Athlete with Rash

Christopher J. Lutrzykowski

INTRODUCTION

There are a multitude of exanthems that affect the athlete. The number and breadth of rashes mimic the general population, and the primary care provider must have a sound foundation in diagnosing and treating those conditions. There are eruptions, however, that bear specific emphasis for the provider caring for athletes due to their morbidity and communicability. The presence of certain rashes may also exclude the athlete from sports participation unless properly covered and/or treated. This chapter will focus on four types of skin infections commonly found in athletes that can affect their participation: tinea, herpes, cellulitis/furunculosis, and molluscum contagiosum. Special attention will be addressed to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (cMRSA) due to the recent rise in incidence and significant deleterious effects on athletes.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

For a variety of reasons, athletes are at risk for particular skin disorders. The athletes’ dermis is under constant stress due to their sport exposure as well as microenvironmental conditions (moisture, heat) and unique macroenvironmental conditions (heat, cold, water, sun). Additionally, the dermis can be affected by systemic stress from exercise, including decreased immunity and alterations in blood supply. The normal skin barrier can be easily compromised with close skin contact, abrasions, and cuts. Furthermore, the metabolic stress of exercise may compromise an athlete’s short-term immunity and increase their risk of skin infections. Team sports also present a risk for athletes in that they are often sharing space and personal items among themselves.1, 2, 3

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There are no formal data on the incidence or prevalence of skin disorders or exanthems in athletes as outbreaks can occur sometimes in sporadic fashion. Prevalence can also vary by geography and patient population.

NARROWING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

History

It is paramount to obtain an adequate history when an athlete presents with a rash. In addition to location, noting the time of onset and precipitating factors is important in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Pertinent questions include the following: Was there a prodromal symptom complex? Was there fever? Did any other team member present with a rash? Was the rash in a shaved area? Is the rash painful, itchy, and raised? Were any new creams, detergents, or topical ointments used? Is there any comorbid medical illness? A good history will help the clinician to a narrower differential diagnosis and streamlined care.

Evidence-based Physical Examination

With clues taken from a thorough history, the physical examination guides the clinician to an appropriate diagnosis and treatment. The athlete may present with multiple types of rash, and careful skin examination is important. Rashes cannot be adequately diagnosed through clothing; thus, adequate visualization is important. Is the rash macular or papular? Is it red? Where is it located? Are there satellite lesions? Is it vesicular? Is there a scale? Are there lesions in various states of healing? Are there areas of central clearing? Does the rash vary in size and shape? These questions among many also may help the clinician arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory

Lab testing may be appropriate for specific diseases, including serologies. While not explicitly listed below, Lyme titers are helpful in the diagnosis of Lyme disease, in particular if IgM levels are elevated.

Imaging

Imaging is rarely useful in the diagnosis of rash. It may prove beneficial in the presence of a cellulitis if osteomyelitis is a considered diagnosis.

Other Testing

Skin scrapings, shavings, and biopsy can prove useful in the diagnosis and treatment of rashes, in particular in recalcitrant cases. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (see later in the chapter) may prove a useful adjunct as well. Wound cultures are always recommended when accessible or clinically indicated. This is particularly true with the rise of cMRSA.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH TINEA

Tinea refers to dermatophyte infections that predominantly stem from three different genera. Risk factors for tinea include direct contact with soil, infected humans and animals, and fomites.3 Dermatophytes invade and proliferate in keratinized tissue, including skin, hair, and nails.3 Tinea clinically are subdivided and named based on location. Several locations have been described and include tinea capitis, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis. Each will be discussed separately.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH TINEA CAPITIS

No incidence data are available for tinea capitis among athletes, but it can occur in epidemic form.4,5 Athletes may present with alopecia, desiring treatment.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

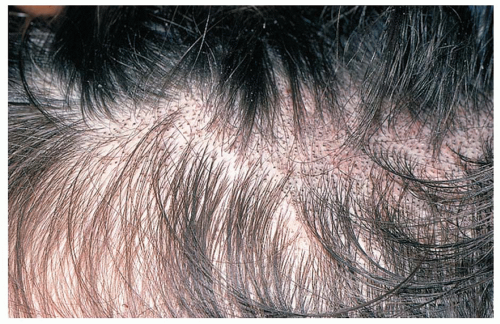

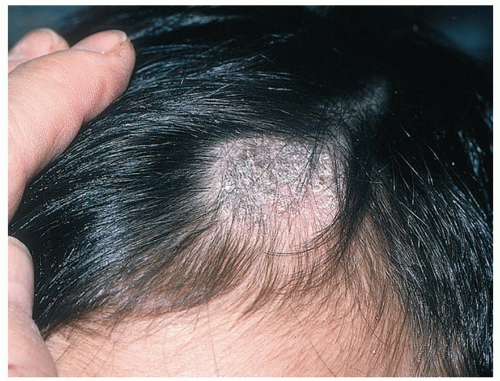

Multiple clinical presentations exist for tinea infections of the scalp. Black dot type is named after the fractured hair follicles from tinea infection (Fig. 6.1). Gray patch type, which is most common, is noted for circular areas of alopecia (Fig. 6.2). A kerion may be present, which is a slightly erythematous boggy mass with alopecia that may progress to scarring (Fig. 6.3).

FIG. 6.1. Tinea capitis: black dot type. Reprinted with permission from Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. |

FIG. 6.2. Tinea capitis: gray patch type. Reprinted with permission from Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. |

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Skin scrapings may be isolated on a slide for microscopic examination with 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH). Tinea have characteristic hyphae with septate branching and when present can confirm the diagnosis. Scrapings and hair may also be sent for fungal culture.

TREATMENT

General Measures

Tinea may be spread by fomites, and cleansing mats, headgear, and clothing may decrease spread among other athletes.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Topical therapy alone with selenium sulfide and ketoconazole shampoos is often not enough to clear infection but may be used as an adjunct to oral therapy.

Mainstay of treatment is oral therapy with griseofulvin, itraconazole, or terbinafine.3

Treatment must continue until clinically and microscopically clear.3

Prognosis/Return to Play

Overall prognosis is excellent, but recurrence rates are high in affected individuals. For return-to-play guidelines in athletes with close skin contact, see the “Approach to the Athlete with Tinea Corporis (Gladiatorum)” section.

Complications/Indications for Referral

Scar and alopecia may be permanent. Referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases and treatment failures.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH TINEA CORPORIS

Tinea corporis is a common skin dermatophyte seen in all age groups. Tinea corporis, common among wrestlers, is also known as tinea gladiatorum and is discussed in greater detail in the following sections.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

This dermatophyte infection starts clinically as a round, erythematous plaque that expands radially with eventual central clearing (Fig. 6.4). The infection may be an isolated lesion or multiple lesions involving a variety of skin surfaces. Tinea corporis may have an atypical presentation with vesicles, pustules, or crusts.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Skin scraping, shaving, or biopsy may be necessary to diagnose the rash.

TREATMENT

General Measures

As listed in the “Approach to the Athlete with Tinea Corporis (Gladiatorum)” section.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Treatment is topical in isolated cases, but oral therapy is necessary for disseminated cases.3 See later in the chapter for tinea corporis gladiatorum.

Prognosis/Return to Play

Overall prognosis is excellent, but recurrence rates are high in affected individuals. For return-to-play guidelines in athletes with close skin contact, see the “Approach to the Athlete with Tinea Corporis (Gladiatorum)” section.

Complications/Indications for Referral

Referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases and treatment failures.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH TINEA CRURIS

This is very common among athletes of all sports and ages. Absolute incidence data are lacking.

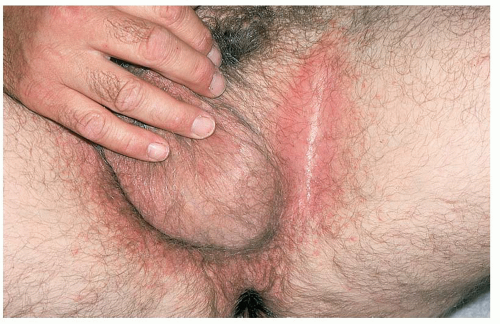

FIG. 6.5. Tinea cruris. Reprinted with permission from Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. |

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Tinea cruris typically presents as a red, variably pruritic rash with a raised scaly border (Fig. 6.5). It spares the scrotum, which helps distinguish this rash from other entities such as Candida sp.3 and erythrasma. Risk factors for the development of tinea cruris include sweating, warm moist environment, tinea pedis, and toenail onychomycosis.3

TREATMENT

General Measures

Tinea cruris advances in warm moist environments; thus, prevention strategies include drying the groin with a separate towel than used for the feet, putting on socks before undergarments, and treating other areas (tinea pedis) infected with dermatophytes.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Treatment is usually topical, but oral systemic therapy may be needed for severe or recalcitrant cases.

Prognosis/Return to Play

Overall prognosis is excellent, but recurrence rates are high in affected individuals. No specific return-to-play guidelines are available, but for athletes with close skin contact, one may want to refer to the guidelines listed under the “Approach to the Athlete with Tinea Corporis (Gladiatorum)” section.

Complications/Indications for Referral

Referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases and treatment failures.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH TINEA PEDIS

As with other tinea infections, this common rash presents in all ages and sports.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Tinea pedis is a dermatophyte infection of the feet that presents in various forms. The most common presentation is in the web spaces between the toes (Fig. 6.6). The skin appears macerated, scaly, and cracked, and the rash tends to be intensely pruritic. Bacterial superinfection causes the classic “athlete’s foot.”3 The infection can also present in a “moccasin” distribution as well as a pustular pruritic form.

TREATMENT

General Measures

Adjunctive agents to decrease sweating and antifungal powders may be useful.

Frequent sock changes and a dry environment may also prove useful for clearing the infection.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Topical agents are effective but may need to be used for up to 4 weeks to achieve eradication.3

FIG. 6.6. Tinea pedis. Reprinted with permission from Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. |

Prognosis/Return to Play

Overall prognosis is excellent, but recurrence rates are high in affected individuals. No specific return-to-play guidelines are available, but for athletes with close skin contact, one may want to refer to the guidelines listed under the “Approach to the Athlete with Tinea Corporis (Gladiatorum)” section.

Complications/Indications for Referral

Referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases and treatment failures.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH TINEA VERSICOLOR

Tinea versicolor is caused by organisms different from those that cause other tinea infections. Etiologic species include Pityrosporum orbiculare and Pityrosporum ovale. The incidence of this rash is unknown among the athletic population.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The lesions can present as either hyper- or hypopigmented macules on the trunk and upper extremities and may be pruritic (Fig. 6.7). Lesions begin as multiple small, circular macules of white, pink, or brown color that enlarge radially.13 These may present in various forms and may be nearly indistinguishable in white athletes in the winter. In black athletes the lesions may appear hyperpigmented. The lesions are most common on the upper trunk but may appear on any skin surface.13

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The dermatophyte can be obtained from skin scrapings and identified under microscopy with the characteristic “spaghetti and meatballs” appearance of budding yeast and branched hyphae.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree