Chronic, Locked Anterior, and Posterior Dislocations

Christian Gerber

C. Gerber: Professor and Chairman, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

LOCKED POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

Diagnosis

Chronic, locked posterior dislocation is of diagnostic interest because almost two-thirds of the posterior dislocations are not recognized initially.3,4,8,14,19 In my experience, 12 of 21 patients with dislocation persisting for more than 4 weeks were referred for treatment without the correct diagnosis.

Posterior dislocations are associated with fractures of the surgical neck of the humerus in almost 50% of the cases. In acute cases, these concomitant fractures, which usually also involve one of the tuberosities,8 must be identified, because they may be displaced during reduction of the dislocation. Displacement of a fracture-dislocation is almost invariably followed by avascular necrosis and subsequent collapse of the humeral head. In chronic cases, the mild to moderate malunion at the surgical neck level may significantly complicate prosthetic reconstruction of the proximal humerus.

In the typical history of the patient with a traumatic posterior dislocation, the shoulder has undergone a violent injury, most commonly during a motor vehicle accident3 or during a seizure. Posterior dislocations that have occurred during convulsions often have a somewhat unclear history, because the patient is completely unaware of the injury and only notices that, for no apparent reason, he or she can no longer externally rotate the arm.

The cause of locked posterior dislocation is a major trauma; there is no particular predisposition to this injury. During convulsions, which precipitate about one-third of all posterior dislocations, the shoulder is more likely to be dislocated posteriorly, because the internal rotators are much stronger than the external rotators. However, anterior dislocations can also be caused by epileptic seizures.

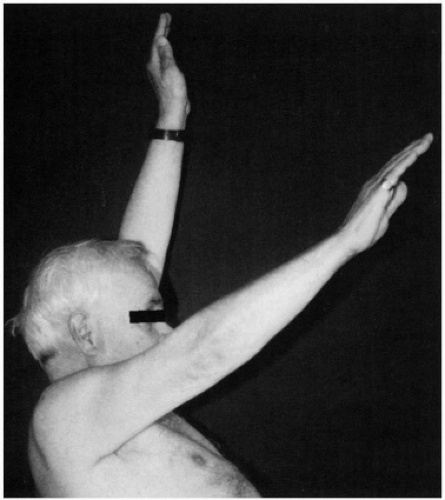

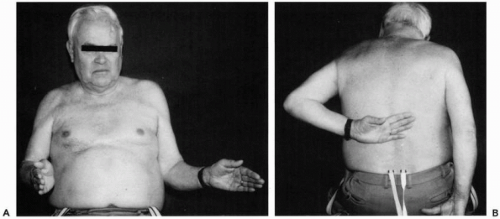

On clinical examination, the coracoid process is prominent, and the proximal humeral shaft is oriented somewhat posteriorly. Active anterior elevation is limited but generally remains around 100 degrees (Fig. 5-1). Active and passive external rotation are always absent (Fig. 5-2). The arm is locked in internal rotation of 10 degrees to 60 degrees.

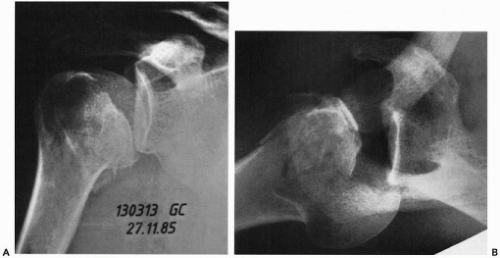

The anteroposterior and axillary lateral x-ray views always provide diagnostic information (Fig. 5-3). It may be difficult to make the diagnosis solely on the basis of an anteroposterior radiograph, especially if it is not taken with the central x-ray beam parallel to the glenoid fossa. The axillary lateral view is optimal, enabling the examiner to make the diagnosis and estimate the size of the lesion of the humeral head. For a more refined diagnostic workup that includes preoperative planning, computed tomography (CT) is the optimal imaging method. Because the lesions are mostly skeletal, CT provides a more accurate study than that provided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Lesions

Several lesions can be created by a locked posterior dislocation. Almost one of two cases is associated with a fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus (see Fig. 5-3), which may pose an additional challenge for treatment. Fractures of the posterior glenoid rim are rare, but chronic destruction caused by active or passive repetitive rotational movements may necessitate surgical treatment.3 Posterior capsular lesions are probably always present.3,17,18 Scougall20 demonstrated in monkeys that these lesions heal spontaneously, and my experience suggests that this pattern also occurs in humans. Ruptures of the rotator cuff have been found frequently in experimental posterior dislocations.17,18 My colleagues and I have observed three cases with concomitant rupture of the rotator cuff, which invariably involved the supraspinatus tendon. However, we did not find that lesions of the posterior cuff were constant features. The anteromedial humeral head defect14 is a constant feature, and it is the key abnormality of locked posterior shoulder dislocation. In the absence of concomitant lesions, reconstruction of the humeral head defect by the restoration of the humeral head surface6 or by filling the anteromedial humeral head lesion8,14,15 can restore stability and function of the shoulder without other surgical corrections.

Figure 5-2 Same patient as in Figure 5-1. (A) He has a severe loss of external rotation that is partly compensated by thoraco-scapular motion. (B) The loss of internal rotation documents that rotational movements in the glenohumeral joint are virtually absent. At this 5-year follow-up visit, these active movements were free of pain, and the patient was satisfied with his shoulder function. |

Treatment

Skillful Neglect

Before any treatment is undertaken, it is necessary to establish whether treatment is necessary or whether the natural history may be as favorable as surgical treatment. All patients with posterior dislocations have lost glenohumeral rotation and are therefore definitely limited, but they regain functional anterior elevation. The natural history of locked posterior dislocation is quite favorable. My colleagues and I have observed four untreated patients over

several years (see Figs. 5-1, 5-2 and 5-3). All of them remained free from pain or had minimal pain, and each had a functional shoulder value of between 60% and 85% of normal, as judged by using the Constant score.1,2 This is comparable to the function obtained with good shoulder fusion. Twenty shoulders that underwent arthrodesis were reviewed (L. Nagy and C. Gerber, unpublished data), and the overall outcome for these cases was not better than the outcome for untreated, locked posterior dislocations.

several years (see Figs. 5-1, 5-2 and 5-3). All of them remained free from pain or had minimal pain, and each had a functional shoulder value of between 60% and 85% of normal, as judged by using the Constant score.1,2 This is comparable to the function obtained with good shoulder fusion. Twenty shoulders that underwent arthrodesis were reviewed (L. Nagy and C. Gerber, unpublished data), and the overall outcome for these cases was not better than the outcome for untreated, locked posterior dislocations.

On the basis of these observations and the results of treatment of this condition, I think that skillful neglect must be considered, if the patient is old, has limited demands for the affected shoulder, is able to reach the mouth and possibly the front, and has a normal contralateral shoulder. The same conservative approach is warranted if the patient has medical or other concomitant problems suggesting that he or she may be unable to comply with a rehabilitation program. After epileptic seizures, surgery is only considered if the seizures are adequately controlled by medical treatment.

Closed Reduction for Small Defects

If the anteromedial humeral head impression fractures are very small (less than 25% of the cartilage surface), and there is no recent subcapital fracture, a reduction with the patient under general anesthesia may be attempted. If closed reduction is possible, the stability is then tested. If redislocation does not occur with internal rotation by taking the affected hand to the abdomen, the arm is mobilized in a splint in neutral rotation for 4 weeks, and rehabilitation is then instituted. The arm must not be brought behind the trunk for a minimum of 6 weeks. If closed reduction is possible, a good outcome can be expected without additional surgery. If an open reduction is necessary, it appears logical to ascertain whether the stability is restored. Although transferring the lesser tuberosity with its attached subscapularis tendon into the articular defect is the standard,16 my colleagues and I prefer to reconstruct the humeral head using autogenous or, more frequently, allograft bone,6 as used in defects involving 25% to 50% of the articular surface.

Reconstruction of Defects up to Half of the Articular Surface

Indications

The size of the anteromedial humeral head defect dictates the treatment of locked posterior dislocations. McLaughlin14 first recognized the significance of this lesion and recommended transfer of the subscapularis tendon into the defect to prevent recurrence of glenohumeral instability. Dubousset3 later recommended reestablishing the contour of the humeral head with autogenous bone graft in conjunction with reconstructing the posterior glenohumeral

capsule. Many modern surgeons recommend transfering the lesser tuberosity with its attached subscapularis tendon into the humeral head defect, if it comprises up to 40% of the humeral head, and, for defects of more than 40% of the articular surface, total shoulder or hemiarthroplasty is recommended.

capsule. Many modern surgeons recommend transfering the lesser tuberosity with its attached subscapularis tendon into the humeral head defect, if it comprises up to 40% of the humeral head, and, for defects of more than 40% of the articular surface, total shoulder or hemiarthroplasty is recommended.

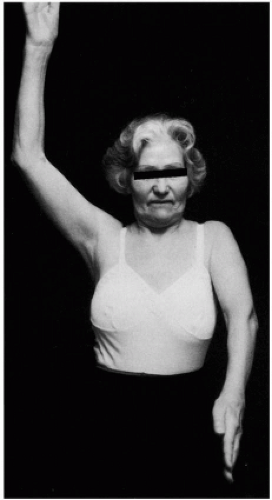

Figure 5-4 Locked posterior dislocation secondary to an epileptic seizure in a 68-year-old woman. Active anterior elevation is only 25 degrees. |

Chronic posterior dislocations with large anteromedial humeral head defects are, fortunately, rare. Neer and Hughes16 modified McLaughlin’s subscapularis transfer14 and transferred the lesser tuberosity with its attached subscapularis tendon into the defect. The treatment of lesions involving 25% to 50% of the articular surface with transfer of the lesser tuberosity has repeatedly been reported to yield satisfactory results.8,16 Hawkins et al.8 reported good results in nine cases of the subscapularis transfers. Walch et al.21 reported three excellent, one good, five fair, and one poor outcome after subscapularis transfer in ten patients with anterior head defects of less than 50%. For defects that are larger than 50%, these surgeons attempted rotational osteotomy and reported unsatisfactory results.

My colleagues and I have reported the results of reconstructing the shape of the humeral head by elevating the depressed cartilage and subchondral buttressing with autologous cancellous bone graft as a joint-preserving alternative to hemiarthroplasty in the acute setting.5 Subsequently, we reported the results obtained with humeral head reconstruction, using allogenic bone in the chronic setting.6 We have come to prefer reconstructing the shape of the humeral head, because it seems more logical than other approaches, or prosthetic replacement if humeral head reconstruction is not possible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree