Chapter 102 Bicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Partial knee arthroplasty developed in the 1950s with devices such as the McKeever and MacIntosh implants.8,16,17,19 Unicondylar arthroplasty (UKA)† and patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) prostheses1,5,6 were used in the late 1970s and publications showed acceptable results at midterm follow-up. Some surgeons combined UKA and PFA when the pathology presented itself at the time of the surgical procedure. The results were once again acceptable at midterm follow-up and had the advantage of ligament preservation and improved proprioception. However, long-term follow-up showed a high revision rate.2 As the total knee arthroplasty (TKA) designs improved, there was less interest in partial knee arthroplasty until Repicci and Eberle21 Romanowski and Repicci24 offered a smaller incision for UKA. Limited incisions for knee arthroplasty became more popular and partial knee arthroplasty became more common.7,9

The bicompartmental replacements from the early 1970s had some recognized advantages over TKA, including improved proprioception, easier range of motion, and faster recovery. However, the two separate implants removed a considerable amount of bone and the operative procedure was complex. Attempts were then made to combine the femoral resurfacing into one single component and there are presently two designs available. Rolston and colleagues22,23 modified a previously existing TKA femoral component and combined this with a UKA-type tibial resurfacing (Journey-Deuce, Smith & Nephew, Memphis, Tenn). The prosthesis removes less bone and spares all the ligaments of the knee. A similar design is also available that makes cutting blocks based on preoperative computed tomography (CT) imaging of the involved knee. The blocks fit anatomically on the native femur and allow shaping of the surface for the implant (iDuo, Conformis, Burlington, Mass). The tibia is cut with more traditional instrumentation. These newer prosthetic designs borrow technology that has been developed for UKA and TKA. This chapter will review the status of the combined procedures and present the surgical technique for the single-piece femoral component.

Historical Perspective

Partial arthroplasty of the knee started with the work of Marmor18 in the early 1980s. The UKA that he designed replaced the medial aspect of the knee without interfering with the other two compartments. The early results were acceptable after some problems with the manufacturing were overcome; however, the approach did not become popular among surgeons in the United States because of the increasing interest in TKA. Berger and associates3,4 and Kozinn and Scott12 maintained interest in UKA and developed newer designs in the late 1980s that began to show more promise for the technique. Long-term results are now available, which indicate that the prostheses mimic the results of current TKA for the first 10 years after surgery and may even be similar in the second decade.

PFA also dates back to the early 1980s, when attempts were made to resurface just the patellar side of the articulation in the belief that the patella was the more involved surface. A metallic implant was used, with only moderate success.11 The implants were modified to include a metal trochlear surface and a polyethylene patella. The early designs did not include many sizes and the prostheses were not anatomically correct.1 Krajca-Radcliffe and Coker13 reported on 30 of 60 knees, with 2- to 18-year follow-up. The results were excellent or good in 84% of the cases. The anatomy was subsequently readdressed and, with modification of the implants, the more recent results are much improved but still do not come up to the level of the TKA.15

In the late 1980s, European surgeons who were performing partial knee arthroplasties looked at the other areas of the knee during surgery and sought to combine partial implants without moving to a total replacement. Argenson and coworkers1 operated on 181 knees for primary patellofemoral disease and added a medial replacement in 57%. The early results were encouraging and similar to those of TKA in the first few years; however, there was a 30% revision rate into the second decade.2 It was concluded that the results may have been compromised by limited early instrumentation and the combination of implants that were not entirely compatible. Cartier and colleagues5 performed 87 PFAs and included a medial UKA in 36 knees (41%). They reported 86% excellent or good results with 2 to 12 years of follow-up.

Lonner14 has continued to pursue bicompartmental replacement using two separate implants that are now more anatomically correct. Early results are encouraging but there is no long-term follow-up.

Rolston and coworkers22 designed a single-piece femoral component that combined the femoral trochlear groove with the medial femoral condyle replacement. This articulated with a unicondylar type of tibial plateau insert and with an all-polyethylene patellar component. The instruments were designed to accommodate the complex nature of the femoral component; the tibial resection guide was a more traditional extramedullary instrument.

Surgical Technique

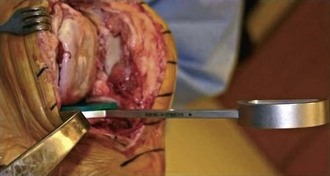

The single-piece femoral components were developed in an attempt to simplify the surgical technique and make the operation similar to a TKA. The procedure can be performed through a limited, minimally invasive surgical approach if the surgeon is comfortable with the option (Fig. 102-1). Otherwise, a standard arthrotomy is acceptable. The tibial resection is performed using an extramedullary guide that is first set for the varus and valgus alignment with reference to the tibial shaft (Fig. 102-2). The depth is set at 2 mm below the deepest point on the medial articular surface. The sagittal alignment, or slope, should be between 5 and 7 degrees and is best if it is set to copy the preexisting tibial slope. Occasionally, a tibia will have a slope that is in excess of 10 degrees, especially in a patient of Eastern descent. It is best not to increase the slope above 10 degrees. If this angle is decreased, the flexion gap will be tightened and some adjustment will need to be made to match the extension gap.

The tibial resection is completed using a power saw for the vertical and horizontal cuts. A pin can be inserted through the cutting guide that protects the remaining tibial surface from any undercutting. After the cut is completed, a spacer is placed into the knee in 90 degrees of flexion and in full extension (Fig. 102-3). The two gaps should be equal at this point. The most common presentation will be a flexion gap that is smaller than the extension gap because of a preexisting flexion contracture. This can be corrected by resecting more bone from the distal femur at the time of the distal resection. If the flexion gap is bigger than the extension gap, the slope of the tibial cut is usually too great and the slope should be decreased by removing bone from the anterior aspect of the tibial cut using the guide with a change in the slope.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree