Calcaneus Fractures

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Calcaneus fractures account for approximately 1% to 2% of all fractures.

The calcaneus, or os calcis, is the most frequently fractured tarsal bone.

Represents 60% of all tarsal fractures in adults

Annual incidence of calcaneal fractures is 11.5 per 100,000 people.

The male to female ratio is 2.4:1.

Peak incidence is in males aged 20 to 29.

Displaced intra-articular fractures comprise 60% to 75% of calcaneus fractures. Approximately 10% of calcaneus fractures are open injuries.

Approximately 70% of calcaneal fractures resulted from falls.

ANATOMY

The articular surface contains three facets that articulate with the talus. The posterior facet is the largest and constitutes the major weight-bearing surface. The middle facet is located anteromedially on the sustentaculum tali. The anterior facet is often confluent with the middle facet.

Between the middle and posterior facets lies the interosseous sulcus (calcaneal groove), which, with the talar sulcus, forms the sinus tarsi.

The sustentaculum tali support the neck of the talus medially; it is attached to the talus by the interosseus talocalcaneal and deltoid ligaments and contains the middle articular facet on its superior aspect. The flexor hallucis longus tendon passes beneath the sustentacular tali medially.

The peroneal tendons pass laterally between the calcaneus and the lateral malleolus.

The Achilles tendon attaches to the posterior tuberosity.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Axial loading: Falls from a height are responsible for most intra-articular fractures; they occur as the talus is driven down into the calcaneus, which is composed of a thin cortical shell surrounding cancellous bone. In motor vehicle accidents, calcaneus fractures may occur when the accelerator or brake pedal impacts the plantar aspect of the foot.

Twisting forces may be associated with extra-articular calcaneus fractures, in particular fractures of the anterior and medial processes or the sustentaculum. In diabetic patients, there is an increased incidence of tuberosity fractures from avulsion by the Achilles tendon.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Patients typically present with moderate to severe heel pain, associated with tenderness, swelling, heel widening, and shortening. Ecchymosis around the heel extending to the arch is highly suggestive of calcaneus fracture. Blistering may be present and results from massive swelling usually within the first 36 hours after injury. Open fractures are rare, but when present, they occur medially.

Careful evaluation of soft tissues and neurovascular status is essential. Compartment syndrome of the foot must be ruled out because it occurs in up to 10% of calcaneus fractures and may result in clawing of the lesser toes.

Associated Injuries

Up to 50% of patients with calcaneus fractures may have other associated injuries, including lumbar spine fractures (10%) or other fractures of the lower extremities (25%); intuitively, these injuries are more common in higher energy injuries.

Bilateral calcaneus fractures are present in 5% to 10% of cases.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

The initial radiographic evaluation of the patient with a suspected calcaneus fracture should include a lateral view of the hindfoot, an anteroposterior (AP) view of the foot, a Harris axial view, and an ankle series.

Lateral radiograph

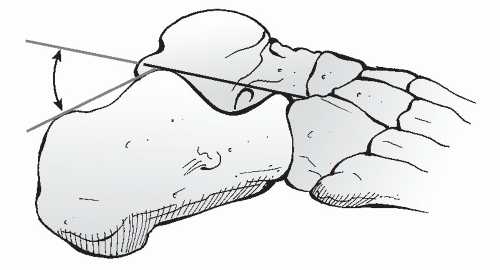

The Böhler angle is composed of a line drawn from the highest point of the anterior process of the calcaneus to the highest point of the posterior facet and a line drawn tangential from the posterior facet to the superior edge of the tuberosity. The angle is normally between 20 and 40 degrees; a decrease in this angle indicates that the weight-bearing posterior facet of the calcaneus has collapsed, thereby shifting body weight anteriorly (Fig. 39.1).

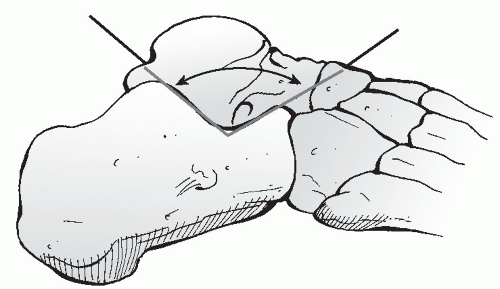

The Gissane (crucial) angle is formed by two strong cortical struts extending laterally, one along the lateral margin of the posterior facet and the other extending anterior to the beak of the calcaneus. These cortical struts form an obtuse angle usually between 105 and 135 degrees and are visualized directly beneath the lateral process of the talus; an increase in this angle indicates collapse of the posterior facet (Fig. 39.2).

AP radiograph of the foot: This may show extension of the fracture line into the calcaneocuboid joint.

Harris axial view

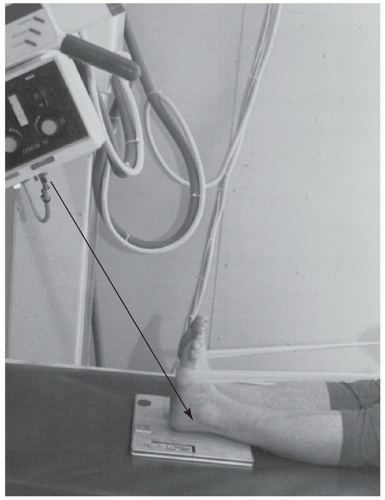

This is taken with the foot in dorsiflexion and the beam angled at 45 degrees cephalad.

It allows visualization of the joint surface as well as loss of height, increase in width, and angulation of the tuberosity fragment, usually in varus (Fig. 39.3).

Broden views have been replaced by computed tomography (CT) scanning. They are utilized intraoperatively to assess reduction. These are obtained with the patient supine and the x-ray cassette

under the leg and the ankle. The foot is in neutral flexion, and the leg is internally rotated 15 to 20 degrees (Mortise). The x-ray beam is then centered over the lateral malleolus, and four radiographs are made with the tube angled 40, 30, 20, and 10 degrees toward the head of the patient.

These radiographs show the posterior facet as it moves from posterior to anterior; the 10-degree view shows the posterior portion of the facet, and the 40-degree view shows the anterior portion.

Computed tomography

CT images are obtained in the axial, 30-degree semicoronal, and sagittal planes.

Two- to 3-mm slices are necessary for adequate analysis.

The coronal views provide information about the articular surface of the posterior facet, the sustentaculum, the overall shape of the heel, and the position of the peroneal and flexor hallucis tendons (Fig. 39.4).

The axial views reveal information about the calcaneocuboid joint, the anteroinferior aspect of the posterior facet, and the sustentaculum.

Sagittal reconstruction views provide additional information on the posterior facet, the calcaneal tuberosity, and the anterior process.

FIGURE 39.1 The Böhler angle. (From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.) |

FIGURE 39.2 Angle of Gissane. (From Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, et al., eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.) |

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|