 70.1 and 70.2). Less than 10% of resurfacing patients are now female or older than 65 in Australia. Future results will likely reflect this positive change when all patients are considered.

Table 70.1 Yearly Cumulative Percent Revision of Primary Total Conventional Hip Replacement (Primary Diagnosis OA) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Table 70.2 Yearly Cumulative Percent Revision of Primary Total Resurfacing Hip Replacement (Primary Diagnosis OA) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

When considering only males, the Australian Registry shows similar failure rates at 7 years for THA and HRA in the less than 55 and 55 to 65 age groups. For the former, the failure rate is 4.6% for THA and 4.2% for HRA; for the latter the failure rate is 4.9% for THA, compared to 4.3% for HRA. At the 10-year time point; however, hip replacements in males show an inflection toward an increased revision rate, with THAs failing at a rate of 7.5% (6.1 to 9.2) and 8.0% (6.9 to 9.3) in men less than 55 and men 55 to 65, respectively. Greater number of hip resurfacings with 10-year follow-up will be required to perform an adequate or meaningful comparison.

Other registries with shorter follow-up than the Australian Registry show similar findings with regard to gender influences on results of HRA, but differ with respect to improved survivorship of HRA over THA. The Finnish registry shows no difference in survival between 4,401 hip resurfacings and 48,409 total hip replacements at mean 3.5- and 3.9-year follow-up, respectively (28). Female patients had double the risk of failure of male patients (p < 0.001), as in Australia. Survivorship of HRA and THA were equal in males at these time points, with the majority of THAs being cemented. HRAs performed in males younger than 55 showed improved survivorship when compared to those performed in males older than 55.

Figure 70.1. Primary total resurfacing hip replacement by gender. (Reprinted with permission from the Australian Orthopaedic Association Annual Report 2011. Available at https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/en/annual-reports-2011.) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree