According to the American Burn Association, a burn of any depth to the hand is classified as a major injury that requires treatment at a specialized burn center. However, therapists may see clients with burns in a variety of clinical settings after acute management of the injuries. Burn injuries are caused by thermal, chemical, or electrical action. The causes are numerous and include house fires, motor vehicle accidents, and contact with an electrical current or hot objects or liquids at home or at work.1,2 Along with their effect on hand function, burns can have a significant impact on a person’s social and psychologic functioning.4 Scarring, perceived disfigurement, and loss of control over the body and the environment may lead to significant body image changes, social avoidance, anxiety about the future, and hopelessness.5 Reduced income and reluctance to discuss emotions may also be contributing factors.6 Other psychologic symptoms that commonly develop after a burn injury are sleep disturbances, depression, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress.7 Related cognitive, emotional, and physiologic problems (such as, lack of concentration, apathy, pain, and low energy) can influence the client’s recovery, making it difficult for the client to comply fully with treatment. Significant others are also affected and have concerns of their own.8 The skin is the largest organ of the human body. Its essential functions include providing protection against bacterial invasion, preventing excessive loss of body fluids, regulating body temperature through perspiration, shielding deep structures from injury, absorbing certain substances (for example, vitamin D), and receiving sensory feedback from the environment.9–11 Without the protection skin affords, exposed underlying tissues (for example, muscle and tendon) become desiccated, and nerve endings are exposed. An important nonphysiologic function of the skin is to provide a cosmetic covering of the body that is unique to each individual. The delicate balance of the intrinsic and extrinsic musculotendinous systems also can be affected by a burn injury.3 The temperature and duration of exposure to heat and the characteristics of the skin burned determine the amount of tissue destruction. Burn injuries are classified by both depth and extent. The larger and deeper the burn, the worse the prognosis.13,14 Other factors include premorbid diseases and associated trauma.13 Burn depth is assessed by visual examination to determine the extent of damage to or the destruction of anatomic structures. Depth can be described by degree (that is, first, second, third, or fourth) or by thickness (superficial partial thickness, deep partial thickness, full thickness, and full thickness burn with subdermal injury); thickness is the more descriptive and contemporary method (Fig. 34-1). Because skin thickness varies, a burn to the hand may involve tissues at different depths. Precaution. A deep partial thickness burn may convert to a full thickness burn. A full thickness burn with subdermal injury (which corresponds to a fourth-degree burn) involves deep tissue damage to fat, muscle, or possibly bone. Electrical burns often cause this type of injury. These burns require extensive debridement of necrotic tissue, followed by skin grafting. Amputation may be necessary if the damage is too extensive and severe.10,14 The extent of a burn is determined by estimating the percentage of the body surface burned. The two methods used for this are the rule of nines and the Lund-Browder chart. The extent of injury is described as the percentage of the total body surface area (TBSA) burned. A rough estimation is that the palm of the client’s hand represents approximately 1% of the client’s body surface. Each side of the hand is considered 1.5% of the body surface; therefore a person with circumferential burns to both hands would have a 6% TBSA burn.15 The objective with any wound, including a burn, is to obtain quick healing to minimize scar formation and associated sequelae. The length of time required for wound closure is the most important determinant of scar development. Age, genetics, and burn depth and location are other variables.16 Wound healing is a dynamic cellular process that consists of three overlapping phases. Phase 1, the inflammatory (or exudative) phase, is characterized by inflammation and the presence of neutrophils and macrophages, which are responsible for clearing debris and preparing the wound for repair. This phase begins when the wound occurs and lasts 3 to 5 days. Phase 2, the fibroblastic (or proliferative or reparative) phase, lasts 2 to 6 weeks. It is characterized by the presence of fibroblasts, which lay down collagen and myofibroblasts, which cause wound contraction. The newly formed epithelium is very thin and fragile, and the tensile strength of the wound increases with collagen proliferation. Collagen is deposited in a random, disorganized fashion. Wound contraction continues even after epithelialization but to a lesser degree. Phase 3, the maturation (or remodeling) phase, may last for years. Collagen continues to cross-link, and tensile strength increases progressively.17,18 Typically, 50% of normal tensile strength has been regained by 6 weeks, and the ultimate tensile strength is only about 80% of that of normal skin.17,19 As scars mature, collagen deposition slows, and the breakdown of excessive collagen proceeds until scar maturity is reached. Hypertrophic scars may develop after burns, with a reported prevalence rate of 32% to 72%.7 Risk factors include dark skin, burns to the upper limb, burn severity, time to heal (longer than 3 weeks), and multiple surgical procedures. Hypertrophic scars are raised, thick, red, tight, and itchy. They also contract, often with deforming force. Scars that cross joints are the most problematic, because scar contraction can lead to loss of functional joint mobility. Scar hypertrophy and contraction are most active for the first 4 to 6 months.20 Clients with full range of motion (ROM) early on may lose motion in the ensuing months; therefore long-term follow-up therapy is needed. Scars that soften over the first 6 to 12 months have an improved prognosis for full joint function.14 As long as scars are active, they may be responsive to intervention with conservative therapy. Once scars have matured, surgical intervention is required to improve ROM or cosmetic appearance. Four overlapping phases of recovery have been described for burn injuries: (1) emergent, (2) acute, (3) skin grafting, and (4) rehabilitation.20 The emergent phase comprises the first 2 to 3 days after injury. The acute phase is considered to be the interval from day 2 or 3 to wound closure, which can occur by spontaneous healing or surgical intervention. The skin grafting phase is the period during which grafting is performed to cover wounds in the acute phase or as a component of reconstructive surgery in the rehabilitation phase. The rehabilitation phase lasts from wound closure to scar maturity. The course of treatment is influenced by the depth and extent of the burn injury, the client’s medical status, the stage of wound healing, and the physician’s plan of care. Nonsurgical management is an option for partial thickness burns, because they are able to regenerate epithelium.3,10,20 Treatment is aimed at preventing infection, promoting healing, and minimizing complications. Dressings are used to protect the wound and provide an optimum environment for healing. Dressings may be the adherent or non-adherent type, and they can serve a number of purposes, including infection control, comfort, wound immobilization, fluid absorption, debridement, and early pressure.13,17 Numerous dressing products and wound care/dressing change schedules are available. The selection of dressings and topical agents depends on the type and status of the wound; it also is often influenced by the physician’s preference. Therapists must work closely with the physician so that they fully understand the dressing program and the rationale for it. Positioning is important in the early phases of burn recovery to minimize edema, because edema can cause ischemia, intrinsic muscle tightness, deforming positions, loss of motion, adhesions, and fibrosis. Edema is a natural component of the wound healing process, and burns create local and systemic responses.21 Postburn edema develops rapidly within the first hour, peaks up to 36 hours after injury, and usually resolves within 7 to 10 days.20 Edema still present in later stages is a matter of great concern. Precaution. To prevent a decrease in arterial flow to the hand, elevate the hand to heart level only in the emergent phase.20 Orthoses can be used to facilitate wound healing by immobilizing the wound and protecting key structures in the hand. It is important to note that not all hand burns require orthotic intervention. The decision to use an orthosis or not depends on the depth and extent of the burn and the client’s ability to tolerate positioning, exercise, and function. Most superficial partial thickness burns do not require an orthosis, because healing is completed within 3 weeks. An orthosis should be considered if healing is compromised, or there is a significant limitation in active extension or flexion of hand joints.20 In some cases an orthosis may be indicated for a client who is unable to actively move the hand or for a client who may move too aggressively. Orthoses are used more often with deeper burns. Despite static orthotic intervention in the early phases of wound healing to prevent burn scar contracture, the incidence of contracture has been reported as 5% to 40% with weak evidence supporting their effectiveness.22 Unless otherwise indicated, immobilize the hand with the wrist in extension, the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints in flexion, the interphalangeal (IP) joints in extension, and the thumb in abduction. Slight wrist extension encourages MP flexion by means of a tenodesic effect, and MP flexion in turn puts tension on the collateral ligaments to prevent shortening. Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint extension protects the vulnerable extensor mechanism, and thumb abduction maintains the first web space. Considerable variation in ideal joint angles can be found in the literature.23 A consensus calls for wrist extension of 15° to 30°, MP flexion of 50° to 80°, full IP extension or slight flexion, thumb abduction midway between radial and palmar abduction, MP flexion of 10°, and full thumb IP extension (Fig. 34-2).10,16,20 For isolated burns to the palmar surface, position the wrist in neutral to slight extension, the IP joints in full extension and abduction, and the thumb in radial abduction and extension.20 Never force joints into the ideal position. Although prefabricated orthoses are available, custom orthoses made from perforated material are preferable because they allow a more precise fit and can be adjusted to accommodate changes in edema and joint mobility. Orthoses can be secured by gauze wraps, elastic bandages, or straps. Precaution. Carefully monitor and adjust how the orthosis is secured to ensure there is no vascular compromise.20 For clients with significant involvement of the IP joints, the surgeon may opt to place Kirschner wires across the joints to obtain complete immobilization and protection of the extensor mechanism.3 Orthoses may also be used in the later phases of recovery to prevent or correct scar contracture. To prevent contracture, use static orthoses, placing joints in positions opposite the direction the scar will pull. Common burn scar contractures in the hand are wrist flexion from volar burns, wrist extension or flexion from dorsal burns, thumb adduction from a burn to the first web space, MP and IP extension from dorsal hand burns, and MP and IP flexion from volar hand burns. Have the client wear the static orthosis at night only, if possible, to avoid compromising functional hand use during the day. Use serial static dynamic orthoses (also known as elastic mobilization) or static progressive orthoses (also known as inelastic mobilization) to regain ROM with joint and/or scar contracture. Place scars under tension in an elongated position to promote new cell growth, collagen remodeling, and tissue lengthening.11,24 Circumferential burns may require alternating use of different orthoses to address all scars.16 Precaution. Aggressive motion at this stage is harmful to fragile tissue and results in more scarring.20 To prevent tendon rupture, do not perform IP motion if extensor tendon involvement is known or suspected. In the later phases of recovery, emphasize exercises to achieve full active and passive wrist and hand motion. Include gentle passive exercises for individual joint tightness. Composite wrist and finger flexion or extension exercises may also be needed for scars that cross several joints (commonly seen with dorsal hand burns). Look for the scar to blanch, which indicates it is being effectively stressed.20 Resistive exercises can help with regaining strength and muscle endurance. Stronger muscles are better able to move against tightening scars. Have the client perform resistive exercises in both directions to address scar and tendon adhesions. Use exercises and therapeutic activity to promote strength, dexterity, coordination, and hand function. Continuous passive motion (CPM) has been reported to be an effective adjunct to therapy in the treatment of hand burns for clients who show little active motion because of pain, anxiety, or edema.25 The goal of scar management is to modulate scars as much as possible to achieve a flat, smooth, supple, and cosmetically acceptable scar. Because scar formation is an unavoidable component of wound healing, the best we can hope to accomplish is to minimize scarring by altering its physical and mechanical properties through interventions, such as compression, silicone products, massage, and physical agent modalities. The exact mechanisms by which these interventions work are not well understood, and objective support of their efficacy is less than adequate, but they have produced positive clinical effects.26,27 Compression can be provided through a variety of means, including orthoses, compression wraps, and pressure garments. The processes of hypertrophic scarring and scar contraction begin shortly after injury; therefore early application of pressure is advised (that is, within 2 weeks of wound closure).16,20,28 As a rule of thumb, use interim compression bandages and gloves until the hand is ready to be measured for a custom-fitted pressure garment. Pressure from self-adherent elastic wraps is effective in both edema and scar management, and these wraps can be used over light dressings as needed (Fig. 34-3).16,28 Grade the amount of pressure to make sure it is tolerable. Prefabricated digital sleeves and gloves are an option once the scar is able to tolerate the shear forces created by putting them on, taking them off, and motion while wearing them. Measure for a custom glove only after edema has plateaued, wounds are smaller than a quarter, and the scar is ready to tolerate the heavier pressure and friction custom gloves impose (Fig. 34-4).20 To be most effective, compression devices should be worn continually except during skin hygiene routines and exercise. It may take time for clients to tolerate full-time wear. Silicone products are available in many forms, including sheets and putty. Some silicone gel sheets are self-adherent, whereas others must be held in place. Silicone can be used alone, but is often combined with pressure although the effectiveness of using both together has been mixed.29,30 Some manufacturers make pressure garments with a thin silicone lining, but these may be more difficult for a client to put on and remove because of increased friction from the silicone. The recommended wearing time for silicone is a minimum of 12 to 24 hours a day; close monitoring is required since its occlusive nature may cause maceration.16,20 Precaution. Do not apply silicone over open wounds or fragile skin. Massage, delivered manually or with a vibrator, may be helpful for freeing restrictive fibers, reducing itching, and relieving pain.31,32 Begin with gentle massage of newly healed skin to avoid blister formation and skin breakdown. As tensile strength improves, progress to greater pressure causing scar blanching and massage with circular motions to work the scar in all directions. Lubricate the scar before massage to precondition the tissue. Massage should be performed at least twice a day.16,20 Physical agent modalities (for example, hot packs, paraffin, fluidotherapy, and ultrasound) have been used for burn scars to precondition tissues for exercise and activity.16,20 Heat can reduce pain and improve elasticity of collagen fibers making the scar easier to mobilize. Paraffin combines the benefits of heat and skin lubrication, both of which are useful before motion. Fluidotherapy can also help with desensitization of hypersensitive scars. Dense burn scars are best heated by ultrasound.

Burns

Anatomy

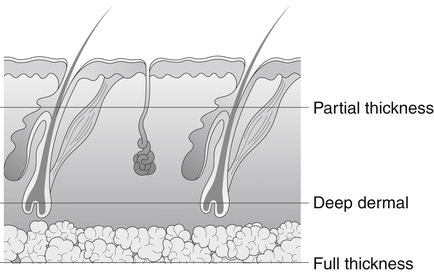

Diagnosis and Pathology

Timelines and Healing

Phases of Burn Recovery

Non-Operative Treatment

Dressings

Positioning

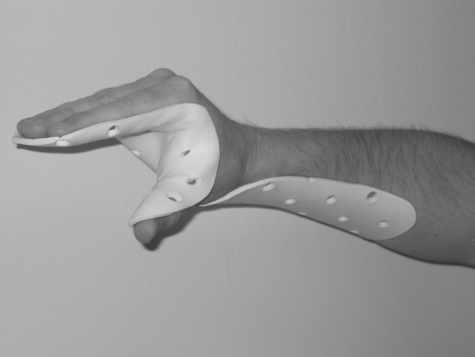

Orthoses

Exercise

Scar Management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine