syncope (66%). Cardiac anomalies appear to account for the rest.9 Sudden death due to cardiac causes is most often attributed to HCM; as much as 50% of cardiovascular SCDs may be attributable to HCM.15,17 HCM is followed by coronary artery anomalies, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), myocarditis, Marfan syndrome, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in order of prevalence.4,6,17 Latent coronary artery disease (CAD) dominates the incidence of SCD after the age of 35 with vast majority of causes (80%).17 Table 3.2 lists the causes of SCD based on order of frequency.

TABLE 3.1 AHA Consensus Panel Recommendations for Preparticipation Athletic Screening4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 3.2 Causes of Sudden Death in 387 Young Athletes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

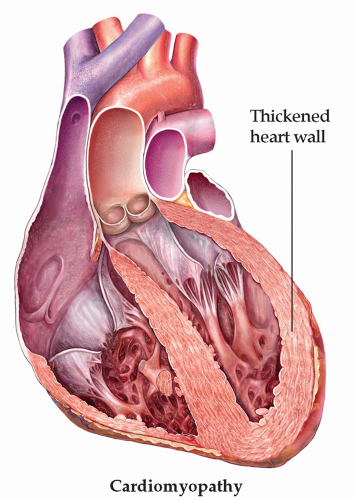

atrial and ventricular cavity size enlargement, without systolic or diastolic dysfunction, is also present because of increased blood volume. This is defined as the athlete’s heart. These changes may occur within weeks of beginning a training program, are probably proportional to the intensity and duration of training, and resolve with decreasing exercise loads.18 Electrocardiogram (ECG) findings in athletes can mimic cardiac injury patterns and may lead to unnecessary exclusion from participation.4 Conversely, adolescent athletes rarely exhibit deep T-wave inversions;19 2% of athletes exhibit increased left ventricular (LV) wall thickness of 13 to 15 mm, thus overlapping the diagnostic criteria for HCM; and 15% of athletes have LV chamber size greater than 60 mm, which can raise concern for cardiomyopathy despite normal LV function.20 Referral for further diagnostic testing is warranted, including echocardiogram (ECHO) (Fig. 3.1). Careful consideration should be given to athletes in this gray zone, as the risk for SCD is considerable, yet overly strict guidelines may exclude many athletes not otherwise at risk. ECG findings in athletes may return to normal, but ECHO findings continue to display HCM in those athletes with the disease.21 Adolescent athletes rarely exhibit chamber size greater than 12 mm; LV wall thickness greater than 12 mm should prompt further evaluation for HCM.22 Athletes with LV wall thickness greater than 15 mm on ECHO should be referred to a cardiologist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree