AIMS OF ASSESSMENT

Several aims are served by assessment: identification of problems; elicitation of information for case conceptualisation; determination of past and present level of patient functioning; monitoring treatment outcome. An initial aim of assessment is the identification and objectification of presenting problems. Presenting problems can be objectified by defining them in concrete measurable terms, such as ratings of symptoms and behaviours on standardised questionnaires, or through self-monitoring of problem behaviour or symptom frequency using diary measures. Assessment also aims to determine specific goals for treatment, and such goals should present tangible targets for therapeutic change. Two categories of treatment goal are relevant: general outcome goals that are collaboratively generated between patient and therapist (e.g. eliminating panic attacks, being able to eat in public without intense fear) and process-linked goals derived from a conceptualisation of factors maintaining patient problems and which guide the content of treatment (e.g. goals to modify belief in negative automatic thoughts, reduce attentional bias, strengthen new beliefs). Measurement should be used to determine progress in meeting treatment goals, and should be used as a guide to modifying components of treatment in a way that maximises the probability of cognitive-behavioural change. For purposes of formulation and to aid the therapist in determining if treatment is affecting key theoretical variables as intended, several rating scales are presented in the Appendix. These scales reflect the types of process ratings typically constructed or used to assess progress in cognitive therapy. They are also useful as a means of reducing therapist drift in treatment when used as intended on a sessional basis. Measurement, a particular form of assessment, therefore aims to monitor treatment outcome as well as to determine if specific processes involved in the maintenance of disorder are successfully modified.

Measurement

Two categories of measurement most frequently used are standard or global measures, and specific target measures. Standard measures are measures that are developed for particular populations and problems and have good psychometric properties (validity and reliability). Examples of standard measures often used in cognitive therapy are: Beck Anxiety Inventory; Beck Depression Inventory; Beck Hopelessness Scale; Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire; Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale/Social Avoidance and Distress Scale; Maudsley Obsessional-Compulsive Inventory. In contrast, specific target measures are developed for use in individual cases and include measures of panic attack frequency; belief ratings; diary measures, duration of exposure; frequency of checking behaviour, etc.

The Beck scales (Anxiety and Depression Inventories) and specific target measures such as the rating scales presented in this book are typically administered on a sessional basis in cognitive therapy.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The BDI (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock & Erbaugh, 1961), is a 21-item self-report scale measuring severity of depressive symptoms. Each item comprises four statements reflecting gradations in the intensity of depressive symptoms. Respondents are asked to choose the statement that best describes the way they have felt over the past week. Each statement corresponds with a score (0–3) and the overall score is derived from a summation of individual items. The score may be interpreted as follows: 0–9, normal range; 10–15, mild depression; 16–19, mild-moderate depression; 20–29, moderate-severe depression; 30–63, severe depression.

Items 2 and 9 on the BDI should be examined independently since they provide an indication of degree of hopelessness and suicidality (respectively). High scores on these items indicate the need for detailed assessment of suicidal risk, and indicate the need to challenge hopelessness, and reduce suicidal risk in treatment.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The BAI (Beck, Epstein, Brown & Steer, 1988) is a 21-item self-report instrument designed to measure the severity of physiological and cognitive anxiety symptoms (e.g. numbness or tingling; feeling hot; wobbliness in legs; fear of worst happening) over the preceding week including the day of administration. Subject responses to each item are required on a 4-point scale consisting of the points: ‘not at all, mildly, moderately, severely’, corresponding to individual scores of 0–3. Total score is achieved by summating the ratings of individual symptom items.

Hopelessness Scale (HS)

Hopelessness can interfere with engagement in treatment, and the Hopelessness Scale (Beck, Weissman, Lester & Trocler, 1974) is a predictor of suicide intent, and suicide in outpatients. Assessment and treatment of hopelessness when present is therefore crucial. The Hopelessness Scale measures negative appraisals about the future, and consists of 20 items requiring a True/False response. A score of 1 is allocated to each response indicating pessimism concerning the future, and a total score is obtained from a summation of such responses. Interpretation of the total score is as follows: 0–3, no/ minimal hopelessness; 4–8, mild hopelessness; 9–14, moderate hopelessness; 15–20, severe hopelessness.

The Beck scales are published by the Psychological Corporation (contact: The Psychological Corporation, Foots Cray High Street, Sidcup, Kent DA14 4BR, UK).

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The STAI (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg & Jacobs, 1983) measures two anxiety constructs each on a separate subscale: state-anxiety and trait-anxiety. State-anxiety is the intensity of an emotional state of anxiety at a given moment in time and is characterised by tension, apprehension, nervousness, worry and autonomic arousal. Trait-anxiety is a relatively stable individual difference in anxiety-proneness, and as such is conceptualised as a personality characteristic. Individuals high in trait-anxiety are more likely to experience high state-anxiety in threatening situations. Both the state- and trait-anxiety subscales consist of 20 items with a 4-point response scale. The state-anxiety response scale consists of the responses ‘not at all; somewhat; moderately so; very much so’, and asks for responses referring to feelings ‘right now, at this moment’ on items such as ‘I feel calm; I am tense; I feel strained’. Some items are reverse scored.

The trait-anxiety subscale elicits responses on a 4-point scale with the options ‘almost never; sometimes; often; almost always’, and is presented with the instruction to ‘indicate how you generally feel’. Examples of items are: ‘I feel nervous and restless; I feel like a failure; I feel rested.’

The STAI has been used extensively in research; its psychometric properties are well established, and norms are available. (The STAI is published by Consulting Psychologists Press, and the distributor in UK and Ireland is: Oxford Psychologists Press, Lambourne House, 311–321 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 7JH, UK.)

RECOMMENDED ADDITIONAL MEASURES FOR SPECIFIC DISORDERS

In this section measures that are useful in the assessment and treatment of particular anxiety disorders are considered.

Panic disorder and agoraphobia

Agoraphobic Cognitions Questionnaire (ACQ)

The ACQ (Chambless, Caputo, Bright & Gallagher, 1984) is a measure of thoughts (catastrophic misinterpretations) about the negative consequences of anxiety. It consists of 14 items (thoughts) and asks respondents to rate ‘how often each thought occurs when you are nervous’. Responses are required on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (thought never occurs) to 5 (thought always occurs). Items of the ACQ are presented in Table 2.0.

Table 2.0 Items of the Agoraphobic Cognition Questionnaire*

| I am going to throw up |

| I am going to pass out |

| I must have a brain tumour |

| I will have a heart attack |

| I will choke to death |

| I am going to act foolish |

| I am going blind |

| I will not be able to control myself |

| I will hurt someone |

| I am going to have a stroke |

| I am going to go crazy |

| I am going to scream |

| I am going to babble and talk funny |

| I will be paralysed with fear |

* ACQ: Chambless, Caputo, Bright and Gallagher (1984)

A useful modification of the questionnaire incorporates belief rating for each item, i.e. ‘How much do you believe each thought when you are anxious’: (0–100 per cent). The modified version has been developed and used by the Oxford Group (Clark & Salkovskis). The ACQ is an indispensable tool in the assessment and cognitive treatment of panic. Some of the items are also useful in the assessment of other anxiety disorders (e.g. Chambless & Gracely, 1989).

Fear Questionnaire

The Fear Questionnaire (Marks & Mathews, 1979) is a 15-item instrument with the items corresponding to the 15 commonest phobias. Three phobia subscores (agoraphobia; blood-injury phobia; social phobia) can be derived each from the sum of 5 items. Respondents are asked to rate on a 9-point scale ranging from 0 (would not avoid it) to 8 (always avoid it) a range of situations. The situations are listed in Table 2.1.

Marks and Mathews (1979) report test-retest reliabilities (n = 20 phobic patients) over a one-week period for the subscales agoraphobia = 0.89, blood injury = 0.96, social = 0.82, with a total score of 0.82. The scale appears to be sensitive to treatment. In summary the Fear Questionnaire offers a valuable self-report assessment of types of phobic avoidance, and is useful in the assessment and treatment of most anxiety disorders. A copy of the full scale is reproduced in the Marks and Mathews (1979) paper.

Diary measures

Diary records for monitoring the daily frequency and intensity of panic attacks, and for monitoring triggers for panic, provide valuable assessment information and data for gauging treatment effects. These diaries also include columns for noting misinterpretations and responses to misinterpretations for use later in the treatment (see Chapter 5).

Table 2.1 Items of the Fear Questionnaire*

| Agoraphobia 4. Travelling alone by bus or coach 5. Walking alone in busy streets 7. Going into crowded shops 11. Going alone far from home 14. Large open spaces |

| Blood injury phobia 1. Injection or minor surgery 3. Hospital 9. Sight of blood 12. Thought of injury or illness 15. Going to the dentist |

| Social phobia 2. Eating or drinking with other people 6. Being watched or stared at 8. Talking to people in authority 10. Being criticised 13. Speaking or acting to an audience |

* Marks and Matthews (1979)

Note: Numbering represents ordering of items on the original questionnaire

Health anxiety

There are few well-validated self-report instruments relevant to assessment of health anxiety. Existing published measures tend not to be targeted at assessing specific disease convictions or underlying beliefs. Some potentially useful measures are presented here.

Symptom Interpretation Questionnaire (SIQ)

The SIQ (Robbins & Kirmayer, 1991) measures causal attributions for common physical symptoms. A total of 13 somatic symptoms are presented followed by three items addressing different possible causes (physical illness, emotional/stress, and an environmental/normalising cause). For example:

For each possible cause respondents are required to indicate its appraised likelihood on a 4-point scale; ‘not at all; somewhat; quite a bit; or a great deal’. The questionnaire is scored by summating the scores on items belonging to each category of attribution. A copy of the questionnaire is produced in the Robbins and Kirmayer (1991) article.

Private body consciousness

Private body consciousness (Miller, Murphy & Buss, 1981) is a subcategory of body consciousness, the tendency to focus attention on one’s body. The private body consciousness subscale consists of 5 items assessing awareness of internal bodily sensations in non-affective states. Items include: ‘I can often feel my heart beating; I know immediately when my mouth or throat get dry.’ Responses to these items are made on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘extremely uncharacteristic’ (0) to ‘extremely characteristic’ (4). Total score is derived from summating individual item scores. Miller et al. (1981) report test–retest reliabilities over a two month period for the subscale of 0.69.

Illness Attitude Scale (IAS)

The IAS (Kellner, 1986) is a 29-item self-report measure of: worry about health; death; bodily preoccupation; illness behaviour; concern about pain; and hypochondriacal beliefs. The scale can be useful for highlighting areas that need to be covered in treatment. The scale measures nine areas with three questions tapping each one:

The Health Anxiety Questionnaire (HAQ)

The HAQ (Lucock & Morley, 1996) is a 21-item measure of symptoms of health anxiety based on items of the IAS (Kellner, 1986). Responses are made on a 4-point scale. Four clusters of items were obtained in the analysis reported by Lucock and Morley (1996): fear of illness and death; interference with life; reassurance-seeking behaviours; health worry and preoccupation. Factor analysis of items in which four factors were extracted with eigenvalues greater than 1 revealed that health worry and preoccupation, and interference with life loaded on the same factor, the fourth factor appeared to be largely redundant. Test–retest correlations over a 4–7-week period for the total scale score was 0.53 for medical outpatients (n = 46) and 0.95 for clinical psychology outpatients (n = 17) presenting with anxiety problems. The scale distinguishes patients with a diagnosis of hypochondriasis (n = 23) from a group (n = 26) of other anxiety disorders (GAD, panic, social phobia). Correlation between HAQ and the BDI for 41 clinical psychology patients (with diagnoses of panic, social phobia, GAD, hypochondriasis, or mixed diagnoses) is reported at 0.42. Further evaluations are required of the properties of the scale but it appears promising for delineating areas for treatment.

Social phobia

Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE), and Social Avoidance and Distress (SAD) scales

These two scales were developed to measure the cognitive (FNE), and affective/behavioural (SAD) components of social anxiety (Watson & Friend, 1969). The instruments have been widely used in social phobia treatment research, although limitations of the instruments exist. More specifically, some items are reversed which can cause confusion, and the response format is ‘True/False’ which diminishes the potential sensitivity of the scales. The FNE scale consists of 30 items, while the SAD scale consists of 28 items. Example items from the scales are:

| FNE: | I worry that others will think I am not worthwhile. I am afraid that people will find fault with me. |

| SAD: | I often find social occasions upsetting. I tend to withdraw from people. |

Social Cognitions Questionnaire (SCQ)

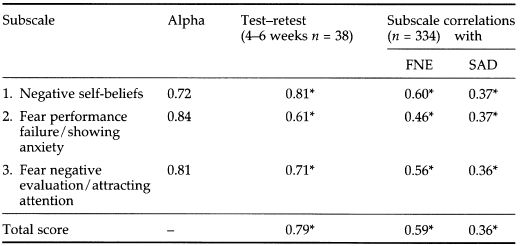

The SCQ (Wells, Stopa & Clark, unpublished) was developed to assess a wide range of negative self-appraisals, fear of negative evaluation by others, and negative beliefs in social phobia. Responses are required on a 0–100 scale of belief ranging from 0 (I do not believe this thought) to 100 (I am completely convinced this thought is true). Original items for the scale were derived from clinical interviews with social phobics. While the scale is used to derive an overall score clinically, factor analysis (with non-anxious subjects) suggest the scale may have three dimensions of: (1) negative self-beliefs; (2) fear of performance failure and showing anxiety; (3) fear of negative evaluation and attracting attention. However, some items overlap and subscale intercorrelations are high. Psychometric properties of the SCQ are presented in Table 2.2. Further research is needed to explore the psychometric properties of the questionnaire with patient groups. However, the scale provides a useful clinical tool for identifying and monitoring thoughts and beliefs. The scale appears to be sensitive to treatment effects.

Table 2.2 Psychometric properties of the SCQ (non-anxious subjects)

Source: Stopa (1995)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree