Chapter 18. Bone and joint infections

Acute osteomyelitis

Bone infection usually involves the bone marrow and is therefore called osteomyelitis. The disease can be acute or chronic.

Acute osteomyelitis is seen in both children and adults. In days past it was a common cause of disease and death but in the last 50 years it has become both less common and less serious.

Pathology

The disease begins with an infection in the juxta-epiphyseal region of the bone. The symptoms often begin after minor trauma, perhaps because the trauma creates a small haematoma from rupture of the very profuse blood vessels near the epiphyseal plate. The haematoma provides an ideal breeding ground for bacteria reaching it from the bloodstream.

Clinical features

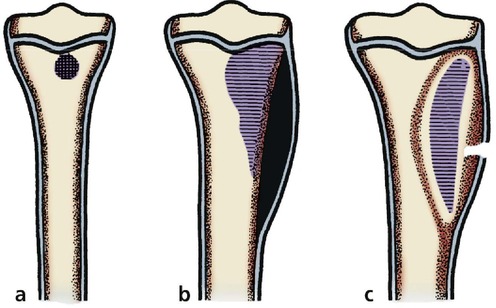

As the infection proceeds, the patient becomes ill and pyrexial and develops excruciating pain because of the tissue tension within the bone. Untreated, the infection spreads until it erodes the surrounding bone and eventually the cortex, allowing pus to strip the periosteum off the bone, and forms a subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 18.1). The pus will eventually discharge through the skin, leaving a bone abscess discharging through a sinus. At this stage the patient has chronic osteomyelitis.

|

| Fig. 18.1 Progress of osteomyelitis: (a) small septic focus next to the epiphyseal plate; (b) collection of pus beneath the periosteum; (c) pus has drained through the skin and an abscess cavity in the bone communicates with skin. |

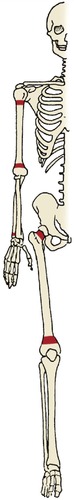

If the epiphyseal plate lies inside a joint the pus will discharge not through skin but into the joint, causing a septic arthritis. The following joints can become infected in this way (Fig. 18.2):

1. Hip.

2. Knee.

3. Shoulder.

4. Elbow.

5. Wrist.

|

| Fig. 18.2 Joints susceptible to septic arthritis. |

Treatment

In the first few days of the disease, when there is a hot tender bone and a pyrexia, the child should be admitted to hospital, the limb elevated and blood sent to the laboratory for haemoglobin, ESR, white cell count and blood culture. Only when the blood culture specimens are safely in the laboratory should antibiotic therapy be given.

The antibiotics given should be the ‘best guess’ based on the prevalent organisms in the hospital and neighbourhood. A good microbiologist will know the most likely organism to cause bone infection in the area, but Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae are the usual culprits. A good antibiotic regimen is a combination of ampicillin 500 mg four times daily and flucloxacillin 500 mg four times daily, although 1 g four times daily may be needed.

If the patient is not clinically better after 2 days treatment and the pyrexia remains unchanged, the affected area of bone should be exposed and drilled to release pus.

Almost every patient with acute osteomyelitis can be cured in this way and chronic osteomyelitis has almost become a disease of the past in developed countries.

Brodie’s abscess. Not all osteomyelitis behaves in this way. The infection can be partly overcome by natural defences and remain confined in an abscess lined by cortical bone. These lesions, called Brodie’s abscesses, are visible radiologically as a small cavity and contain quiescent bacteria.