Causes of ROM Loss and Therapeutic Potential of Rehabilitation

A patient with a stiff frozen shoulder, an elderly patient with severe cervical spine degeneration and rotation loss, a stroke patient with hand–wrist contractures, a person with Dupuytren’s contractures and a patient with post-immobilization range of movement (ROM) limitation: who is likely to benefit from ROM rehabilitation and to what extent?

ROM loss is often the outcome of a condition but rarely its cause. Therapeutic outcome is determined largely by the potential for recovery of the causal condition. It also depends on the capacity of treatment to influence the resolution of the causal condition and its capacity to stimulate the adaptive mechanisms underlying ROM recovery. A patient with central nervous system (CNS) damage (cause) may develop contractures (outcome). Stretching the contracture (outcome) does not normalize the abnormal motor control which maintains the condition (cause). In this case stretching alone without motor rehabilitation is likely to be ineffective. On the other hand, frozen shoulder (cause) is associated with capsular contractures (outcome). Since frozen shoulder is a self-limiting condition it is expected that treating the outcome (shortening) will facilitate ROM recovery.1

Hence, identifying the cause and outcome and whether the underlying condition is self-limiting or persistent will have an impact on the treatment priorities, choice of management and the prognosis as well as managing the therapist’s and patient’s expectations. It is also essential for delimiting the clinical use of ROM rehabilitation.

This chapter will explore the following topics:

What are the common causes of ROM losses?

What are the common causes of ROM losses?

What physiological processes are associated with ROM losses?

What physiological processes are associated with ROM losses?

When is ROM rehabilitation useful?

When is ROM rehabilitation useful?

Defining the Boundary of ROM Rehabilitation

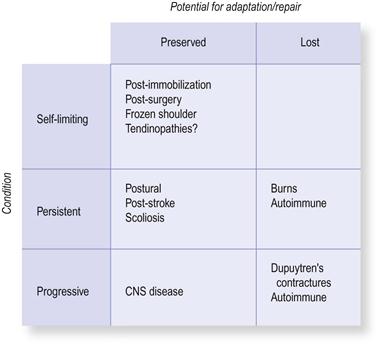

There are two key factors that determine whether ROM rehabilitation will be therapeutically useful (Fig. 3.1). The first consideration is the prognostic path of the causative condition: whether it is self-limiting, persistent or progressive. Another consideration is the condition’s potential for repair and adaptation as well as symptomatic relief: the three processes that underlie ROM recovery (Ch. 1). When these processes are preserved, ROM rehabilitation is likely to be more successful than in those conditions in which they are disrupted by the disease process.

Self-limiting conditions

Acute tissue damage is one of the most common self-limiting causes of ROM loss. In many forms of injury, tissue damage is not associated with tissue shortening or stiffening. The limitation in movement is often due to internal swelling within the affected tissues combined with a complex protective strategy that includes pain, increased sensitivity and motor reorganization of movement.2,3 Such acute ROM loss can be seen in delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) after exercise, a mild form of muscle damage.4 Stiffness and ROM losses develop very rapidly within days after exercising, last for a few days and recover fully in line with muscle repair. The patient’s subjective experience of stiffness/ROM loss is due to swelling and sensitivity and a loss in force production. Since in acute injuries there is no “true” shortening of tissues the therapeutic aim is to support the tissue repair processes. This can be facilitated by passive or active movement within pain-free ranges (see Ch. 9).5 Although stretching is widely used by therapists and athletes to treat ROM losses following acute injuries or DOMS, it is unnecessary and may even be detrimental.6,7

Inactivity or restricted movement range is another common cause of ROM losses. This outcome is often seen after prolonged disabling injuries, post-surgery and following immobilization. In this spectrum of conditions the ROM losses are an adaptive response, secondary to the underlying condition. The shortened, inextensible tissues often preserve their capacity for adaptation and therefore have a good potential to recover to a pre-injury state, depending on various factors such as the magnitude of damage (Ch. 4). In this group of conditions, ROM challenges are likely to be useful.

Between the self-limiting and persistent conditions are several conditions in which pain and sensitization give rise to the experience of stiffness and ROM loss; yet, there is no true shortening of the affected area (Ch. 9).8,9 This phenomenon is observed in many long-term conditions such as chronic back and neck pain,10,11 trapezius myalgia12,13 and many of the tendinopathies such as tennis elbow, plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinosis.14–18 In this spectrum of conditions, pain alleviation and desensitization may also be associated with adaptation within the nociceptive system. Stretching may have little or no effect on these processes and other forms of management should be considered, such as the use of relaxation or working with fear-related cognitions. This group of conditions and their management are discussed in more detail in Chapters 9 and 11.

Persistent conditions

Within the persistent group are ROM changes which are associated with behavioural, non-pathological conditions. There is a widely held belief that prolonged restrictive postural sets/behavioural patterns will result in tissue shortening. For example, some people believe that prolonged sitting with hunched shoulders will result in protracted scapula and shortened pectoral muscles. However, there is very little support for this from the sciences. It seems that even small breaks from the causal activity will offset or “normalize” these imbalances (Ch. 7).19 There are occasional exceptions, such as the association between regular wearing of high-heel shoes with shortening of the calf muscle and modest ROM restriction in the ankle.20

In this group of conditions the adaptive capacity is fully preserved. Hence, if such shortening is evident it can be easily resolved by modifying the causal activity, for example by wearing flat shoes or changing sitting posture. Traditional stretching methods are likely to be ineffective and short-lasting unless there is a concomitant change in movement behaviour. So some ROM recovery can just be about a change in behaviour.

Certain occupational and sports activities may also result in low-level ROM changes in specific joints and movement planes.21–24 These changes often represent positive, sport-specific ROM adaptations that are beneficial for optimum performance. For example, runners tend to have stiffer lower limbs, which is believed to be a positive adaptation related to movement economy.25 Similarly, baseball players may develop minor changes in scapular position and motion.26 In these forms of adaptation, tissue changes are often minor and unlikely to have a negative impact on daily activities. Importantly, there is no pathology here and it might be imprudent to interfere with such beneficial sport-specific adaptation. There is no clinical or physiological value in stretching and it may even reduce sports performance.27–32

Scoliosis also falls within the persistent category. Correction of this benign postural state has been the target of many failed manual and physical stretching approaches (it might be the time to give up).33 Post-surgical complications, severe adhesions and surgical shortening of tissue can result in permanent, non-progressive ROM losses. In such non-progressive conditions some ROM recovery may be possible, particularly if it is adaptive and secondary to the condition (such as from disuse). However, this recovery, too, depends on the extent of damage/repair and the tissues’ capacity for adaptation.

Non-progressive CNS damage, such as stroke and head trauma, can result in persistent dysfunctional movement control that may lead to joint contractures.34–40 It has been estimated that up to 6 hours of daily stretching is required to compete with the chronic neuromuscular drive that maintains the shortening (see competition in adaptation, Ch. 7).35 In these conditions the therapeutic focus should be on recovering motor control (cause). ROM rehabilitation is unlikely to be effective without such improvement.34 This can be exemplified in a case of a stroke patient who presented with severe hand and wrist contractures. Initially, his carer could only open the clenched fist by using full force and throwing her body weight behind it. This strategy was used for 5 years without any obvious improvement. Over a period of a few months he was taught to relax the arm and was eventually able to open the clenched hand fully without any stretching (but with some assistance). Interestingly, once this control was achieved he was able to permanently maintain the relaxed hand position throughout the day and night. So some ROM rehabilitation is about motor control rather than stretching.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree