Chapter 73 Capsicum frutescens (Cayenne Pepper)

Capsicum frutescens (family: Solanaceae)

Common names: cayenne pepper, capsicum, chili pepper, red pepper, American pepper

Chemical Composition

Chemical Composition

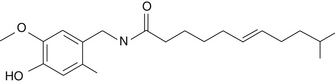

The most important constituents of cayenne pepper are the pungent compounds, with capsaicin being the most prominent (Figure 73-1). Typically, cayenne pepper contains about 1.5% capsaicin and related principles. Other active constituents present include carotenoids, vitamins A and C, and volatile oils.

History and Folk Use

History and Folk Use

The folk use of cayenne pepper is quite extensive. It has been used for the following:

It has also been used as a counterirritant in the topical treatment of arthritis and neuralgia.

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

The pharmacology of cayenne pepper centers around its capsaicin content. Interestingly, capsaicin, although hot to the taste, has actually been shown to lower body temperature by stimulating the cooling center of the hypothalamus.1 The ingestion of cayenne peppers by cultures native to the tropics appears to offer a way for these people to deal with high temperatures.

When taken internally, cayenne pepper exerts a number of beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system. In addition to possessing several antioxidant compounds, studies have shown that cayenne pepper reduces the likelihood of developing atherosclerosis by reducing blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels and platelet aggregation, as well as increasing fibrinolytic activity.2–4 (For the significance of these effects, see Chapter 148.) Cultures consuming large amounts of cayenne pepper have a much lower rate of cardiovascular disease.

When topically applied to the skin or mucous membranes, capsaicin is known to stimulate and then block small-diameter pain fibers by depleting them of the neurotransmitter substance P.5 Substance P is thought to be the principal chemomediator of pain impulses from the periphery. In addition, substance P has been shown to activate inflammatory mediators into joint tissues in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.6

Clinical Applications for Oral Preparations

Clinical Applications for Oral Preparations

Cayenne pepper exerts several beneficial effects on gastrointestinal function, including acting as a digestant and carminative.7 Double-blind studies showed that red pepper consumption protects against aspirin-induced stomach damage and improves epigastric pain, fullness, and nausea scores in people with nonulcer dyspepsia.8–10 In one study, the digestive-enhancing effects of capsicum were determined in 30 patients with functional dyspepsia and without gastroesophageal reflux (GER) disease and irritable bowel syndrome.11 These patients received, before meals, randomly and in a double-blind manner, 2.5 g/day of red pepper powder or placebo for 5 weeks. The overall symptom score and the epigastric pain, fullness, and nausea scores of the red pepper group were significantly lower than those of the placebo group, starting from the third week of treatment. The decrease reached about 60% at the end of treatment in the red pepper group, whereas placebo scores decreased by less than 30%.

Capsicum does, however, lower the threshold for GER, presumably by direct effects on sensory neurons and may produce symptoms of GER.12,13

Thermogenic Aid

Capsicum ingestion may also prove to be helpful in promoting weight loss in obese individuals, because clinical studies showed capsicum increased the basal metabolic rate while reducing appetite and caloric intake.14,15 In one study, after ingesting a standardized dinner on the previous evening, the subjects ate one of the following for breakfast: a high-fat meal, a high-fat meal with red pepper (10 g), a high-carbohydrate meal, or a high-carbohydrate meal with red pepper (10 g). Diet-induced thermogenesis was significantly enhanced by the addition of red pepper to either meal, but especially the high-fat meal.16 In another study, 40 women and 40 men (mean age of 42 years and body mass index of 30.4) were randomly assigned to a capsinoid (6 mg/day) or placebo group.17 Mean weight change was 0.9 and 0.5 kg in the capsinoid and placebo groups, respectively. There was no significant group difference in total change in adiposity, but abdominal adiposity decreased more in the capsinoid group (−1.11%) than in the placebo group (−0.18%), and this change correlated with the change in body weight. Changes in resting energy expenditure did not differ significantly between groups, but fat oxidation was higher at the end of the study in the capsinoid group.

Atherosclerosis and the Metabolic Syndrome

Capsicum exerts a number of effects beneficial in the prevention of atherosclerosis, including inhibiting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation, acting as an antioxidant, inhibiting platelet aggregation, promoting fibrinolysis, and improving arterial function.18 Chili consumption also lowers postprandial hyperinsulinemia.19

Clinical Applications for Topical Preparations

Clinical Applications for Topical Preparations

Postherpetic Neuralgia

In general, the results of this study were consistent with other studies (i.e., about 50% of people with postherpetic neuralgia responded to topically applied capsaicin [0.025%]).16,20–24 Although this might not be a great response, it was better than the 10% response noted in the placebo group. Higher concentration (0.075% vs 0.025%) might produce better results (as high as 75% response).25 Another study showed that capsaicin responders were characterized by higher average daily pain, higher allodynia ratings, and relatively preserved sensory function at baseline compared with nonresponders. In three of the “capsaicin responders,” the area of allodynia expanded into previously nonallodynic and nonpainful skin that had normal sensory function and cutaneous innervation.26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree