Cervical Osteotomies for Kyphosis

Michael P. Kelly

Adam L. Wollowick

K. Daniel Riew

DEFINITION

The precise definition of cervical kyphosis is not clearly described. Normal alignment from C2 to C7 in the sagittal plane is approximately 20 degrees of lordosis.

ANATOMY

With normal alignment, the load bearing axis of the cervical spine lies in the posterior third of the vertebral bodies.

The foramen transversarium of C7 generally contains only veins; however, vertebral artery anomalies do exist and careful examination of the preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is necessary.4

As the C7 foramen transversarium is usually “empty,” this level is the most amenable to a pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO).

PATHOGENESIS

There are many etiologies of cervical kyphosis, including degenerative disease, trauma (acute and chronic onset), tumor, infection, inflammatory arthropathies, and iatrogenic causes.

Ankylosing spondylitis is the most common inflammatory cause.

Caused by contraction and ossification of the ligaments of the spine

Associated with the human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) haplotype in 80% to 90% of patients.

Iatrogenic causes include postlaminectomy kyphosis, pseudarthrosis, and postradiation syndromes.

NATURAL HISTORY

As there are many etiologies of cervical kyphosis, the natural history is quite variable.

In patients with fixed deformities, such as ankylosing spondylitis, the deformity may progress due to stress fracture or an unrecognized fracture, often indicated by an acute increase in the magnitude of the deformity or the level of pain.

As the axis of loading moves anterior to the vertebral body, the tendency is for progression of the deformity.

With more deformity, the spinal cord may become draped over the vertebral bodies, and the patient may become myelopathic, quadriparetic, or quadriplegic.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The chief complaint of the patient should be elicited. The patient may present with swallowing and/or breathing difficulties. Forward gaze is often affected. Patients may also note low back pain, as they hyperextend the lumbar spine to maintain a horizontal gaze.

The patient should be asked to stand with hips and knees extended, allowing for an accurate assessment of the deformity and sagittal balance.

Any sudden change in deformity or pain should be considered a fracture until proven otherwise.

An accurate history of previous cervical procedures is needed, as this is essential for preoperative planning.

The patient should be asked to lay supine to assess the rigidity of the deformity.

The gait should be observed for evidence of myelopathy. Other affected joints should be assessed to determine the need for treatment prior to addressing the cervical deformity.

The exam should include a full neurologic examination to check for evidence of myelopathy or spinal cord dysfunction.

All patients should undergo a full medical evaluation, as respiratory and gastrointestinal dysfunction are not uncommon in this population. In severe cases of respiratory compromise, a preoperative tracheostomy may be advisable.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographic evaluation should begin with anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and flexion/extension radiographs of the cervical spine (FIG 1A-F).

This allows for assessment of both the degree and flexibility of the deformity.

Standing AP and lateral radiographs of the entire spine, with the hips and knees in maximal extension, are obtained to assess global coronal and sagittal balance. We also obtain standing AP and lateral photographs to post in the operating room and to aid in planning correction.

A computed tomography (CT) scan with 1-mm cuts and sagittal, coronal, and three-dimensional reconstructions are obtained. This allows for assessment of the fusion mass and helps provide landmark guidance for instrumentation (FIG 1G).

If one is deciding between Smith-Petersen osteotomies (SPO) and a PSO, then careful evaluation of the disc spaces is necessary. If there is a circumferential fusion, a PSO is required.

An MRI is obtained to visualize the neural elements. If the patient cannot tolerate a closed MRI (sometimes precluded by the deformity), then an open MRI or CT myelogram may be obtained.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Degenerative disease

Inflammatory arthropathy

Ankylosing spondylitis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Posttraumatic kyphosis

Acute

Chronic

Infection

Tumor: includes intradural pathologies

Iatrogenic

Postlaminectomy

Pseudarthrosis

Postradiation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management of symptomatic cervical kyphosis is limited, as the patient has minimal compensatory mechanisms to maintain horizontal gaze.

Pain may be controlled with anti-inflammatory and narcotic medications.

Bracing of flexible deformities is not ideal, as any improvement in symptoms will only occur when the brace is worn. Bracing of fixed deformities is not possible. Chronic brace use runs the risk of pressure ulcer formation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management is necessary when the patient is suffering from respiratory compromise, has difficulty eating, or has significant difficulty maintaining horizontal gaze.

In many cases, correction of cervical kyphosis is an elective procedure that is performed when the patient can no longer tolerate the symptoms, most of which are not life threatening.

Preoperative Planning

All joints should be evaluated prior to a cervical osteotomy because hip and knee flexion contractures may require intervention prior to addressing the cervical spine.

Patients may present with concomitant thoracolumbar (TL) kyphosis, and a corrective osteotomy of the TL spine may be necessary. In this case, the TL procedure should be performed first, as horizontal gaze may correct with the TL osteotomy.8 If the cervical osteotomy is performed first, a subsequent TL osteotomy may leave the patient in a position with the head fixed in too much extension.

The chin-brow angle should be measured.

We also measure the angle of deformity with a midsagittal CT scan image. This allows for more accurate planning in severe deformities.

The goal of correction should be to create a chin-brow angle of approximately 10 degrees.

With the head in slight flexion, the patient is able to see both their feet and straight ahead.

We aim to align the posterior vertebral line of C2 with the anterior vertebral line of C7.

Although aesthetically pleasing to the layman, a neutral chin-brow angle is not well-tolerated by the patient, as they cannot see directly in front of their body.8

For smaller deformities, with only a posterior fusion, we may perform single or multiple SPOs. For larger deformities (>30 degrees) or circumferential fusion, we will perform a PSO.

Anterior osteotomies or a corpectomy, combined with a posterior approach, may offer impressive corrections, avoiding the increased risks associated with three column osteotomies.

Also, combined anterior/posterior approaches may be more appropriate for segmental kyphosis above C7.

Positioning

Gardner-Wells tongs are used to secure the head, and 15 pounds of traction is applied.

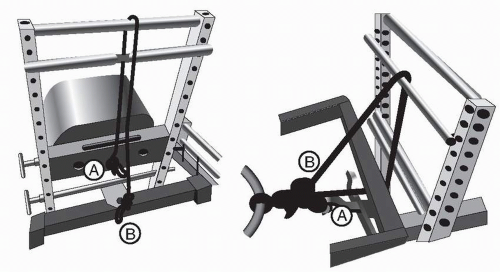

Bivector traction is applied through the frame. One vector pulls axially and is used to position the head until the osteotomy closure. At the time of closure, an extension moment is applied by switching the weight to the second rope which facilitates closure and holds the head in the appropriate position until the head is fixed in place (FIG 2).

We position the patient prone on a Jackson frame with a chest bolster, anterior iliac crest pads, and a leg sling. In the case of severe deformity, the chest bolster may be built up with pillows to allow appropriate positioning of the surgical field.

Although historically performed in a seated position, we prefer the prone position, as upper cervical implant placement is easier.7

The arms are wrapped with blankets at the patient’s side, and the elbows and wrists are padded.

Gentle traction is applied to the shoulders with tape.

The patient is placed in a maximal reverse Trendelenburg position. This brings the operative site into the surgeon’s field of view and allows for pooling of blood in the lower extremities.