Chondroma

Chondroma is a benign tumor composed of mature hyaline cartilage. Most commonly, chondromas are centrally located in bone, and such tumors are called enchondromas. Less often, they are distinctly eccentric and cause the overlying periosteum to bulge. This type has been called periosteal chondroma. In thin or flat bones, such as the ribs, scapula, or innominate bone, the exact origin of the chondroma, that is, whether central or subperiosteal, often cannot be determined because the landmarks are destroyed by the tumor. Sometimes a tumefactive but nonneoplastic proliferation of costal cartilage simulates a chondroma. Such proliferation can even be mistaken for chondrosarcoma; typically, the radiograph shows no abnormality.

Multiple chondromas represent a dysplasia of bone characterized by failure of normal enchondral ossification and proliferation of tumefactive cartilaginous masses in the metaphyseal and adjacent regions of the shaft. A few or many bones may be affected. With widespread involvement and a tendency to unilaterality, this condition is often called Ollier disease. In addition to tumefaction, this disease results in concomitant bowing and shortening of bones. In fact, multiple chondromas and fibrous dysplasia both result from a disorder of ossification, and this relationship is evident in the lesions that contain histopathologic features of both. Multiple chondromas should be differentiated from skeletal osteochondromatosis (multiple osteochondromas). When associated with angiomas of the soft tissues, skeletal chondromatosis is referred to as Maffucci syndrome. Other rare syndromes associated with the skeletal chondromas have been recognized. Although completely reliable figures are not available, it has been estimated that chondrosarcoma develops by age 40 in approximately 25% of patients with Ollier disease. The incidence of malignancy in Maffucci syndrome is considered to be higher, although in a large review of reported cases, Lewis and coauthors estimated that the incidence of neoplasia in Maffucci syndrome was 23%.

Not included in the Mayo Clinic series are cartilaginous tumors arising in unusual sites, such as the larynx and the synovial membranes. These tumors have unusual characteristics, the most significant of which is a less aggressive clinical behavior than their histologic appearance suggests. The same attribute applies to the not uncommon extraosseous cartilaginous tumors of the hands and feet, most of which are small and many of which are probably derived from the synovium. Frankly malignant extraosseous neoplasms that are definitely cartilaginous are rare. Rarely chondromas, occasionally large, occur in the dura mater, often in the falx cerebri.

INCIDENCE

In the Mayo Clinic series, chondromas constituted 15.6% of benign tumors and 4.7% of all tumors. These figures, however, do not reflect the true incidence of chondromas because they are generally asymptomatic.

SEX

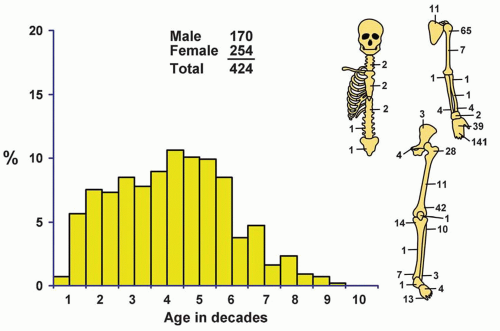

In the overall group of chondromas, there was a distinct female predominance, whereas for patients with multiple chondromas, the reverse was true.

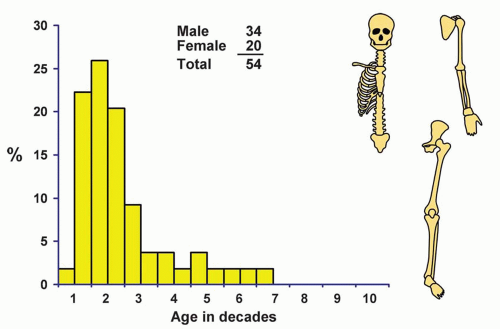

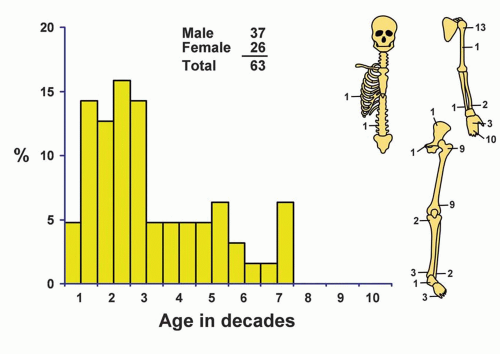

AGE

Patients were fairly evenly distributed throughout all decades of life; approximately 50% were in the second, third, and fourth decades. Patients with multiple lesions required surgery, on average, at a younger age; approximately 71% were in the first and second decades of life.

LOCALIZATION

More than 41% of the tumors were in the small bones of the hands and feet, chiefly in the phalanges, and 91% of these were in the hands. Chondroma is by far the

most common tumor of the small bones of the hands. Four of the lesions of the innominate bone involved the pubis and three the ilium. Chondroma does not usually occur in the bones most commonly affected by chondrosarcoma. There were only two chondromas of the sternum. Almost all chondroid neoplasms of the sternum are malignant. Two intracranial chondromas of meningeal origin were excluded. There were no benign cartilaginous tumors of the base of the skull in the Mayo Clinic series, and some of these rare lesions reported were probably chordomas or related to them (Figs. 3.1 & 3.2).

most common tumor of the small bones of the hands. Four of the lesions of the innominate bone involved the pubis and three the ilium. Chondroma does not usually occur in the bones most commonly affected by chondrosarcoma. There were only two chondromas of the sternum. Almost all chondroid neoplasms of the sternum are malignant. Two intracranial chondromas of meningeal origin were excluded. There were no benign cartilaginous tumors of the base of the skull in the Mayo Clinic series, and some of these rare lesions reported were probably chordomas or related to them (Figs. 3.1 & 3.2).

Figure 3.1. Distribution of chondromas according to age and sex of the patient and site of the lesion. |

Eighteen of the periosteal chondromas involved the femur, and 14 involved the humerus. The proximal metaphysis of the humerus was the most common location for periosteal chondroma (Fig. 3.3).

Only one chondroma in the Mayo Clinic series was definitely epiphyseal in location.

SYMPTOMS

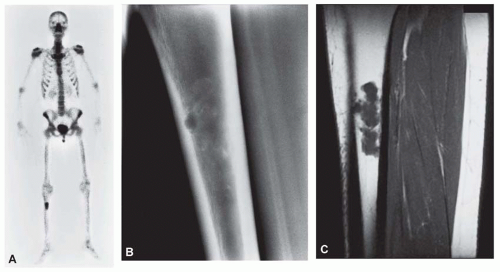

Chondromas of the long tubular and flat bones are generally asymptomatic. Chondromas are frequently

“hot” on isotope bone scans and are discovered in patients undergoing the scan usually for evidence of metastatic carcinoma. If the radiographic features suggest an enchondroma, biopsy is not necessary. Three chondromas were incidental findings with other neoplasms: one myeloma, one metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, and one adamantinoma. One patient with enchondroma of the femur had osteomalacia, but the latter was caused by a typical phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the first cervical vertebra. Chondromas of the small bones tend to become painful because they frequently undergo pathologic fracture. It is unusual to see a pathologic fracture in a chondroma of larger bones.

“hot” on isotope bone scans and are discovered in patients undergoing the scan usually for evidence of metastatic carcinoma. If the radiographic features suggest an enchondroma, biopsy is not necessary. Three chondromas were incidental findings with other neoplasms: one myeloma, one metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, and one adamantinoma. One patient with enchondroma of the femur had osteomalacia, but the latter was caused by a typical phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the first cervical vertebra. Chondromas of the small bones tend to become painful because they frequently undergo pathologic fracture. It is unusual to see a pathologic fracture in a chondroma of larger bones.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Chondromas produce a localized, central region of rarefaction. Any portion of the bone may be involved, but in the long bones, the tumors tend to be metaphyseal. In the short tubular bones, chondromas tend to involve the middle portion. The amount of calcification varies from slight to marked. Long-bone chondromas are generally mineralized, whereas small-bone chondromas tend to be less so. The pattern of mineralization is described as popcornlike or ringlike. The mineralization is usually distributed uniformly throughout the lesion. Uneven mineralization should arouse suspicion of chondrosarcoma. The bony cortex overlying a long-bone chondroma is uninvolved. Scalloping of the endosteal aspect of the cortex is evidence of growth but not necessarily of malignancy (Figs. 3.4, 3.5 and 3.6).

Magnetic resonance images and computed tomograms do not add significantly to the diagnostic features in enchondromas. However, computed tomograms may show calcification not appreciated on plain radiographs. On magnetic resonance images, enchondromas tend to be dark on T1-weighted images and bright on T2-weighted images and have a characteristic lobulated appearance. Magnetic resonance images and computed tomograms may also be helpful in confirming the lack of permeation and cortical involvement (Figs. 3.7 & 3.8).

The cortex is thinned in small-bone enchondromas. Such involvement of the cortex should not be considered a sign of malignancy in small bones. Chondrosarcoma, which is extremely unusual in this location, permeates through the cortex into the soft tissues.

Periosteal chondromas tend to be small, usually 2 to 3 cm in greatest dimension. The lesion is situated on the surface of bone, with scalloping of the underlying cortex. Usually, there is a rim of sclerosis in the underlying bone, and the lesion is sharply marginated. The cortex tends to overhang the lesion, giving rise to a buttress effect (Figs. 3.9 & 3.10).

In several conditions, multiple chondroid lesions may be seen in the skeleton. Some almost surely represent true chondroid neoplasms and, hence, may be called multiple chondromas. Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome probably are dysplastic conditions, so the term chondrodysplasia may be used. However, the distinction between multiple chondromas and chondrodysplasias may not always be possible. In Maffucci syndrome and Ollier disease, the number of bones involved is variable. In some patients, the skeleton is involved extensively, whereas in others, only one-half of the body, or even one limb, is affected. It is possible that there are examples of Ollier disease that involve a single bone.

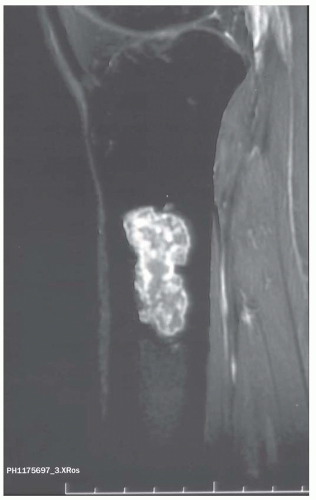

Figure 3.7. T1-weighted MRI of enchondroma of the distal femur in a 50-year-old man. The lobulated appearance is typical (Case provided by Dr. David Aldrich, Lafayette, Indiana.). |

Figure 3.8. T2-weighted MRI of enchondroma of the proximal tibia in a 42-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer. The signal is bright, and the typical lobulation is apparent. |

In chondrodysplasias, the radiographs show massive calcified chondroid lesions involving the metadiaphyseal regions of long bones. Flat bones also may be affected. The bones involved tend to be expanded, and the calcification may be popcornlike, as in chondroma, or, more characteristically, have a linear pattern. In addition to expansile masses within the marrow, lesions may also occur on the surface of bone. This appearance may give rise to a false impression of a destructive tumor. In Maffucci syndrome, soft tissue hemangiomas are present in addition to the bony lesion and may be visualized on plain radiographs because of the presence of phleboliths. Serial radiographs in affected patients have shown “healing” of the lesions. The bones appear expanded and deformed, but the characteristic calcification is usually absent and, hence, the features may not be diagnostic in adult patients (Fig. 3.11).

Bone infarcts may resemble calcifying cartilaginous neoplasms, but infarcts typically are lucent centrally and well separated from surrounding normal bone by a zone

of calcification or even ossification at their periphery. Enchondromas generally have mineralization in the central regions.

of calcification or even ossification at their periphery. Enchondromas generally have mineralization in the central regions.

Figure 3.10. The proximal humerus is also commonly involved with periosteal chondroma. The radiographic appearance is that of a surface lesion with marginal buttresses. |

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

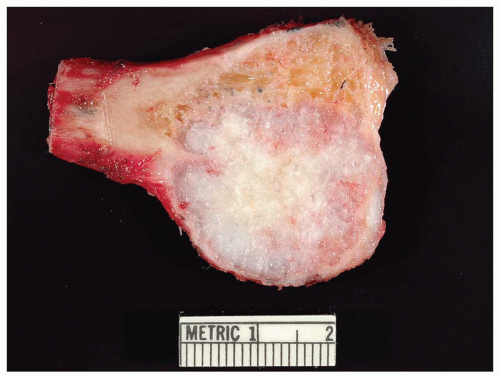

Chondroma is characteristically composed of confluent masses of bluish, semitranslucent hyaline cartilage with a distinctly lobular arrangement. The lobules may vary from a few millimeters to a centimeter or more in diameter. The periphery of the lesion may be somewhat indistinct because ramifications of the cartilaginous tumor sometimes penetrate into adjacent marrow spaces. Tumors characterized by radiographic evidence of punctate areas of calcification have calcified masses scattered throughout, and occasionally these lesions are heavily calcified and ossified. Although the gross characteristics of the solitary tumor are similar to those of multiple tumors, the latter tend to have well-circumscribed nodules separated by apparently normal marrow. This appearance, which may give rise to a false impression of permeation, represents multifocality (Fig. 3.12).

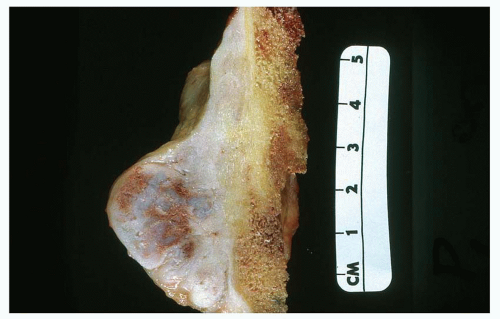

Periosteal chondromas produce a well-marginated defect in the underlying cortex and a bulge in the contour of the bone. They lie in a concavity in the bone, and their internal aspect is marked by a thin sclerotic zone. The outer surfaces are smooth and appear to be demarcated by a fibrous capsule. Periosteal chondromas tend to be small and rarely exceed 5 cm in greatest dimension (Fig. 3.13).

Figure 3.12. Enchondroma of the proximal fibula. There is extensive cortical erosion, but the fibula is considered a small bone and the cortical erosion does not connote malignancy. |

Figure 3.13. Periosteal chondroma in the distal femur. The lesion, involving the cortex and extending into soft tissue, is small and well circumscribed. The medullary cavity is not involved. |

Chondroma is characteristically a small tumor, and when a tumor of hyaline cartilage that is several centimeters in greatest dimension is seen, the lesion should be examined carefully for evidence of malignancy. Erosion or thickening of the overlying cortex is an ominous sign, often evident on radiographs. Myxoid change in the matrix, especially if it gives rise to cystification, also is an ominous sign. The rules are different in the small bones because, as indicated above, the cortex may be paper thin. Moderate myxoid change in the matrix can also be seen in chondromas of the small bones and periosteal chondromas.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

The histologic features of chondromas vary considerably, depending on the location of the lesion. Hence, it is important to have information about location, radiographic features, and clinical features before a definite diagnosis is made. It is reasonable to discuss the features separately (Figs. 3.14, 3.15, 3.16, 3.17, 3.18, 3.19, 3.20, 3.21, 3.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree