Chordoma

Chordoma is a neoplasm that develops from remnants of the primitive notochord. It apparently can arise from the normal products of the notochord (the nuclei pulposi) or from abnormal rests of notochordal tissue. Ordinarily, it grows slowly and is malignant because of local invasion, but metastasis is relatively uncommon.

Chordoma has a distinct predilection for the ends of the spinal column. Thus, most of the lesions are found in the sacrococcygeal region and at the base of the skull near the site of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis. Small, nonneoplastic masses of vestigial notochordal tissue are occasionally found near the spheno-occipital junction in the midline and have been termed ecchondrosis physaliphora.

This tumor is relatively uncommon in the spinal column, especially in the dorsal portion, which is curious because the largest masses of notochordal products, in the form of nuclei pulposi, occur in this region.

One might question whether a chordoma is correctly classed among the neoplasms of bone. However, the intimate relationship of the notochord with the skeleton and the clinical and radiographic features of these tumors make the inclusion logical.

INCIDENCE

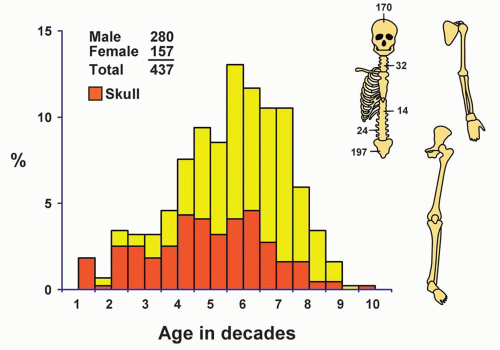

Chordoma is a relatively rare neoplasm and accounted for 6.15% of the malignant tumors in the Mayo Clinic files (Fig. 21.1).

SEX

Chordoma affects males much more commonly than females. In the overall group of 437 patients, approximately 64% were males. However of the 170 patients with involvement of the spheno-occipital region, only just over 55% were males. The male predominance was most pronounced in the 197 patients with tumors of the sacrum; approximately 71% were males.

AGE

Chordoma is distinctly uncommon in patients younger than 30 years. Only eight patients were in the first decade of life, and all the tumors involved the spheno-occipital region. Eighteen patients were in the second decade, and twelve had tumors involving the clivus. Four patients had involvement of the spine and two, the sacrum. The youngest patient with a lesion of the sacrum was a 13-year-old girl. Chordomas in the spheno-occipital region are recognized clinically about a decade earlier in life than those in the sacrococcygeal region. In the Mayo Clinic series, there are no examples of high-grade chordomas of childhood, as described by Coffin and coauthors.

LOCALIZATION

Chordoma is so strictly localized to the midline regions of the body that this affords important diagnostic evidence. Just over 45% of the lesions occurred in the sacrococcygeal region, and just over 38% involved the spheno-occipital region. Of the 70 lesions involving the rest of the spine, 32 involved the cervical spine, 24 the lumbar spine, and only 14 the thoracic spine. The tumor frequently involved more than one contiguous vertebral body.

SYMPTOMS

The duration of symptoms before the patient seeks medical care varies from months to several years. Pain is a nearly constant feature of sacrococcygeal chordoma, and it characteristically occurs at the tip of the spinal column. Constipation due to the presence of the tumor and complaints resulting from pressure on or destruction of nerves emerging from the distal portion of the spinal cord may develop. Nearly all these tumors extend

anterior to the sacrum, but in rare instances, a sacrococcygeal chordoma produces a postsacral mass.

anterior to the sacrum, but in rare instances, a sacrococcygeal chordoma produces a postsacral mass.

Figure 21.1. Distribution of chordomas according to age and sex of the patient and site of the lesion. |

Spheno-occipital chordoma may cause symptoms referable to any of the cranial nerves, but symptoms resulting from involvement of the nerves to the eye are by far the most common. This tumor may destroy the pituitary gland and produce evidence of its dysfunction, it may protrude laterally and give signs suggestive of a tumor in the cerebellopontine angle, or it may erode inferiorly and obstruct the nasal passages. A large intracranial extension may evoke the general features of intracranial neoplasms.

Chordomas arising along the rest of the spinal column frequently produce either symptoms, by compression of the spinal nerve roots or the spinal cord, or a mass.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Almost every sacrococcygeal chordoma has a presacral extension that may be detected on careful rectal examination. The mass is firm and fixed to the sacrum. Digital and proctoscopic examinations disclose that the lesion is extrarectal. Evidence of nerve dysfunction, such as “cord” bladder, anesthesias, and paresthesias, is relatively unusual and late to appear.

Chordomas that arise at the base of the brain may, as indicated, produce signs referable to any of the cranial nerves or to involvement of the pituitary gland. Examination of the visual fields may disclose defects that are suggestive of the correct diagnosis. Some may present as a cerebellopontine angle tumor. Only rarely does the patient complain of nasal obstruction.

Because chordoma of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar portions of the vertebral column may present posteriorly, laterally, or anteriorly, a great variety of symptoms are produced. For example, a chordoma in the cervical region of the spinal column may produce clinical features suggestive of chronic retropharyngeal abscess. Physical examination often provides evidence of encroachment on the nerves or spinal cord.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

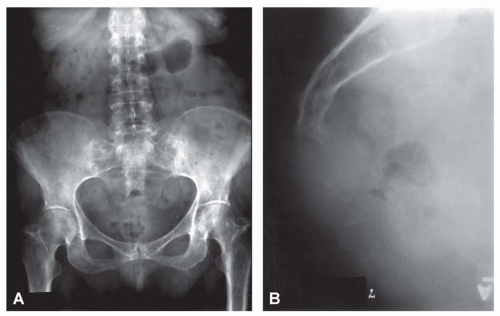

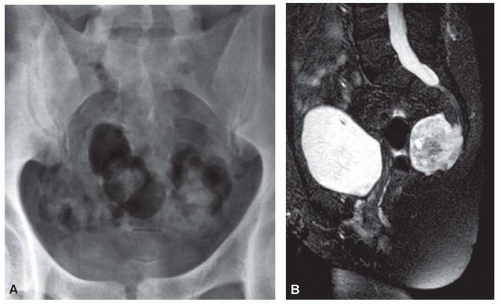

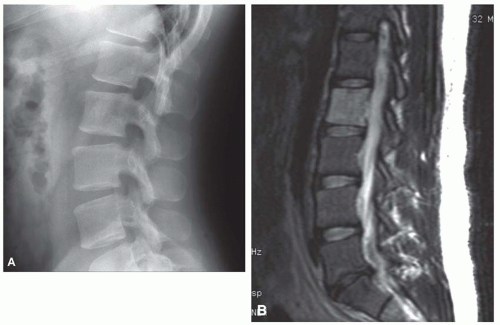

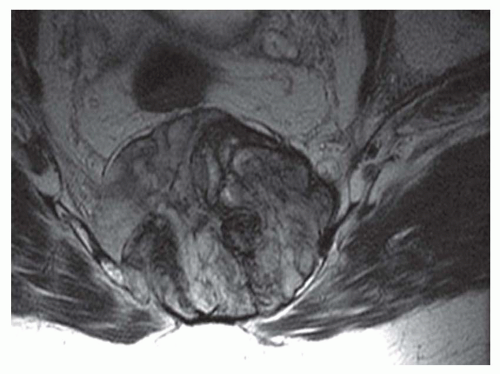

Radiographic features depend on the site of involvement. In a study of 20 cases of chordoma involving the sacrococcygeal region, Utne and Pugh found evidence of the pathologic process in 85% of cases. Plain radiographs showed involvement of the bone in 75% of cases and a soft tissue mass in 85% (Fig. 21.2). Typically, the area of destruction begins in the midline and shows irregular areas of destruction. A soft-tissue mass is usually present anteriorly. Indirect evidence of displacement of the rectum may be seen. Increased densities are seen in half of the cases. These densities may represent calcification within the neoplasm or residual bony trabeculae. Because of the overlying bowel gas shadows, chordomas of the sacrum are frequently overlooked on anteroposterior radiographs, delaying diagnosis. A lateral view is more likely to show the lesion. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have been helpful in recognizing the lesion and defining its extent for planning surgery (Figs. 21.3, 21.4 and 21.5).

Figure 21.5. Chordoma forming a massive sacral tumor. Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful in delineating the extent of the tumor. |

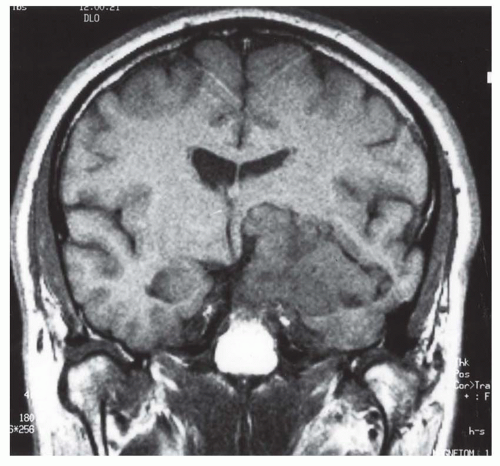

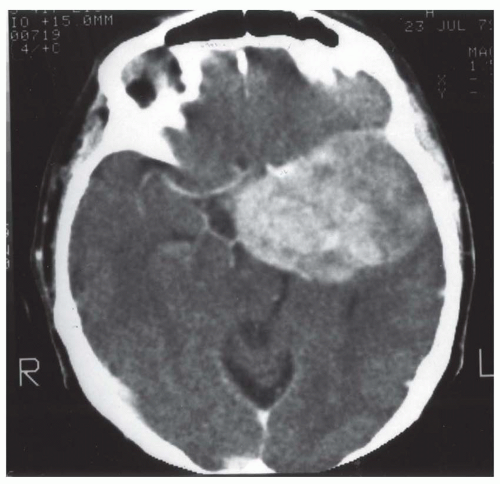

Cranial chordoma nearly always produces changes visible on plain radiographs. Destruction of bone in the spheno-occipital and hypophyseal regions is usually evident. Some portion of the sella tursica is affected in the majority of cases. Destruction of the clivus is commonly seen. Computed tomograms show the presence of calcific densities in almost three-fourths of the cases of cranial chordomas. Magnetic resonance imaging is now considered the best single test, especially because of its ability to define the extent of the tumor (Figs. 21.6 & 21.7).

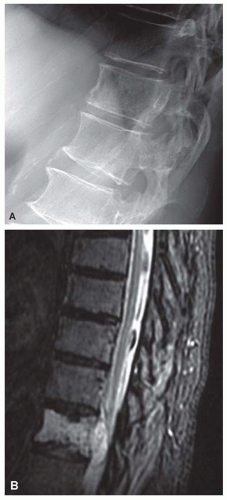

Chordomas that involve the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar segments of the spinal column usually produce marked radiographic changes (Fig. 21.8). Zones of bone destruction, sometimes containing sclerotic foci, are seen to involve one or more vertebrae (Fig. 21.9). In a study of 14 cases of chordomas of the spine, de Bruine and Kroon found that 64% were sclerotic and the rest were purely lytic. Some of the tumors, especially if they displace the pharynx or trachea, produce a pronounced soft-tissue mass.

Figure 21.6. Computed tomogram of a large chordoma of the clivus. The lesion arises in the midline and extends to the left. |

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

A chordoma is a soft, lobulated, grayish tumor that is semitranslucent and resembles a chondrosarcoma or even a mucinous adenocarcinoma. It is usually well encapsulated, except in the region of bone invasion, where a distinct edge of the tumor may not be delineated. Sacral chordomas nearly always have a presacral extension that is usually covered by the elevated periosteum. The lesion may extend into the spinal canal. Spheno-occipital chordomas almost always bulge into the cranial cavity and distort the structures at the base of the brain. Sometimes, a chordoma at the base of the brain penetrates and fills the sphenoid sinus or even the nasal or nasopharyngeal cavities. In three tumors, all involving the spine, radiographic and surgical features suggested no involvement of bone. These appear to be soft-tissue lesions. In all other respects, however, they appear to be typical chordomas (Figs. 21.10, 21.11, 21.12, 21.13, 21.14 and 21.15).

An occasional chordoma contains focal calcification or ossification, but such foci are rarely prominent. Like chondrosarcomas, some chordomas are relatively firm and other are extremely myxoid and semiliquid.

Recurrences often produce multiple nodules in the region of the previous surgical excision. Metastasis is usually through the hematogenous route. The process may develop in an unusual location, including the skin. Su and coauthors reported involvement of the skin in 19 of 207 chordomas studied. Seven of these were recognized at the time of clinical presentation. Most of this involvement was at the site of the neoplasm. They found only one metastatic focus in a distant site.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree