Case Studies

John A. Feagin Jr.

Introduction to Case Studies 1 and 2

We have come a long way in understanding the role of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and the infinite pathology that can coexist or evolve. The “bone bruise,” the torn meniscus, the chondral defects, concomitant injuries, the progression of laxity, functional impairment, the natural history, and degenerative arthritis are all part of the evolution of our understanding of the tear of the ACL.

Not all cruciate ligament injuries are similar; patients are dissimilar, functional demands are different, and the natural history is only vaguely known. To Dale Daniel et al.1 and many others, we owe a huge debt for their efforts to define the natural history. To Steadman and Rodkey,2 Sherman et al.,3 Lubowitz and Grauer,4 and others, we owe gratitude for their courage in revisiting primary repair. The “healing response” has been a huge step forward. Not every ACL requires reconstruction. Even prostheses are making a reappearance for the low-demand knee. We must better identify the demands the patient expects to place on the injured knee and determine what we can and cannot do to restore the knee.

We must accept that the ACL tear occurs in a myriad of ways under a multitude of load demands and that the displacement of tibia on femur is quite variable at the instant of injury. Furthermore, compliance and expectation may determine outcome. We understand, then, that no two ACL-injured knees are the same, and the ACL-injured knee can be a complex conundrum worthy of keenest concern and attention to detail.

Dr. Jack Hughston (personal communication, 1972) challenged us vigorously on our use of “isolated” as it related to the ACL. He was correct to do so and we were na+ve in our thought process. The ACL is a central pivot. The force required to disrupt the ACL and the displacement at the time of injury usually implicates other anatomic constituents—the chondral surfaces, the supporting subchondral bone, the menisci, the patella, and the secondary ligamentous restraints. All are at risk at the instant of injury.

The elucidation of the pivot shift by Losee et al.5 has helped us to understand the complex translation and rotation, which duplicate the injury and the patient’s symptoms. The magnitude and frequency of this shift is also a key to future functional impairment and the natural history. The ACL should never be addressed simplistically or na+vely as isolated. The complexity of the ACL, the biomechanical implications of the central pivot, and the frequency of injury in sport have challenged us to the limits of our scientific method. The challenge has been a worthy one. What we have learned, how we have learned, and the application of our new knowledge are not only the reasons for this book, but the rationale for Case Study 1: the “isolated” ACL-injured knee.

Case Study 1

The “Isolated” Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Injured Knee

|

What do we mean by “isolated”?

The diagnosis and care of the compromised cruciate

History

An 18-year-old secondary school athlete who has lettered in three sports sustained a noncontact injury to his right knee as he cut to the left in the second football game of his senior year. He heard a “pop” and was unable to continue play. The team physician, an orthopaedic surgeon, examined the knee on the field and felt it was “loose.” Re-examination the following day in the office confirmed the on-field impressions. The following diagnostic clues and findings were recorded.

Physical Examination of 18-year-old Athlete

| Diagnostic Clues | Findings |

|---|---|

| Effusion | 3 (moderate) |

| Tenderness | Medial and lateral joint lines |

| Motion | Limited: 20 to 50 degrees |

| Lachman test | 6–mm (injured minus normal difference) |

| Varus/valgus laxity | Slight increase |

| Pivot shift test | Positive |

| Patella apprehension | Slightly positive |

| Gait | Antalgic: patient prefers crutches |

| Neurovascular | Intact |

| Radiographs | Negative except for effusion |

Comments

The history was straightforward and suggested a tear of the ACL. The patient was a dedicated, disciplined athlete, and was determined to continue recreational sports. Physical examination with a positive Lachman test and a positive pivot shift test is indicative of a tear of the ACL. Is manual examination enough? In today’s world, I prefer magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for a more complete three-dimensional anatomic diagnosis. Although we must learn to read our own images, the presence of a radiographer schooled in joint-specific pathology is invaluable. The attending physician should settle for no less than quality imaging read by a radiographer of experience with complete diagnostic detail.

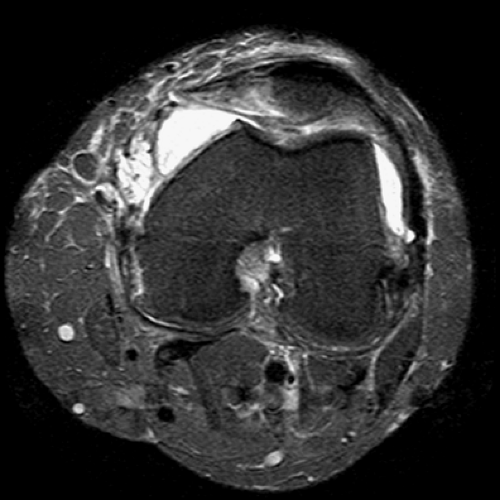

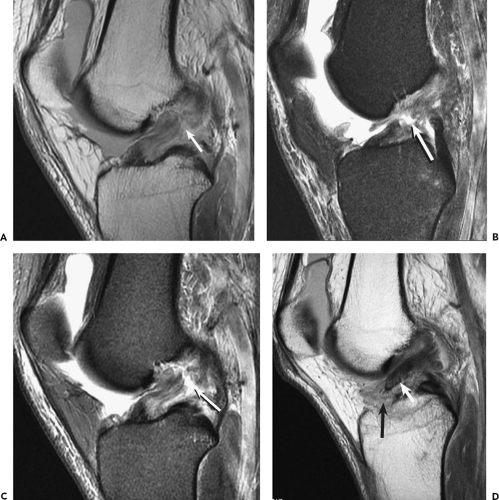

An MRI was obtained and showed a complete tear of the anterior cruciate ligament in its proximal third, a bone bruise of the lateral condyle and posterior tibia, and intact menisci. There were no obvious chondral lesions (Fig. 3.1.1).

The MRI was convincing. The patient and family wanted the knee repaired as soon as possible. They understood the implications of repair and rehabilitation.

Timing of the surgery is the next critical detail. The work of Shelbourne and Foulk6 and others in their group has brought great attention to this variable. I concur that it is usually in the best interest of the patient to perform the surgery on an elective basis after the effusion has resolved and motion has returned. The patient described in the history attended therapy diligently and was ready for surgery 2 weeks after the injury, with the effusion resolved and a near full range of motion. The examination before surgery confirmed a 6-mm injured-minus-noninjured knee Lachman result and a positive pivot test.

Figure 3.1.1 Tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) may be evaluated accurately for precise location and extent of the tear by magnetic resonance imaging (as shown in Figure 7.17). A: Sagittal proton density image shows complete disruption of the ACL (arrow) at the junction of middle and proximal thirds, with bowing and increased signal edema and hemorrhage within and about the proximal and distal tear ends. B: Sagittal fat-suppressed proton density image shows even more conspicuously the tear defect (arrow) and high-signal edema and hemorrhage. C: Sagittal fat-suppressed proton density image of a different patient reveals focal complete midsubstance tear of the ACL (arrow). D: Sagittal proton density image of another patient shows avulsion of the distal ACL attachment, with superior and posterior retraction and posterior rotation of the avulsed fragment (short arrow) of the ACL insertion with defect of the anterior tibial attachment (long arrow). |

Further Comments

The philosophy and technique of the physical examination were discussed in the chapter on physical examination. The principles I follow in the physical examination are as follows:

Examine the patient in the position of comfort.

Examine the well leg before the injured leg.

Examine (feel) gently for induration and tenderness.

Determine the status of the primary and secondary restraints.

Make an anatomic diagnosis.

Determine the envelope of pathologic motion through pivot shift testing and comparison with the well leg.

Examine standing alignment and evaluate gait. Be sure hip, ankle, and foot are included in the examination and that the neurovascular status is normal.

Special Considerations

The age of the patient is important, as it reflects his or her social responsibilities, lifestyle, maturation, and intended use of the limb. Adolescents and young adults rarely accept alterations in their lifestyle. Older patients will frequently adapt their lifestyle to their injury. The young adult’s wishes about surgery and restoration of function must be respected. Surgeons often ask at what age ACL reconstruction surgery should not be performed. I have not found a cutoff age because I know people in their 60s who would be quite disabled by an unstable knee. Nevertheless, one must recognize that older patients are likely to suffer complications. The surgeon should be prepared to modify both the plan, the operation, and the postoperative care accordingly.

There is often pressure to do the surgery immediately, although it is “far from home.” There are many considerations here, but the expertise of the surgeon, the quality of the rehabilitation, and the supervision must all be considered. Usually, surgery closer to home, where the supportive team is known, is more desirable. Continuity of care is essential and the operating surgeon is ultimately responsible for the end result.

Plan

What makes the practice of medicine unique is the infinite variability of “the plan.” We formulate the treatment plan by the subtle integration of all relevant factors—some obvious, some learned through experience, and some intuitive. The “best” treatment plan is the plan in which both the patient and surgeon have confidence. Perfecting this art of selecting the best treatment plan for each patient is an unending quest. The challenge is what keeps physicians vital through years of practice. Experience is important in formulating a treatment plan. Sometimes the surgeon is uncertain. Sometimes the patient is uncertain. Usually, I propose a tentative plan to the patient and then back off to allow response to the initial implications. I always let patients know that their input and insight are essential in formulating a plan for their care.

I have often found that my time is equally divided between the physical examination and formulating the plan with the patient. Ultimately, however, the physician is responsible for the contract made with the patient. If the patient finds it difficult to establish a firm contractural relationship, he or she should seek a second opinion. The surgeon should be quick to suggest further consultation when it is obvious the decision-making is difficult.

For this patient, a young dedicated athlete, the plan seemed relatively straight-forward—reconstruction of the ACL at the appropriate time with an extensive and thorough rehabilitation program to follow. Most patients wish to know which graft the surgeon is going to use. This level of sophistication is not uncommon and deserves respect. I explained to the patient that there are four choices: bone-patellar tendon-bone, hamstring grafts, allografts, and primary repair. I will usually end this brief discussion by expressing my preference for one of the four choices. This preference is not always the same. I frequently modify the choice of graft depending on the functional demands of the patient and certain anatomic features relevant to that patient. I also like to keep a window open for primary repair or “the healing response” (see Chapter 10), as I believe that sometimes this is the appropriate solution. I further explain that the final decision cannot be made until the time of surgery. Thus, I try to retain control of graft selection rather than allow the patient to pre-empt my experience on this matter.

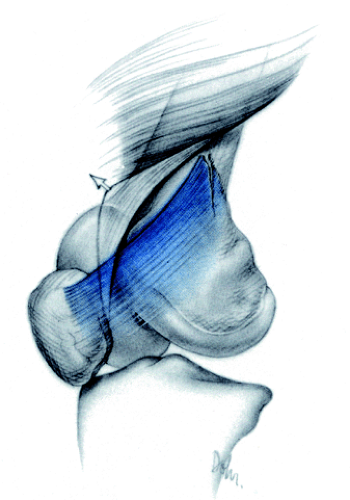

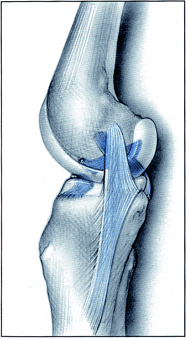

There are cases in which the patients decline surgery. This is their right. At this juncture, I usually encourage them to seek another opinion. Sometimes it is necessary to treat a patient nonoperatively for either medical reasons or as the result of the patient’s choice. For such a patient, I would consider immobilizing the knee in 20 degrees of flexion for 3 to 5 weeks. This course at least would have allowed the secondary restraints to begin healing and might have allowed the ACL to fall on the posterior cruciate ligament, and gain a secondary source of attachment and blood supply (Fig. 3.1.2). This mechanism was described by Wittek.7 This “repair,” however, is not anatomic and will not give satisfaction to a high-demand athlete.

Primary repair of the interstitially torn ACL is sometimes adequate. The work of Marshall et al.8 and Sherman et al.3 presents a good argument for primary repair when the repair is located proximally and the patient’s demands are minimal—age is not a discriminator. The interstitial nature of the torn helicoid ACL, the scant blood supply, and the hostile nature of the intercondylar notch all make it difficult to perform a primary repair that will restore vascularity and tensile strength. Augmentation grafting has been the procedure of choice for young patients with athletic demands.

Nevertheless, with improvement in MRI diagnosis and with an understanding that proximal tears do occur, especially in skiing, there has been a re-emphasis on primary repair and “healing response.” This is discussed by Dr. Steadman in detail in Chapter 8 of this book. To support the selectivity in the care of the patient, I have seen excellent results from both primary repair and the healing response. In retrospect, one third of the West Point Cadets that we reported in our original study9 did well with primary repair. This is especially noteworthy given the activity level of this patient population. Further reflection on this early report supports the need for selectivity in patient care.

Figure 3.1.2 The torn anterior cruciate ligament falls on the posterior cruciate ligament and thus gains a secondary source of attachment and blood supply. This drawing illustrates the results of immobilization but is similar to the outcome of a surgical repair technique used by Wittek.7 |

Surgical Procedure

The procedure for the patient described in this case study was as follows:

The knee was re-examined under anesthesia before the tourniquet was inflated. The difference between the well leg and the injured leg served as the criteria for restoration of stability after surgery. The patient was noted to have a positive pivot shift, which further indicated augmentation grafting.

Arthroscopic examination showed no meniscal pathology, no chondral defects, and an interstitially torn ACL. Bone-patellar tendon-bone grafting was accomplished (see Chapter 8).

After graft fixation, range of motion was checked and elimination of the pivot shift was confirmed.

A compression wound dressing was applied.

Postoperative Care and Rehabilitation

Immediate

There are three immediate postoperative goals:

Protection of the repair

Relief of pain

Prevention of adhesions

Continuous passive motion (CPM) has a function in achieving all three goals and has been an effective adjunct to knee surgery. Knowing that the joint can be moved comfortably so soon after the operation gives the patient confidence toward a home mobilization program. Intra-articular anesthesia has also served to relieve some of the postoperative pain and improve function. Epidural analgesia has also proved effective in speeding return of function and rehabilitation. These practices are discussed in more detail in Chapters 8 and 13. Outpatient surgery is performed frequently, although overnight stay has its advantages. What is essential is that control is gained of the patient, the pain, and the rehabilitation process.

The postoperative dressing is important to prevent swelling and minimize pulmonary embolism. Firm compressive dressing or elastic stocking with a Cryocuff (AirCast, Summit, NJ) is applied at the end of the operation and maintained for 7 to 10 days. The thigh-length antiembolic hose has proved most satisfactory. Care is taken not to impart venous constriction through an elastic bandage about the knee.

Pulmonary embolus is a paramount consideration even in young patients. The choice of postoperative brace is again surgeon-dependent and is discussed in Chapters 6 and 8.

Long Term

Long-term rehabilitation is perhaps the most neglected portion of patient management. Return to full function is the goal of the surgical procedure, but without rehabilitation, it will not be attained. Sir John Charnley once said that a perfect operation requires little rehabilitation (personal communication, 1972). I agree, but we are far from having a perfect knee operation. As we approach perfection, we will see a decrease in the demand for rehabilitation. Indeed, we have already seen an example of this trend as arthroscopic and limited incisional surgery have replaced the open surgery of yesteryear.

Common to all long-term rehabilitation programs are the goals of strength, endurance, and agility. The SAID principle (specific adaptation to individual demands) is also applicable. These goals should be explained to the patient and objective criteria for performance established. Rehabilitation is discussed in depth in Chapter 13.

Finally, there is return to competition. It is not necessarily national or even local competition. Sometimes it is self-competition, the drive to turn the clock back and “do it again” with vigor and commitment and without pain or giving way. This is the ultimate goal. We should prepare athletic patients, such as the one described here, to work gradually toward this goal—the restoration of lifestyle for a lifetime of usage. A gratifying and unifying event for patient and surgeon is “return to competition.”

Problems, Complications, Follow-Up Results

ACL surgery today is reliable to the 90th-plus percentile. Reinjury and retear do occur; they present serious problems. This is usually associated with a return to competitive sports and often reflects a reinjury of the magnitude of the original injury.

The other bedeviling complication is arthrofibrosis—limitation of motion and patellar capture. This complication has been under appreciated but is reflected in long-term morbidity. A flexed knee gait will not be accepted by the patient for long. Furthermore, capture of the patellofemoral joint through scar tissue, adhesions, and loss of the anterior interval take a toll on the patella through compression arthropathy. The physician must be alert to this complication, and be able to manage it through rehabilitation and/or arthroscopic debridement and release. I must counsel the patient both pre- and postoperatively regarding this possibility. Complications will be discussed in detail in Chapters 11 and 12.

Summary

This case involved an 18-year-old outstanding athlete who sustained an “isolated ACL” during an athletic competition. The patient elected surgical repair and the central third of the patellar tendon was used for augmentation grafting. A high level of confidence in this operation by close supervision and a thorough rehabilitation program is essential to success.

The long-term results for patients treated in this manner have been excellent. The operation has proved to be reproducible. Rehabilitation, both short-term and long-term, has been stressed until strength, endurance, and agility are restored. Bracing, return to competition, and complications are discussed in Part II of this book.

Case Study 2

The Multiligament-Injured Knee: Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear, Medial Collateral Ligament Tear, Peripheral Tear of the Medial Meniscus

|

The role of magnetic resonance imaging

The timing of surgery

Medial collateral ligament repair

Meniscal repair

History

A 21-year-old college junior, a first-string running back, was struck on his planted right leg while advancing the ball. He experienced severe pain and did not attempt to rise from the turf. The examination revealed gross laxity and he was helped from the field with the leg well-splinted.

Comments

This case represents the classic injury of American football as described by O’Donoghue.10 This “triad injury” became more frequent through increased efficiency of the helmet, contact below the waist (the “crack-back block”), and enhanced fixation of the shoe-turf interface. As both the speed of the game and the force of impact increased in the late 1950s, these injuries became all too common. Game films allowed analysis of the disruptive forces that were applied to the knee through this classic mechanism. Peterson (O’Donoghue Presentation at the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine meeting, Lake Tahoe, CA, 1981), through study of game films and the injury pattern, promulgated rule changes that have been responsible for a marked decrease in this devastating injury. Regretfully, though, these devastating injuries still occur with regular frequency.

Since this patient has a chance at a professional sport future, he would be called an “elite” athlete. The next season was important to both player and coach. Because of the serious nature of the injury and the future prospects, it is important that planning proceed expeditiously and thoroughly.

Course of Action

Physical Examination

Knee Examination of 21-year-old Collegiate Running Back

| Diagnostic Clues | Findings |

|---|---|

| Effusion | Mild |

| Tenderness | Medially |

| Lachman test | 8–mm (injured minus normal) |

| Drawer test | +3–mm positive; soft end point |

| Pivot shift test | Not attempted |

| Varus/valgus | 3+ valgus opening in full extension; stable in full extension to varus testing |

| Patellar apprehension | Patellofemoral joint stable but apprehension with lateral displacement |

| Range of motion | Too painful to elicit |

| Gait | Unable to bear weight |

| Neurovascular | Intact |

| Imaging | Joint effusion and medial swelling |

The on-field examination showed gross laxity, both to anteroposterior testing as well as medially. This indicated a multiligament-injured knee. In such cases, it is important to define the stable hinge when one exists. This allows the surgeon to plan surgery around the stable hinge.

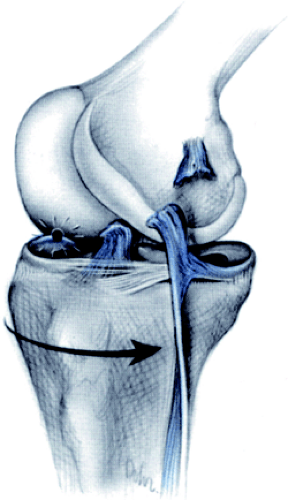

In this case, the stable hinge appeared to be lateral. MRI is essential in cases of this magnitude to define the extent of injury and plan the surgery (Fig. 3.2.1).

Although a pivot shift may be helpful to determine the extent of injury, it would have been unnecessary to subject this patient to a subluxation test without anesthesia. Finding the knee stable to varus testing in extension confirmed the integrity of the lateral capsular ligament and the posterior cruciate ligament.

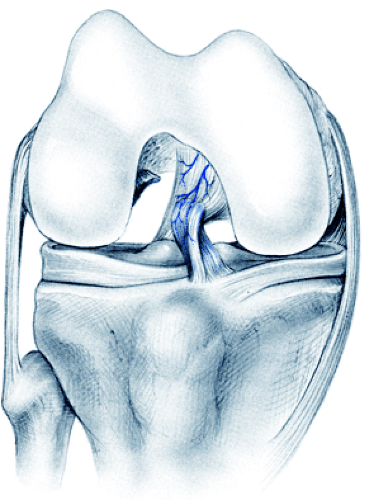

The patellofemoral mechanism can sometimes be disrupted in this injury. When this occurs, the lesion usually is at the origin, that is, the attachment of the superior medial patellofemoral ligament to the linea aspera and medial intermuscular septum (Fig. 3.2.2).

Diagnostic Studies

The routine radiographs were carefully studied for bony evidence of capsule or ligamentous avulsion. The MRI revealed a midsubstance interstitial tear of the ACL, an intact posterior cruciate ligament, tear of the medial collateral ligament, the posterior oblique ligament, and the medial meniscus. The lateral structures were intact. There was a bone bruise of the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 3.2.1)

Arthroscopy must be carefully performed because of the danger of extravasation of the fluid through the disrupted medial compartment and possible compromise of the compartments of the lower leg. Arthroscopy is important, however, to prepare the medial meniscus for repair as well as to assess the damage to the medial structures and lateral compartment.

One important evaluation is the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus. The subluxation of the tibia on the femur sometimes results in a Finochietto lesion (Fig. 3.2.3).11 This tear of the undersurface of the posterior horn, lateral meniscus, is important. At the time of arthroscopy in cases of this severity, I believe that the posterior compartment should be visualized through the intercondylar notch as further injury is often noted in this viewing, especially with a 70-degree oblique arthroscope.

Special Considerations

In injuries of this severity, I believe in early surgery. This usually occurs the morning after the game when the patient has been hydrated, re-evaluated, and counseled. The surgical team is important in that surgery must proceed rapidly and expeditiously and tourniquet time must be limited. For an assistant, I prefer an orthopaedic surgeon or highly trained surgical assistant who has experience in knee surgery cases. Because the equipment is also highly specialized, the surgical technician and operating room nurse are critical to the case. Fortunately, specialized surgical equipment exists to affix the ACL, the meniscus, and the torn ligaments. The patient must be counseled that internal fixation devices will be used and sometimes they require removal later. The patient should further be counseled about the importance of meniscal repair, wherever and whenever possible.

Plan

The patient was scheduled for surgery the morning after injury, and the knee had been amply iced as well as splinted immediately subsequent to the injury. The “first team” was assembled for the operative procedure. A detailed examination under anesthesia is important so that maximum use can be made of arthroscopic repair and the incisions minimized. All disrupted structures must be repaired. A diligent intraoperative physical examination at each stage of the repair will verify the restoration of stability and ensure that a ligamentous lesion has not been overlooked.

Examination under anesthesia is a part of the operative care. It is performed immediately after induction of anesthesia, before the leg is prepared, in comparison to the well leg, and before the tourniquet is inflated. Besides the obvious laxity, the surgeon searches particularly for induration at the posterior corners of the meniscal ligamentous complexes and the limits of motion of the joint anteriorly, posteriorly, and in rotation. The stable hinge is important to define. The C-arm should be available to the operating room to verify laxities and resolution of the appropriate surgery as necessary.

Surgical Procedure (Plan)

Complete interstitial tear of the ACL requires augmentation grafting. Frequently, in severe cases of this nature, I use an allograft to limit surgical dissection. The patient must be thus counseled as to this preference.

The meniscal attachments are carefully defined at arthroscopy. The meniscotibial and meniscofemoral attachments are important for stability. Definition of the posterior oblique ligament as it attaches to the meniscus must be determined and repaired. The question becomes, what is the most expeditious order to repair the components?

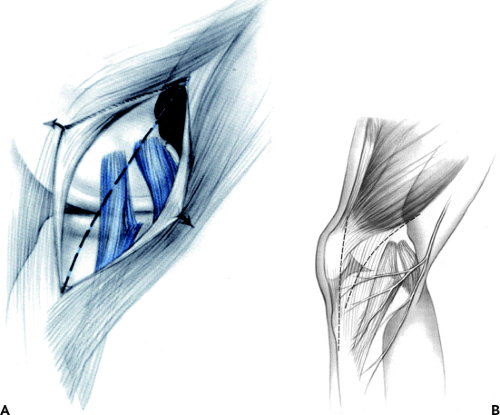

Furthermore, care must be taken to ensure that there are no chondral lesions, and if these are present, they should be addressed as appropriate to their extent and depth (see Chapter 9). It is obvious in this case that a limited incision will be required (Fig. 3.2.4A–B) in order to repair the medial collateral ligament and the posterior oblique ligament as well as the meniscotibial and meniscofemoral attachments. Some of this work can be done arthroscopically. This is to be encouraged wherever appropriate. Thus, the goal is an anatomic restoration of the torn structures and this usually requires some open surgery. The secret is to minimize the open surgery through preoperative planning enhanced by physical examination, MRI, and the diagnostic operative arthroscopy.

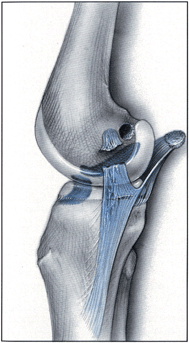

As regard to sequence of repair, I prefer to prepare the ACL tunnels for femoral and tibial insertion as a first step. Allograft will materially decrease postoperative morbidity. Then, prior to tensioning and fixation of the ACL, I address the meniscus and medial capsuloligamentous structures. Here it is important to define the posterior oblique ligament, which intimately attaches to the meniscus, from the medial collateral ligament, which is not attached to the meniscus. It is also important to restore the meniscotibial ligaments and their attachments of the semimembranosus. Repair of medial structures should be accomplished according to the theoretical course of the medial collateral ligament (the line of the Burmester curve), as described by Mueller (Fig. 3.2.5).12 Subsequent to repair of these structures, the ACL is tensioned and fixed. (For details, see Chapter 8.)

Postoperative Care and Rehabilitation

Tourniquet time should be minimized. In the postoperative course, pain is decreased when tourniquet time is kept to the minimal. Also, the muscle tissues and the neurovascular structures sustain minimal damage.

Patient postoperative pain is a major concern to the surgeon. Techniques for postoperative pain are discussed in Chapters 3 (Case Study 1) and 8. Compression bandage or elastic stocking is applied firmly. Cryotherapy is a critical component of postoperative patient care. Also, I prefer that the patient use continuous passive motion (CPM). We usually begin with 20 degrees to 70 degrees of motion. The patient is usually hospitalized for 1 or 2 days subsequent to the surgical procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree