Benign Vascular Tumors

Hemangiomas of bone are of minor importance when considering lesions that require surgical procedures for diagnosis or therapy. The alterations commonly interpreted as hemangiomas of vertebrae by the radiologist are nearly always asymptomatic and are probably zones of telangiectasis rather than true hemangiomas. Most bona fide hemangiomas in bone are solitary lesions. However, hemangiomas may affect two or more bones of a single extremity, sometimes also involving the overlying soft tissues and occasionally producing serious malformation and dysfunction. Diffuse skeletal hemangiomatosis is a rare disorder in which the lesions most commonly are in the spine, ribs, pelvis, skull, and shoulder. When such hemangiomatosis affects visceral organs as well as bones, the prognosis is poor; otherwise, the osseous process tends to become stabilized, with variable degrees of lytic and sclerotic change.

Disappearing or phantom bone disease, also called massive osteolysis or Gorham disease, may be a form of hemangioma of bone. This relatively rare condition, which usually occurs in children or young adults, is characterized by the dissolution, wholly or partly, of one or several adjacent bones. The affected bones may have a cavernous angioma-like permeation as a prominent pathologic feature. The process is self-limited, but the extent of the progression is unpredictable.

Hemangioendothelioma, or hemangiosarcoma of bone, encompasses a somewhat controversial group of tumors that vary from debatably malignant capillary and cavernous proliferations to highly lethal endothelial sarcomas that sometimes are of multicentric origin. Hemangiopericytoma, another poorly understood neoplasm with poorly defined histologic delineation, is a very rare primary lesion of bone. Malignant vascular neoplasms of bone are discussed in another chapter.

Lymphatic vascular proliferations also produce solitary or multiple zones of rarefaction of the skeleton. When blood escapes from the spaces of a hemangioma, the spaces resemble those of lymphangioma; conversely, if blood is introduced into lymphatic spaces, the features resemble those of hemangioma. Perhaps both types of vascular malformations coexist in some cases.

Glomus tumor may erode bone or even arise within it.

The foregoing suggests the wide range of the clinical and pathologic spectrum of vascular proliferations in bone. A well-defined and lucid classification of these disorders is not available. Accordingly, portions of the following brief description are general.

The bibliography indicates a wide spectrum of vascular disorders affecting bone.

INCIDENCE

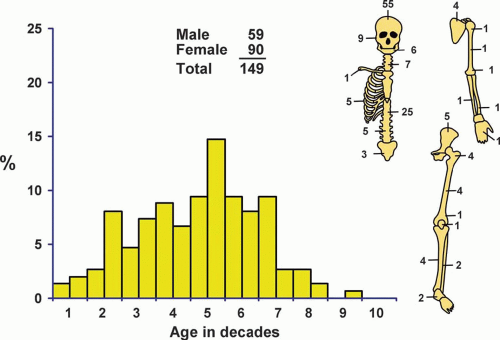

The 149 hemangiomas comprised less than 1.5% of the total series (Fig. 22.1). In addition, there were 21 examples of massive osteolysis. The 109 angiosarcomas and 15 hemangiopericytomas are discussed in Chapter 23.

SEX

Females predominated in a ratio of 3:2.

AGE

According to most reports, hemangiomas are usually found in adults. In the Mayo Clinic series, about 24% of the patients were in the fifth decade of life. The youngest patient was 2 years old and the oldest was 85 years.

LOCALIZATION

Approximately half of the hemangiomas were in the cranium or vertebrae. Fifteen affected the jawbones. Sixteen patients (eight males and eight females ranging in age from 6 to 66 years) had multiple hemangiomas. In five of these patients, multiple skeletal sites were involved. The rest had multiple hemangiomas involving one bone or multiple bones in one topographic site, such as the spine or the ribs. One patient had features suggestive of oncogenic osteomalacia. The distinction between multiple skeletal hemangiomas and massive osteolysis can be difficult and sometimes arbitrary.

SYMPTOMS

Many of the hemangiomas of the skeleton in the Mayo Clinic series were asymptomatic and discovered during a radiographic study for other reasons. Hemangiomas that expand the bone and produce new bone may cause notable swelling. Local pain is sometimes a feature. There may be fractures, including compression fractures of vertebrae. Rarely, spinal cord compression may result. Severe hemorrhage may be encountered during surgical procedures, especially those involving the jawbones. Patients with massive osteolysis have pain and disability commensurate with the degree of osseous involvement.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Physical examination usually does not contribute any specific information. Occasionally, soft tissue or cutaneous hemangiomas provide evidence indicating the nature of the osseous disease. However, such nonosseous hemangiomas are also part of Maffucci syndrome, which includes skeletal chondromatosis.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

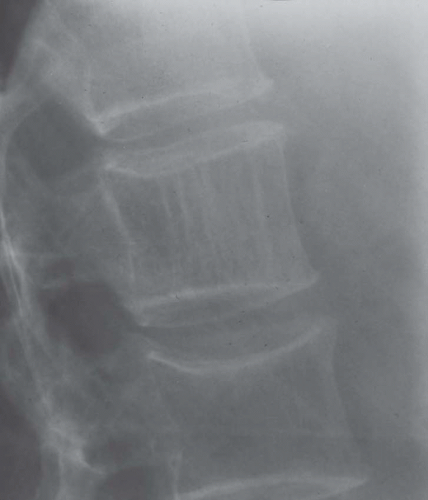

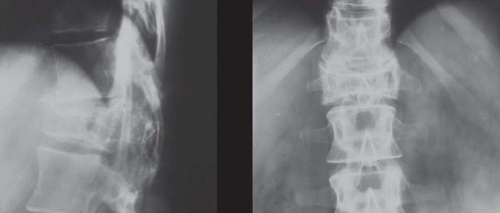

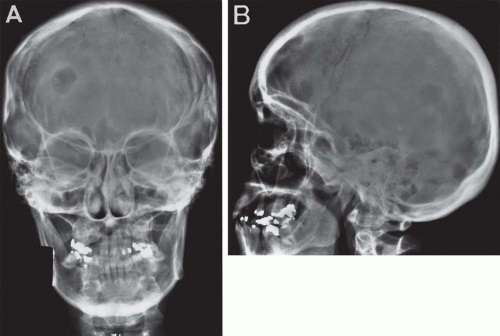

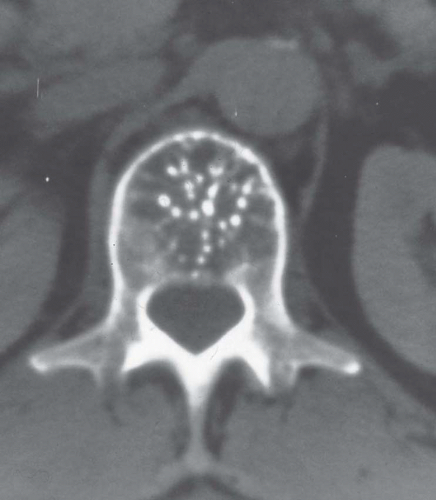

Hemangiomas in vertebrae characteristically cause rarefaction, with exaggerated vertical striation or a coarse honeycombed appearance. These changes produce a characteristic polka-dot appearance on computed tomograms. Ross and coauthors described the magnetic resonance imaging features of vertebral hemangiomas. Unlike most neoplasms of bone, hemangiomas of the vertebrae showed increased signal in both T1- and T2-weighted images. The extraosseous component was not enhanced on T1-weighted images. The authors attributed these signal characteristics to the presence of fat in the intraosseous component of vertebral hemangiomas. In the skull, hemangiomas produce a well-circumscribed zone of rarefaction that

may have a honeycombed appearance and is often associated with outward expansion of the bony profile. This expanded zone may show striations of bone radiating outward from the center of the lesion, giving rise to a sunburst appearance. In other bones, hemangiomas produce rarefactions that may have features like those described above. In most long bones, however, the appearance is nonspecific. When a hemangioma occurs in soft tissue, the lesion may contain phleboliths (Figs. 22.2, 22.3, 22.4, 22.5, 22.6, 22.7 and 22.8).

may have a honeycombed appearance and is often associated with outward expansion of the bony profile. This expanded zone may show striations of bone radiating outward from the center of the lesion, giving rise to a sunburst appearance. In other bones, hemangiomas produce rarefactions that may have features like those described above. In most long bones, however, the appearance is nonspecific. When a hemangioma occurs in soft tissue, the lesion may contain phleboliths (Figs. 22.2, 22.3, 22.4, 22.5, 22.6, 22.7 and 22.8).

Figure 22.3. Computed tomogram of a vertebral hemangioma. In cross section, bony trabeculae produce a polka-dot appearance. |

Figure 22.4. Hemangioma of the vertebral body has destroyed the vertebra and extended into soft tissue. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree