Cervical Laminoplasty

Steven K. Leckie

James S. Kercher

S. Tim Yoon

DEFINITION

Cervical laminoplasty is a surgical technique first described in 19833 that allows for decompression of the cervical cord from a posterior approach. The procedure is designed to open and reconstruct the cervical lamina, thus creating more available space for the spinal cord while at the same time preserving motion and normal alignment.

Cervical spondylosis is a degenerative condition which can lead to multilevel spinal cord compression resulting in myelopathy. Congenital stenosis superimposed on spondylosis may predispose patients to myelopathy. Other conditions such as ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), trauma, infection, and neoplasm can also result in myelopathy.

The goal of laminoplasty is to alleviate circumferential compression of the spinal cord by decompressing the posterior aspect of the spinal canal and allowing the spinal cord to drift away from ventral compressive structures.

ANATOMY

The cervical spine is composed of seven vertebrae normally arranged in lordotic alignment. The occiput-C1 articulation is responsible for 50% of neck flexion and extension and the C1-C2 atlantoaxial articulation is responsible for 50% of total rotation. Lateral bending below the C2-C3 level is coupled with rotation due to the 45-degree inclination of the cervical facet joints.

The subaxial vertebral segments of C3-C7 are similar to each other and distinct from C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis). The subaxial vertebrae articulate via zygapophyseal (facet) joints posteriorly and uncovertebral joints of Luschka laterally.

Intervertebral discs are located between the vertebral bodies of C2-C7. The discs are composed of an inner nucleus pulposus and an outer annulus fibrosus.

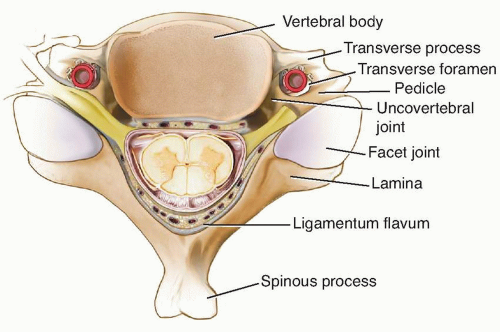

Anteriorly, the spinal canal is bounded by the vertebral bodies, the intervertebral discs, and the posterior longitudinal ligament. The pedicles form the lateral boundary of the spinal canal. Posteriorly, the ligamentum flavum runs from the anterior surface of the superior lamina to the posterior surface of the inferior lamina (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

Cervical spondylotic changes are the most common reason for cervical myelopathy.

Spondylosis is characterized by intervertebral disc desiccation and height loss, which leads to annular bulging and osteophyte formation around the uncovertebral and facet joints. In the dorsal spinal canal, thickening or buckling of the ligamentum flavum further decreases canal and foraminal cross-sectional area.

Circumferential spinal cord compression causes derangement at a cellular level, which leads to clinical deficits. In addition to static spinal cord compression, instability leads to motion that may aggravate myelopathy.

NATURAL HISTORY

There is a paucity of recent literature that documents the true natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy because modern practice is to perform a surgical decompression once significant myelopathy has been diagnosed. Early studies described a stepwise decline in neurologic function punctuated by stable periods, although some patients exhibited a continuous functional decline or no decline at all.

The clinical course may wax and wane over a period of years. Sensory symptoms may be transient, but motor symptoms tend to persist and progress. Although surgical intervention may relieve symptoms and halt progression, neurologic deficits may be permanent.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The diagnosis of cervical myelopathy may be difficult secondary to the variability in clinical findings. Pain is frequently not a significant complaint in myelopathic patients unless it is associated with root compression or facet arthrosis. Patients may present with subtle findings or profound neurologic deficits.

Patients commonly present with the insidious onset of gait disturbance, trouble with balance, and hand clumsiness. They may report burning pain in the upper extremities, difficulty with handwriting and fine motor control, diffuse

numbness, or weakness of grasp. Advanced cases can present with flaccid weakness or bowel and bladder dysfunction.

The physical examination should begin with an assessment of gait, which may be wide-based, hesitant, stiff, or spastic. Patients may be unable to walk heel-to-toe or may have poor balance during toe raise.

Sensory findings may be variable. Pain, temperature, vibratory, and light touch sensation may be decreased.

Mixed upper and lower motor neuron findings may be present depending on the degree of cord compression, concomitant nerve root compression, or peripheral nerve dysfunction.

The Lhermitte sign is positive when extreme neck flexion or extension results in electrical sensation down the arms or body and is a sign of spinal cord compression. Pathologic reflexes include the scapulohumeral reflex (indicating compression above the C3 level) or inverted radial reflex (indicating compression at C5 or C6). Other findings include the Hoffman sign, clonus (>3 beats), Babinski sign, slow grip and release, unsteady Romberg (posterior column), and abnormal finger escape (T1 level).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

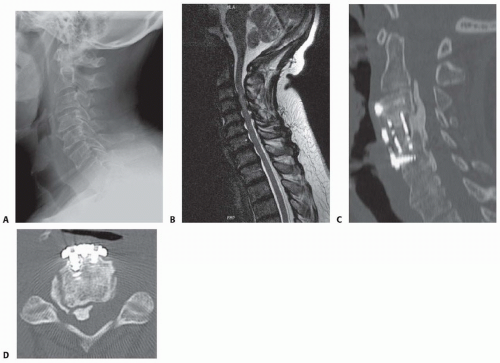

Plain anteroposterior (AP) and lateral standing radiographs of the cervical spine are useful for initial evaluation of sagittal alignment and the extent of spondylotic changes (such as disc space narrowing, osteophytes, kyphosis, joint subluxation, and spinal canal stenosis; FIG 2A).

Flexion and extension views provide information about possible spinal instability.

Typically, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing spinal cord compression. It can visualize the spinal cord and canal dimensions without any ionizing radiation. The spinal cord parenchyma can be visualized to help evaluate the extent of spinal cord damage. MRI is also useful for visualization of compressive soft tissue such as ligamentum hypertrophy and disc herniation (FIG 2B). Because it is usually obtained supine, MRI is less reliable than standing x-ray for evaluation of sagittal alignment.

Computed tomography (CT) is superior to MRI for defining bony anatomy and is useful for evaluating OPLL (FIG 2C,D). The addition of contrast dye myelogram combined with the CT (CT-myelogram) can improve the ability to assess spinal cord compression in the setting of previous hardware placement that would obscure an MRI with scatter artifact.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Stroke

Peripheral compression neuropathy (ie, carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel)

Parkinson disease

Muscular dystrophy or dystonia

Syringomyelia

Tumor

Vascular disease

Autoimmune disorders

Epidural abscess

Nerve injury

Drug intoxication

Multiple sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Cerebellar dysfunction

Idiopathic movement disorder

Peripheral neuropathy (B12 deficiency)

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Laminoplasty was specifically designed to decompress the spinal cord while avoiding the kyphotic deformities that had previously complicated laminectomy alone. Laminoplasty may be associated with fewer complications than laminectomy and fusion2,8 and has lower implant costs. It may also have fewer complications than multilevel anterior corpectomy.1

Laminoplasty creates effective posterior decompression of the subaxial cervical spine by allowing for dorsal cord expansion and drift while preserving motion.5 Dome laminectomy of C2 can be added if needed.

Theoretical advantages of laminoplasty over laminectomy and fusion include relative motion preservation, less soft tissue dissection, shorter operative time, diminished blood loss (in experienced hands), and less concern about smoking status and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use (which would increase the nonunion risk in fusion surgery).

Laminoplasty can be performed via open door (lateral opening trough with a single hinge) or French door (midline opening trough with bilateral hinges) techniques. Although the French door technique requires an additional hinge, it results in less epidural bleeding than the open door technique because the veins tend to be lateral. Both techniques are effective in treating myelopathy.7

Indications

Spinal stenosis due to either cervical spondylosis, congenital stenosis, or OPLL that results in multilevel cord compression and cervical myelopathy6

Contraindications

Kyphotic sagittal alignment of more than 10 to 14 degrees can lead to worsening of kyphosis and poor neurologic outcomes because the spinal cord is unable to drift back.

Significant segmental instability

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree