Chapter 1 CAM Use in Illness and Wellness

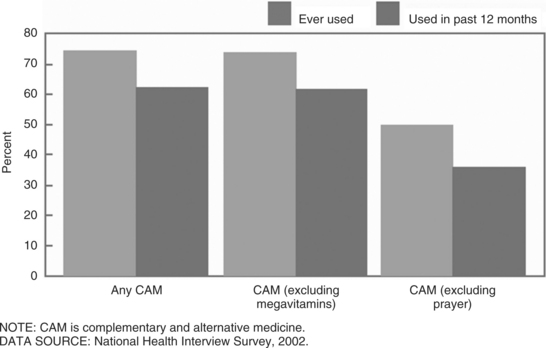

Over the past 15 years complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) or therapies have exploded in their popularity and use.1–3 In the United States, people across the lifespan are reporting use of CAM for wellness and illness.1,4 Efforts to characterize and study CAM were formalized in the United States through the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) and now the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM).5 Research to determine the efficacy and effectiveness of CAM also has exploded (Figure 1-1).6 Given the population’s increased use of CAM in addition to the mounting efforts to study CAM, physical therapists ought to be aware of CAM use and the evidence to support it.

Figure 1-1 Clinical trials and review studies in CAM. The volume of literature in CAM has increased over the past 10 years. Notice the fourfold increase in clinical trials from 1995 to 2005. Ernst et al.6

DEFINITIONS OF COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

Complementary and alternative therapies have been defined in various ways. These definitions have evolved as our understanding and study of the field have been refined. The definitions of complementary and alternative therapies vary with the organization that defines them and shift over time. In 1999 NCCAM described CAM as treatments and health care practices not taught widely in medical schools, not generally used in hospitals, and not usually reimbursed by medical insurance companies.”7 This definition was acknowledged to be broad and evolving.8 For that reason, in 2007 NCCAM defined CAM “…as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine. Conventional medicine is medicine as practiced by holders of M.D. (medical doctor) or D.O. (doctor of osteopathy) degrees and by allied health professionals, such as physical therapists, psychologists, and registered nurses.”

Integrative medicine is the third term that requires a definition. It was described by Weil in 2000 as healing-oriented medicine that draws upon all therapeutic systems to form a comprehensive approach to the art and science of medicine. Integrative practices are the appropriate use of conventional and alternative methods to facilitate the body’s innate healing response in consideration of all factors that influence health, wellness, and disease. Weil’s 2000 definition, originally posted on the University of Arizona Integrative Medicine website in September 2000, is no longer available. More recently, in 2007, the following definition can be found: “Healing-oriented medicine that takes account of the whole person (body, mind, and spirit), including all aspects of lifestyle. It emphasizes the therapeutic relationship and makes use of all appropriate therapies, both conventional and alternative.”9 Integrative medicine neither rejects conventional medicine nor accepts alternative medicine uncritically. As mentioned earlier, definitions of CAM change as the field develops.

The Samueli Institute advises health care professionals and health policy planners on important research questions regarding complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine. As an in-dependent scientific adviser, the Institute strives to provide research that is unbiased, based on evidence, and grounded in science. The Institute sponsored a conference to address definitions and standards of healing. The goal was to focus on establishing sound definitions to operationalize terms for research. The unifying construct of their work was using the term healing. Their work provides an additional dimension along which we can define, study, and integrate across healing practices.10

The process of defining CAM is an evolving one. Therapies previously considered alternative may move along the continuum to become complementary and then integrative. For example, 15 years ago, acupuncture may have been considered an alternative therapy based on a definition not taught or commonly found in hospitals. Today acupuncture theory and rationale for referral are taught in medical schools11 and offered in hospitals. The reason for this change is partially a landmark report by a consensus panel convened by the NIH that concluded that clear evidence exists of acupuncture efficacy for postoperative and chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, for nausea of pregnancy, and for postoperative dental pain. The NIH panel also cited other conditions for which acupuncture may be effective as a stand-alone or an adjunct therapy, but for which less convincing scientific data exist. These other conditions included drug addiction, stroke rehabilitation, headaches, menstrual cramps, tennis elbow, low back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and asthma. This consensus report has served as one of the most significant government statements that has contributed to increased acceptance of acupuncture and Oriental medicine by the biomedical profession in the United States.12

CATEGORIES OF CAM

A definition and example of each domain follows, but for more detail the reader is referred to the specific chapters in this book or the NIH NCCAM Backgrounder Series, found on the NCCAM website. Whole medical systems (see Chapter 4) “involve complete systems of theory and practice that have evolved independently from or parallel to allopathic (conventional) medicine.”13 Examples of whole medical systems are traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Ayurvedic medicine, Native American medicine, homeopathy, and naturopathy. Mind-body therapies (see Chapter 7) “focus on the interactions among the brain, mind, body, and behavior, and on the powerful ways in which emotional, mental, social, spiritual, and behavioral factors can directly affect health. They regard as fundamental an approach that respects and enhances each person’s capacity for self-knowledge and self-care, and it emphasizes techniques that are grounded in this approach.”14 Biologically based practices (see Chapter 10) use substances found in nature that include, but are not limited to, botanicals, animal-derived extracts, vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids, proteins, prebiotics and probiotics, whole diets, and functional foods. Some examples include herbal products and the use of other so-called natural but as yet scientifically unproven therapies (e.g., using shark cartilage to treat cancer).15 Energy-based therapies (see Chapter 13) deal with veritable (can be measured) and putative (have not yet been measured) energy fields for healing. Examples of veritable energy fields are sound, light, and electromagnetic forces. Putative, also called biofield energies, are subtle energy forms that can be found in nature and people. Examples of putative energy fields originate from whole medical systems such as qi in TCM and prana in Ayurveda.16 Manipulative and manual body-based therapies (see Chapter 18) deal with modification of the structure of the human body to improve function. Examples of manual body-based therapies are osteopathy, chiropractic, massage, and body work.17

REPORTED USE OF CAM

Prevalence of CAM use in addition to the specific conditions and reasons people chose to use CAM are relevant information for the physical therapist. Incorporating questions about CAM use into the client’s interview seems essential given the widespread use of CAM for recovery from illness and promotion of wellness. The belief about various types of CAM serves as a window into the client’s perspectives about health that may affect the outcome of the physical therapy intervention. For example, a client may use glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate as a supplement for knee osteoarthritis (OA). Proper education about nutrition and supplements in relation to the degree of OA is important to address during the course of physical therapy.

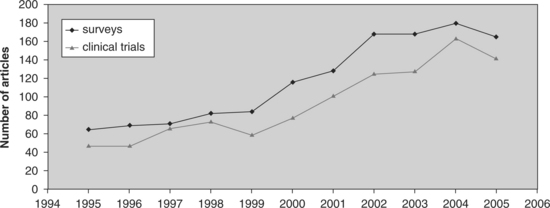

Reports of CAM use in the United States and many other Western countries have proliferated. Use is reported for the population at large1–4 and for specific groups such as the elderly18 and client populations such as people with multiple sclerosis,19,20 Parkinson’s disease,21 and children with asthma.22 Reported CAM use in the United States grew from a prevalence of 34% to 47% of the population between 1990 and 1997.2 According to Tindle et al, that growth stabilized in 2002.3 However, data from the CDC survey suggest otherwise, with reports of 62% prevalence.4 Use of specific therapies has either increased from 12.1% to 18.6% for herbals or decreased from 9.9% to 7.4% for chiropractic.3 Whether prevalence of use is increasing or not, millions of Americans are reporting use of CAM (Figure 1-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree