CHAPTER 18 Assessment of the at-risk foot

Introduction

Life expectancy is increasing steadily throughout the Western world as a result of improvements in public health, advances achieved by the pharmaceutical industry and advances in health technologies. However, this good news is tempered by the fact that as a result of modern lifestyles, new public health challenges have emerged. The new epidemics are cancer, diabetes, chronic heart disease, mental distress and illness (Hewitt 2006). The World Health Organization has estimated that if we could eliminate the major risk factors of smoking, obesity and physical inactivity, the great majority of heart disease, strokes and type 2 diabetes would be prevented. The prevalence of diabetes in the UK is estimated to be around 2.5 million adults today and is expected to rise to around 3 million by the year 2010 (Diabetes UK 2004). The International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, which provides data for 215 countries, estimates that in 2007 approximately 246 million people had diabetes worldwide. The worldwide estimate is expected to rise to 380 million by 2025.

For disability, which is a major concern for later life, research has shown that while the level of severity of disability has diminished overall, the additional years of life gained are not free from disability. Chronic diseases that affect the ageing population include disorders of the musculoskeletal system such as the inflammatory arthropathies (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis and gout). According to Michelson et al (1994) foot pain has been reported in up to 94% of people suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. With due consideration of the health problems now and in the future, it is timely to focus on the concept of the ‘at-risk’ foot and the associated complications. The aim of this chapter is to inform the lower-limb practitioner in the identification, assessment and evaluation of the patient at risk of the pedal complications of ulceration, structural deformity, infection and gangrene.

Normal homeostasis of the lower limb is dependent on structurally sound and physiologically normal function of hormonal, circulatory, neurological, musculoskeletal and dermatological systems. Tissue vitality may be affected by any disruption of these systems and is most reliant on the integrity and physiology of the skin. Maintenance of tissue viability of the skin is vital to prevent the unwanted aforementioned adverse events that result from a break in the integrity of the skin. The key protective functions of the complex organ that is the skin are covered in detail in Chapter 8.

The at-risk foot

The term ‘at-risk foot’ is used to describe the foot that is at risk of ulceration and loss of tissue viability. Many risk factors have been identified and it is the combination of intrinsic risk factors together with extrinsic factors in the form of mechanical stress that leads to a break in the continuity of epithelial tissue and subsequent complications. The associated morbidity and mortality is significant, particularly in those affected with diabetes mellitus and the prognosis for many is poor (Laing et al 2003). The threat of amputation looms over many of the at-risk group with resultant reduction in mobility, poor quality of life and decrease in life expectancy (Frykberg et al 2007). It has been estimated that every 30 seconds, worldwide, a lower limb or part of a lower limb is amputated as a consequence of diabetes.

The role of the healthcare practitioner when managing the patient ‘at risk’ includes:

• adopting a holistic, biopsychosocial approach to assessment

• appropriately assessing and evaluating risk factors

• developing effective preventive and education strategies

• appropriately negotiating care planning and risk factor management

• recording and charting assessment findings

• developing an integrated care pathways and acting on them

• appropriate and timely referrals when dealing with emergency situations

Trauma

Skin and the underlying soft tissues have a great capacity to withstand the mechanical stresses from everyday activities and the integral strength and elastomeric properties of skin is provided by the unique properties of collagen and elastin (Tzaphlidou 2004). However, depending on the degree of sustained trauma to the skin, the body’s response to inflammation will initiate the repair process in a complex series of biochemical events (Williamson & Harding 2000).

Trauma may occur in many forms including burns, lacerations, incisions and compression injuries. More minor trauma that occurs more frequently include friction, shear, pressure and ultraviolet radiation. In the healthy individual, the minor stresses will be attenuated or dissipated with no noticeable damage to the tissues. In the ‘at-risk’ population, these minor stresses may result in a cascade of events that leads to significant tissue loss. Once the skin has been breached, the potential for infection is enhanced in those who are susceptible and healing will be delayed. It is important at this point to emphasise the requirement to identify the source of extrinsic trauma that leads to the development of ulceration and infection. This provides important information to evaluate the wound and to adopt preventive strategies. For example, with the neuroischaemic diabetic foot, which is at great risk of ulceration, there is usually a source of extrinsic pressure that initiates a breakdown in the skin with subsequent ulceration. It is important for the practitioner to appreciate the fact that through the minor trauma of ill-fitting footwear, a limb may require amputation and a life may be threatened as a consequence (Adler et al 1999).

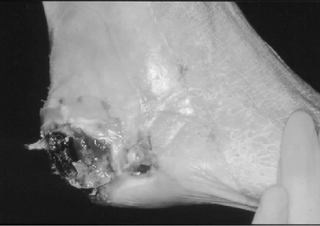

Assessing the extrinsic factors and developing preventive strategies is a key component of management and it is not always possible to eradicate all of the various sources of trauma. One potential source of excessive pressure is, ironically, generated by lying supine in a hospital bed. In a study by Boulton (1996) heel to bed pressures were measured to be between 50 mmHg and 94 mmHg. If this exceeds normal capillary pressure, then as a result of the ischaemia and reperfusion cycle, pressure necrosis can occur (Fig. 18.1 ![]() ) (Tsuji et al 2005).

) (Tsuji et al 2005).

Other reported sources of trauma precipitating foot ulceration include rubbing from footwear and as a consequence of surgery. Macfarlane & Jeffcoate (1997) reported that rubbing from footwear was the most common precipitant (20.6%) in a prospective study of 669 ulcers seen in a multidisciplinary foot clinic. Trips and falls have also been identified as contributors to foot ulceration and the National service framework for older people has stated the aim is to reduce the number of falls which result in serious injury (Department of Health 2001). This initiative may help in the reduction of foot wounds in the at-risk population.

There is a substantial body of evidence that has identified the risks of ulceration in the diabetic population. Whilst there are other at-risk groups, people with diabetes are considered to have the greatest risk of ulceration. Approximately 2–3% of individuals with diabetes develop one or more foot ulcers each year and an estimated 15% will develop a foot ulcer during their lifetime (Frykberg et al 1998). Foot ulceration impacts on the individual’s functional ability and quality of life (Price & Harding 2000). Pecoraro et al (1990) demonstrated that in more than 80% of cases, amputation was preceded by a foot ulcer. The economic burden is high with an estimated £244 million spent in 2001 on foot ulcers and amputations in the UK (Gordois et al 2003).

Risk factors in diabetic foot ulceration

It is important to be able to identify the most significant risk factors that predispose the diabetic person to foot ulceration. Similarly it is imperative to identify and evaluate the risk factors that may affect the prognosis and outcomes of such wounds. This process will aid the healthcare practitioner to develop a care pathway with appropriate referral criteria to other healthcare agencies. Many researchers have identified causal pathways and risk factors for ulceration. Targeting modifiable risk factors can reduce the incidence of foot ulcers or amputations (Malone et al 1989, Uccioli et al 1995).

The risk factors that are most commonly found in the causal pathway to a foot ulcer are:

A pivotal prospective study in a North American Indian population (Rith-Najarian et al 1992) identified risk factors that were predictive for foot ulceration. These included:

• structural foot deformity (hallux valgus or varus, claw and hammer toes, bony prominence or Charcot foot)

In this study, the researchers found that an ulcer was about five times more likely to occur in a patient with a history of disease or lack of sensation than in a patient without these factors. In another prospective study, Boyko et al (2006) followed 1285 diabetic subjects without foot ulcer (mostly male) over 3 years (mean 3.38). Significant predictors of foot ulcers included: impaired vision, prior foot ulcer, prior amputation, monofilament insensitivity, tinea pedis and onychomycosis. Merza & Tesfaye (2003) in a review of risk factors for diabetic foot ulceration describe other identified risk factors (Box 18.1).

Screening

Screening for risk factors for ulceration is recommended by various national and international guidelines (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2001, National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2004) and is an important part of a primary prevention programme. However, it may not be a cost-effective activity if the whole diabetic population has to be screened in order to identify the ‘at-risk’ group of patients. Any screening programme has to be carefully considered and the resources have to be identified. The implications and consequences of screening programmes are far-reaching and will impose a significant burden of the health economy. Identification of risk factors may be important, however, it may be considered even more important that prevention programmes can achieve their aims.

International guidelines suggest that people with diabetes should be examined for potential foot problems at least once a year (Apelqvist et al 2007). The Consensus on the Diabetic Foot suggests a risk categorisation system should be adopted with a recommended check-up frequency (see Table 18.1).

Table 18.1 Risk categorisation system

| Category | Risk profile | Check-up frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | No sensory neuropathy | Once a year |

| 2 | Sensory neuropathy | Once every 6 months |

| 3 | Sensory neuropathy, signs of peripheral arterial disease and/or foot deformities | Once every 3 months |

| 4 | Previous ulcer | Once every 1–3 months |

There is evidence that the identification of the risk category can predict an episode of ulceration (Leese et al 2006). This may help to target resources to the appropriate patient groups. Numerous guidelines have suggested reliable tools to use in the identification of peripheral neuropathy and the presence of arterial disease (Best practice pathway 2007). However, there remains debate about the number of test sites required to ascertain loss of protective sensation. Table 18.2 gives the clinical tests used to identify risk based on best available evidence. In addition, a medical history to assess other risk factors, e.g. history of ulceration, will be required. There are other methods to determine extent of neuropathy, e.g. the Neuropathy Disability Score (Boulton 2005), but for a simple screening tool, the above tests are recommended.

Table 18.2 Simple identification of risk factors

| Sites | |

|---|---|

| DEGREE OF SENSORY NEUROPATHY | |

| Loss of protective sensation (10 g nylon monofilament) | Pressure sites of plantar aspect of the hallux, 1st and 5th metatarsal heads of both feet |

| Loss of vibration perception (128 Hz tuning fork) or vibration perception threshold (neurosthesiometer) | Distal end of hallux and medial and lateral malleolus Same sites above >25 V |

| PERIPHERAL ARTERIAL DISEASE | |

| Absence of two or more pedal pulses | Dorsalis pedis and tibialis posterior pulses |

| Ankle–brachial pressure index | Both dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses |

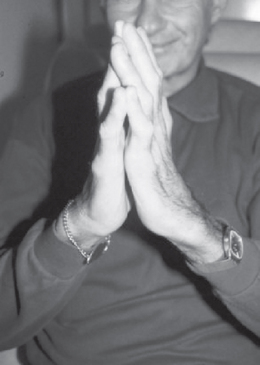

| OBSERVATION OF FOOT DEFORMITY | Hallux abductovalgus, hallux rigidus, pes cavus pes planus and Charcot’s foot deformity |

| Limited joint mobility syndrome | Positive prayer sign (see Fig. 18.2) |

| Observation of plantar callus | Pressure points of hallux, all metatarsophalangeal joints, apices of digits and heels of both feet |

Having a history of a previous ulcer is a significant risk factor for a recurrence (Abbott et al 2002, Boyko et al 1999, Peters et al 2001). In an important publication by Frykberg et al (1998) of the 251 patients studied, 99 patients had a current or prior history of ulceration, and 33 with active ulcers. Recurrence rates have been reported to range from 28% at 12 months (Chantelau et al 1990) to 100% at 40 months (Uccioli et al 1995). Apelqvist et al (1993) reported a recurrence rate of 34% and 70% after 2 and 5 years, respectively. Clearly having had a history of ulceration is the most important risk factor for further ulceration.

Renal failure

Identification of risk factors does not only inform the practitioner who is at risk, but also informs treatment options and likely prognosis. For example the diabetic patient with end-stage renal failure and peripheral arterial disease who presents with a foot ulcer has a high risk of infection and a poor prognosis (Boufi et al 2006).

Established renal failure in diabetes is associated with a high incidence of foot ulcers and gangrene. This problem may be particularly associated with the onset of renal replacement therapy. There is evidence that haemodialysis causes hypoxaemia and this can be reflected in the subsequent decrease in lower limb transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2) (Hinchcliffe et al 2006). These patients are liable to be prescribed immunosuppressant drugs and are therefore at great risk of infection. This patient group will have underlying advanced diabetic microangiopathy and often have concomitant peripheral arterial disease and are hypertensive. Clearly, a holistic assessment of all of the risk factors is needed to evaluate risk factor status for possible future ulceration.

Biopsychosocial approach

Psychosocial factors

Recognition of the importance of both psychological and social factors in the care of people with diabetes is required to assess and facilitate optimum management. Neuropathy, pain, foot ulceration and amputation can have a devastating effect on the person with diabetes. This may lead to social isolation, depression and failure to maintain healthy behaviours. As a consequence there may be a downward spiral of poor health, further complications and early death (Vilekyte et al 2003).

The quality of life can be severely affected by the complications of neuropathy and foot ulceration. The psychosocial assessment of patients suffering from these complications is vital to determine further risk of the complications and improve care. A seminal research study by Vilekyte and colleagues (2003) led to the development of a validated quality-of-life instrument (NeuroQoL) that can reliably capture the key physical and psychosocial effects. Psychosocial factors that are measured include disruption of daily living and interpersonal-emotional burden. Healthcare practitioners should consider the use of this assessment tool to inform any behavioural strategy and evaluate effectiveness of quality of care.

The podiatrist and other healthcare providers have to develop the skills and knowledge in order to embrace a biopsychosocial approach to caring for the at-risk diabetic person (Kinmond et al 2003). Psychological and emotional wellbeing is the foundation on which all other aspects of the treatment regimen rest and failure to consider these aspects in management of the diabetic foot can lead to poor outcomes (Clark 2006).

Motivational interviewing

Hampson and colleagues (1996) have shown that personal models of diabetes, e.g. beliefs about the consequences of having diabetes and the effectiveness of treatment can predict self-care behaviour. It is therefore important to explore with the person with diabetes or other chronic illness about their perceptions of how their illness affects them. This holistic approach to assessment needs to include an exploration of the patient’s perceived susceptibility to their illness and foot complications. It is only by adopting an empathetic approach and willingness on behalf of the patient to disclose such information that valuable insights may be gained to facilitate change in self-management.

Practice point

These are simple tools that practitioners may consider to enhance the assessment process. This patient-centred approach has been recommended (Lincoln et al 2007) and is a key part of the assessment process. In addition many of the at-risk patients may well have depression, which will affect their health behaviours and communication. All practitioners should consider that diabetes doubles the risk of depression (Anderson et al 2000).

Assessment of foot health knowledge and behaviour is often overlooked as part of the assessment process and yet it is often the health behaviours that lead to an episode of ulceration and further recurrence. One new assessment tool that has been validated is the Nottingham Assessment of functional Footcare (NAFF). This questionnaire explores both knowledge and behaviour and could be used to test the effectiveness of education and identify specific areas of poor protective behaviour that individuals may have (Lincoln et al 2007).

Other useful health-related quality of life and diabetic foot ulcer assessments include:

Socioeconomic factors

Many of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity are related to low socioeconomic status. Individuals with low socioeconomic status suffer from more diseases and their consequences than from those who enjoy higher socioeconomic status (Alder et al 1993). Studies have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with obesity, depression and diabetes (Everson et al 2002). The relationship is complex and there is evidence that those with low socioeconomic status have a greater prevalence of smoking, higher alcohol consumption, poorer diets and more sedentary lifestyles. These health behaviours are more likely to put the person at greater risk of developing the chronic disorders stated.

Although it has been acknowledged that poor socioeconomic status is a risk factor for diabetic foot complications (Apelqvist 2000), the evidence is fairly sparse. The at-risk population tend to be older, and there are some difficulties in measuring socioeconomic factors with this group. As an example, social class measured by occupation is not possible with a retired population. The lower-limb practitioner should take into account the socioeconomic status of the patient as this may inform the assessment and prognosis. In addition, the practitioner may be able to refer the patients to other agencies, for example social services, voluntary support for further assistance.

Age

The ageing population in the UK and other developing countries is well acknowledged and statistics from Help Age International suggest there are 550 million older people worldwide, which will increase to 1.2 billion by 2025 (Help Age International 2005). With this demographic background and an expected increase in the prevalence of diabetes, the proportion of at-risk patients will increase substantially. In the context of the at-risk foot, tissue viability may be compromised by the ageing process. The ageing process is a complex process and can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic ageing.

Intrinsic ageing is mostly genetically determined and extrinsic ageing, more commonly referred to as photoaging, is caused by environmental exposure in the form of ultraviolet radiation (Fisher et al 2002). These aging processes have both qualitative and quantitative effects on collagen and elastic fibres in the skin (El-Domyati et al 2002). Although the pathomechanisms of collagen deficiency differ between intrinsic and extrinsic ageing, the cumulative effects result in dermal atrophy and decrease in the elasticity of the skin (Tzaphlidou 2004).

Wound healing and repair processes decline with age and the inflammatory response, proliferative phase and maturation have all been shown to alter with age (Hardy 1989). Growth factors and their receptors which regulate the wound healing process are also affected by the ageing process (Ashcroft et al 1997). The aged skin is at greater risk of damage and wound dehiscence occurs more frequently in people over the age of 60 (Falanga & Eaglstein 1988).

The main contributing risk factors that can lead to the development of ulceration, infection and gangrene have been identified. However, a number of both local and systemic factors may affect wound healing and facilitate infection (Table 18.3).

Table 18.3 Conditions which may affect healing

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Peripheral arterial disease, venous insufficiency, lymphatic obstruction |

| Endocrine | Diabetes, malnutrition, deficiency syndromes, obesity |

| Immunological | DiGeorge syndrome, hypogammaglobulinaemia, human immunodeficiency virus infection, rheumatoid arthritis and hypersensitivity |

| Immunosuppressive agents | Long-term steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, radiation, cytotoxic drugs |

| Infectious | Cytomegalovirus, infectious mononucleosis, bacterial and fungal agents |

| Haematological | Luekaemia, anaemias, haemophilia, sickle-cell anaemia |

| Musculoskeletal | Deformities, hypermobility |

| Neoplasia | Carcinoma, lymphomas, sarcomas |

| Respiratory | Chronic obstructive airways disease |

| Renal | Chronic nephropathy |

| Traumatic | Burns, foreign bodies, repeated minor trauma, tight hosiery |

| Exogenous factors | Inappropriate dressings, antiseptics, harsh environment, caustics and irritants |

Wound assessment

The process of wound assessment is important for:

• determining the aetiology, extent and severity of the wound and the risks posed to the patient

• determining the health and nutritional status of the patient and their ability to heal normally without complications

• designing and justifying a management plan and documenting the improvement/deterioration accordingly

• classifying the wound for clinical management, audit and research purposes

• providing a complete, concise documentation including wound size, appearance and perfusion as a written record of a pattern of treatment. This needs to be consistent with agreed standards of care and best practice.

The requirement for complete documentation is vital, considering that litigation is an increasing problem. The first and most essential aspect of wound assessment is to carry out a thorough risk assessment of the patient (see holistic assessment) with the wound to determine what action needs to be considered. A relevant medical and drug history should be taken along with the history of the wound. The key aspects of history taking for the at-risk foot are given in Box 18.2.

Wound size

Practice point

In a pivotal study by Oyibo et al (2001), ulcer area significantly predicted the outcome of foot ulcers (p = 0.04).

Digital planimetry

This method has been described as having excellent intra-rater and inter-rater reliability and validity. This involves a computerised programe using two area calculations of the same tracings (Goldman & Salcido 2002). However, this process takes time and is usually reserved for clinical research.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree