9. Biopsychosocial approach

Paul Watson

Jim was also 44. He had repeated episodes of low back pain and leg pains over 10 years. A year ago he had a particularly bad episode and suffered loss of sensation and movement in his left foot. He had surgery and a diskectomy. Following surgery he developed a dropped foot and neuropathic pain in his lower leg. He returned to work as a kitchen fitter but 2 months ago experienced another episode of back pain while maneuvring a large cooker. He received extra analgesia from his GP but no advice on exercise or work so Jim started swimming and gentle cycling to help maintain his fitness. His last scan demonstrated degenerative changes throughout the lumbar spine with a large disk prolapse centrally at L2–3 and a small one on the right at L3–4. Jim’s main reason for attending clinic was to get advice on returning to work.

Why a biopscyhosocial perspective?

John and Jim both have back pain as the main reason for consulting but their presentation could not be more different. Obviously the clinical assessment cannot explain the differences and imaging does not explain the severity of pain. It might be easy to simply classify Jim as stoical or motivated and John as weak or unmotivated but those pejorative terms are no use clinically and do not help explain why they are so different. For this we must look to explanations other than the biomedical model.

The foundations of a biomedical approach to disease were laid by Virchow in the early 19th century (Virchow 1858). In this model one first examines the body for signs of abnormal pathology, infers the cause of the disease from the observations, applies a treatment and expects the signs of disease to improve. This works well for isolated pathology but it was incorrectly extrapolated from signs of disease to the cause of disability. A biomedical model of disability is predicated on there being a linear relationship between the cause of the illness, the pathology identified, the severity of the symptoms, the degree of functional limitation and the consequent disability. The simple cure was to address the root cause and everything else would improve of its own accord. However, things are not that simple. In everyday life we know of people who seem to be very disabled by relatively moderate illnesses and complaints and those who despite pain and/or physical impairment do not let it interfere with their ability to work or conduct their hobbies. As you meet patients you will no doubt become aware that some seem to “keep going” despite considerable problems whereas other seem defeated by the same condition and become very disabled and dependent on the help of others.

So what is it that makes people with similar conditions and similar levels of disease so different in their physical function and disability? In the most simple of concepts, it is what people understand and believe about their condition, the way they cope with the condition and their own perception of their ability to be able to do things despite their illness/impairment. The relative contribution of examination (clinical testing, MRI), physical findings (muscle strength, range of motion) or even physiologic tests in nonpain conditions (blood gases, cardiac function in cardiorespiratory disease) varies by condition but in most, nonclinical, mainly psychologic and social factors are important or pre-eminent in explaining the level of disability (Main et al 2008).

Unfortunately, over-reliance on a biomedical model of pain results in patients being classified as malingering or exaggerating their symptoms for secondary gain such as access to benefits or to avoid work or unpleasant circumstances. This does our patients a disservice. And it is not just the medical profession who do this. The same may happen if physiotherapists have an overly biomedical or biomechanical model of musculoskeletal pain.

In order to manage people better we must address the biomedical/biomechanical factors and the psychosocial.

A biopsychosocial model of pain disability

It is important to note that this chapter refers to pain-related disability and not to the perception or reporting of pain as a sensation. This in itself is an interesting subject but here I will concentrate on disability resulting from pain.

Some of the most complete research comes from the musculoskeletal field, particularly low back pain. In this area, not only are we able to look at the factors which are most important in determining the degree of disability but longitudinal studies have demonstrated that psychosocial factors can predict the likelihood of disability over a year after onset. One of the reasons why psychosocial influences in musculoskeletal pain are so well researched is that we cannot externally corroborate a person’s pain, we only have their report to go on. The intensity of pain in chronic pain conditions has often been reported to explain relatively little about disability. Studies have demonstrated that pain explains, at best, about 24% of the disability of people attending physiotherapy for back pain (Woby et al 2007); in tertiary care centers like pain management programs, it might explain 8% or less of disability (Turner et al 2000).

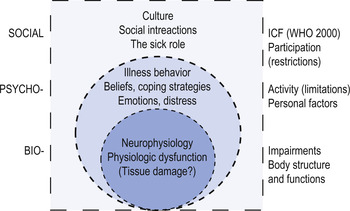

A biopscyhosocial model for pain was developed by Waddell (2004) (see Fig. 9.1); at the core of the model is the perception of a sensation which is nociceptive or interpreted as potentially damaging. We then try to make sense of this sensation. Is it damaging? Do we need to be concerned? Our interpretation/cognitions about the sensation influence our emotional reaction to it; this is the affective component. This interpretation influences what we do about the pain – our pain or illness behavior. If we think it is nothing and it will go away by itself, we generally do little, are unconcerned and carry on. However, we might believe that it is a sign of damage and requires treatment and therefore will consult a healthcare practitioner. All our understanding of health and illness and our reactions to this are influenced by our prior experi-ence, learning and influences from the social environment, e.g. what is acceptable and unacceptable illness behavior for a particular problem (Main et al 2008). Illness behavior is everything we do with regard to a condition, including reporting pain, taking medication, vocalizing, body posture and movement, adopting a sick role and seeking economic benefits (sick pay, social security benefits) (Keefe & Dunsmore 1992).

So what are the important things to consider?

Space prevents a detailed analysis of all the influences on pain-related disability and the interactions here. I recommend you read a good general textbook such as The back pain revolution by Waddell (2004) or Pain management by Main et al (2008). Here I will, of necessity, give just a broad review of the main features.

They can really be put into the following main areas but all of these interlink and overlap and cannot really be seen as completely distinct.

Hypervigilance to somatic sensations is a propensity to notice and focus on a symptom or body part which one is concerned about or which is painful where one perceives a threat (Crombez et al 1999). Our vigilance to sensory events is shaped by the importance (threat value) we give them; the more important we feel they are, the more likely they are to draw our attention. As such, hypervigilance is part of attentional processing.

Increased attention to sensations might be driven by threatening health information, that a particular pain is associated with injury or serious disease, for example. A person who injures their back and who finds certain movements painful is likely to be vigilant of the sensations in their back as they change posture; they may constantly monitor it for changes in sensation. The threat value of the sensation, i.e. an incorrect movement may cause pain, focuses their attention. This makes them more likely to interpret sensations as potentially damaging. Much of the work in this area has been conducted by Crombez and colleagues who demonstrated that chronic pain patients who were hypergivilant to pain not only had a lower threshold for detecting an experimental stimulus, they also had lower pain thresholds (see Van Damme et al 2004 and Crombez et al 2005 for reviews). Hypervigilant patients were also likely to be more disabled.

BELIEFS ABOUT THE CONDITION AND TREATMENTS

The component parts are difficult to separate out. Beliefs are pre-existing views of an illness or condition shaped by our previous experience, social and cultural history (Main et al 2008). If you believe that back pain is a sign of a serious condition which must be rested then you are more likely to rest as a way of managing it. If you believe that back pain requires a MRI scan, you are more likely to demand one and less likely to engage in physiotherapy unless you have had one. In short, beliefs drive behavior.

Expectancies are our beliefs about the future course of a condition – that it will progress or it will be time limited, it will result in increased disability or in only temporary restriction. Our interpretation will influence our behavior as we try and manage the expected future. Expectancies also color our perception of our own role in managing our condition. A patient might expect that it is the physiotherapist’s job to fix them, for example, and not their own.

Outcome expectancies are the perception of the likely outcome of the condition irrespective of the patient’s view of their own ability to influence the future. For example, a patient might have the impression that they have a progressive degenerative disease of the intervertebral disks which will need spinal fusion in the future. This rather bleak picture is unlikely to spur many people into exercise and self-management if they believe the outcome is inevitable and beyond their influence.

Self-efficacy is the belief that a person has the skill or ability to do something (behavior) in order to produce a desired outcome (Bandura 1977), and that the behavior will actually result in a desired outcome. For example, a person with back pain might believe that they are able to control their pain by regulating their activities (pacing) and that this will lead to increased activity without an increase in pain (Asghari & Nicholas 2001). Of course, the opposite can apply: a patient might think that he cannot exercise and exercise will not lead to an improvement; in fact, he might believe increased exercise might lead to a worsening of his condition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree