CHAPTER 2 Becoming a Shoulder Arthroplasty Surgeon

Shoulder arthroplasty is much less frequently performed than hip and knee arthroplasty and accounts for only 3.1% of inpatient joint replacements in the United States,1 largely because hip and knee arthrosis is much more common than glenohumeral arthrosis. Additionally, patients with glenohumeral arthrosis tolerate the symptoms better than those with hip and knee arthrosis because they do not rely on their shoulders for locomotion. Consequently, a busy general orthopedic surgeon may easily perform more than 100 hip and knee replacements in a given year and yet see fewer than five patients who are candidates for shoulder replacement during that same period. Moreover, most orthopedic residencies offer the same lower extremity–focused arthroplasty experience. This has been confirmed by our shoulder fellows, most of whom have seen fewer than five total shoulder arthroplasties during a 4-year orthopedic residency.

The desire and necessity to perform shoulder arthroplasty have evolved from advances made in the field of shoulder surgery during the last 2 decades. Shoulder arthroscopy has developed from a solely diagnostic procedure to a part of the surgical armamentarium that allows treatment of nearly every shoulder problem formerly treated by open surgery. As a result, many orthopedists, largely through technique-driven courses, have become proficient at arthroscopic shoulder procedures, including but not limited to rotator cuff and labral repair. As these same surgeons develop a practice in which an increasing number of patients with shoulder problems are treated, it becomes inevitable that they will encounter diagnoses not amenable to arthroscopic treatment, specifically, diagnoses best treated by shoulder arthroplasty. An aging population that is living longer and remaining more active has contributed to the increasing number of shoulder arthroplasties performed annually as well. In the United States alone, 28,742 shoulder arthroplasties were performed in 2003, a 14.4% increase over the previous year.1 This chapter reviews some basic concepts that must be understood when an orthopedic surgeon decides to become a shoulder arthroplasty surgeon.

ANATOMY

Cutaneous

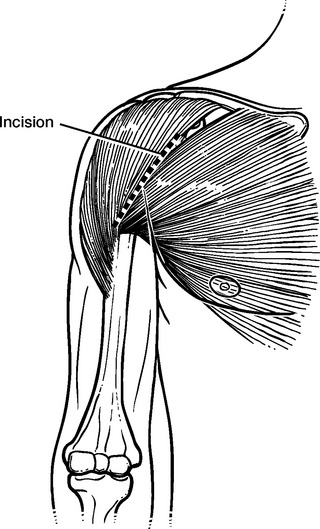

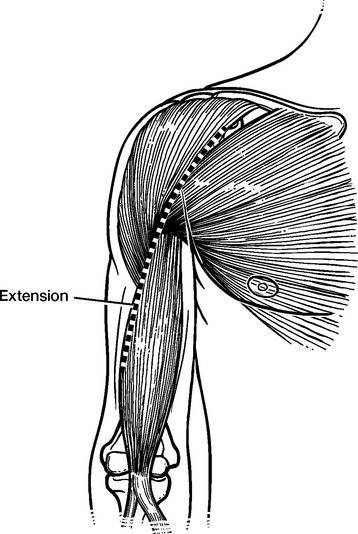

The palpable coracoid process marks the proximal extent of the skin incision for the deltopectoral approach. In thin patients, the deltopectoral interval may be palpable to better assist in directing the skin incision (Fig. 2-1). In revision cases, the skin incision may be extended distally along the lateral aspect of the biceps brachii muscle, which is also palpable (Fig. 2-2).

Subcutaneous

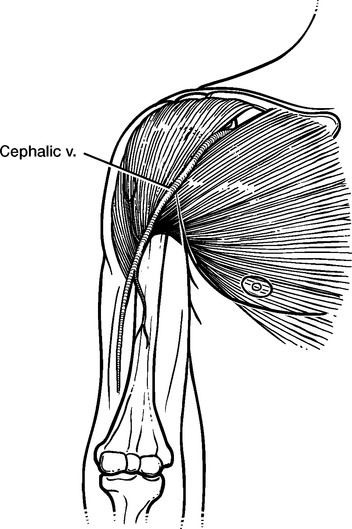

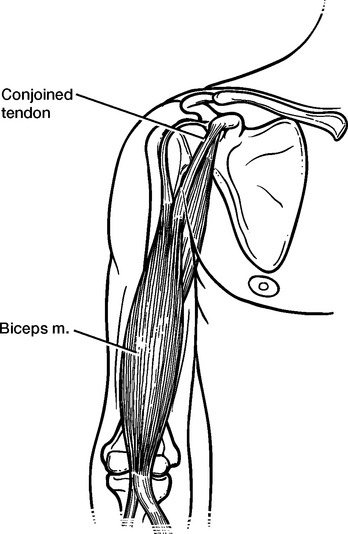

The deltopectoral interval is marked by the cephalic vein. This vein has many small branches, most of which enter the deltoid muscle (Fig. 2-3). The deltoid has attachments at the acromion and the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. The pectoralis major has attachments at the clavicle, the sternum, and the humerus just lateral to the long head of the biceps brachii tendon (Fig. 2-4).

Coracoid/Conjoined Tendon

Immediately deep to the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles is the conjoined tendon of the coracobrachialis and the short head of the biceps brachii (Fig. 2-5). This structure passes from the tip of the coracoid process (the proximal extent of dissection) to the anterior humeral shaft. The coracoid process also serves as the point of attachment of the coracoacromial ligament laterally and the pectoralis minor tendon medially (Fig. 2-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree