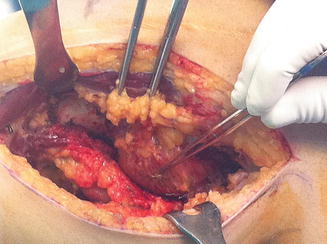

Fig. 10.1

Hemophilic pseudotumor opened after surgical resection

10.4 Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Patients present with painless palpable masses or with painful crises due to episodic acute bleeding into the tumor. Most of the morbidity from pseudotumors is due to their compressive effect on surrounding structures. Depending on the area involved, the symptoms include palpable masses, numbness, weakness, and neuralgia. Complications occur because progressive enlargement occurs, leading to compression of neighboring vital structures, destruction of soft tissues, and bone erosion, which may produce neurovascular complications. Ultimately there may be perforation through the skin or into adjacent organs, abscess and fistula formation, fatal hemorrhage, pathologic fractures due to bone destruction, and compartment syndromes due to vascular compromise and joint contractures [5].

In X-rays, lesions in proximity to long bones, there is a large soft-tissue mass with areas of adjacent bone destruction. The bone loss may be extensive, involving diaphysis and metaphysis and even destroying adjacent bones by crossing the joints. Periosteal elevation with new bone formation can be seen at the periphery of these lesions. Calcification and ossification within the soft-tissue mass are frequently noted [2, 12]. In pelvic pseudotumors, the radiographic picture differs from those previously described in that the soft-tissue mass, and the extent of pelvic bone destruction, most of which occurs in the iliac wing, may be difficult to appreciate on plain X-ray films. Periosteal elevation and calcification within these lesions are much less common. An intravenous pyelogram should be performed if there is any concern about displacement of the ureters.

CT scans define the attenuation value of the tumor and thus help to differentiate it from other masses. It clearly delineates the size and extent of the tumor and compression of the adjacent skeleton, tissues, and organs. CT may prove useful in determining the origin of the pseudotumor and help follow its course. CT scans have been proven to be particularly efficient in the detection of daughter cysts, deep-seated cysts, and tumor extension into adjacent tissues, information that is useful in planning surgery [13].

Ultrasonography is ineffective for the detection of bony changes. It can be used after surgery to monitor for recurrence of pseudotumors in soft tissues. It has also been suggested as a low-cost alternative to monitor the progress of an existing lesion before obtaining a CT scan prior to repeated surgery [13].

MRI has been shown to be superior to other modalities for the imaging of soft tissues. MRI is sensitive for the detection of pseudotumors and can provide useful information for decisions regarding therapy and may be used to follow the response of a tumor to treatment. The appearance on MRI seems nonspecific with a similar appearance in tumors and abscesses, but invariably there are heterogeneous low and high signal intensity areas on both pulse sequences, reflecting the presence of blood products in various stages of evolution [14, 15].

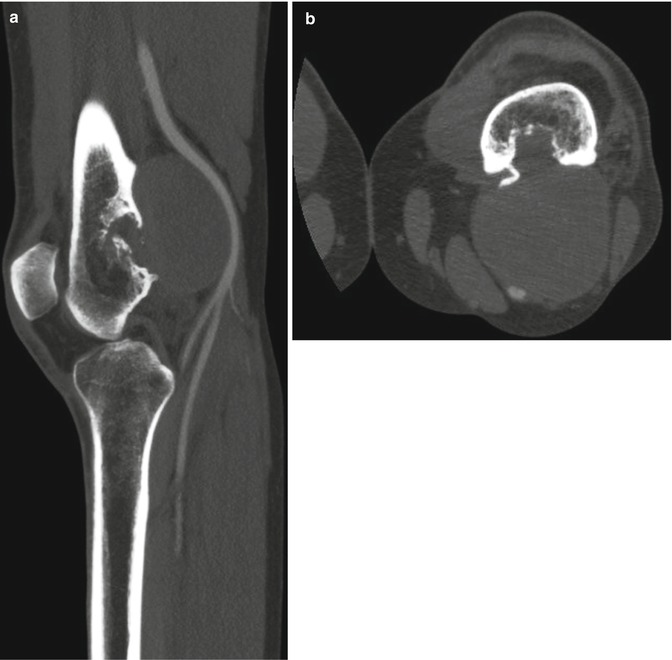

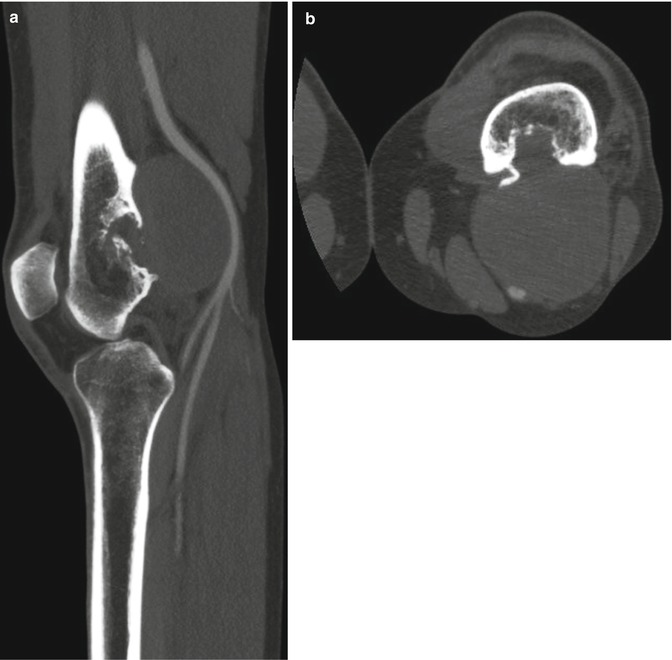

CT and MRI scans are considerably more useful than plain X-rays and may be sufficient to evaluate displacement of the large vessels (Fig. 10.2). Imaging characteristics of pseudotumors are rather nonspecific, but given a history of hemophilia, radiologists must be aware of these to avoid misinterpretation.

Fig. 10.2

CT of a hemophilic pseudotumor and its relationship with the popliteal artery: (a) sagittal view; (b) axial view

10.5 Treatment

The management of the patient with a hemophilic pseudotumor is complex and carries a high rate of potential complications. It is important that they are diagnosed early, and prevention of muscular hematomas is key to reducing their incidence. Muscle hematomas should be avoided by primary prophylaxis, and if a muscle hematoma does develop, it must be treated hematologically on a long-term basis until total shrinkage and disappearance of the hematoma have occurred [16].

Hemophilic pseudotumor are uncommon; therefore, there is no consensus about specific management. There are different treatment options (surgical removal and exeresis, and filling of the dead cavity, percutaneous management, embolization, radiation), and it would be necessary to individualize therapy. With the increasing availability of factor replacement, surgical removal is feasible.

Preoperative biopsy or aspiration of the fluid within the cysts for either diagnostic or therapeutic purposes is contraindicated. The cystic contents are too thick to permit successful aspiration, and there is a high risk of relapse, infection, or the development of a persistent fistula [10].

Conservative treatment includes long-term factor replacement and immobilization of the affected area. Distal pseudotumors in children respond well to conservative approach. However, it fails to prevent progression of the lesion especially in proximal lesions, and recurrence and progression is the rule [6].

10.5.1 Surgical Removal

Surgical removal is the treatment of choice when it can be carried out in major hemophilia centers and careful preoperative planning can be done, because these procedures are fraught with difficulty and carry a high complication rate. Surgery is the most effective treatment and should be performed upon diagnosis when the pseudotumor is still small and relatively easily resected. Lesions in proximity to the long bones and lesions of the pelvis should be managed in different ways, and in fact, the surgical approach to these lesions must be individualized.

When the lesion is in the proximity of long bones, the aim should be complete resection of the lesion, stabilization and bone grafting if required, hemostasis, and closure of the dead space. Implantation of a tumoral prosthesis for reconstruction of massive juxta-articular bone lesions can be necessary; although the authors have no experience with this type of reconstruction in hemophilic pseudotumors, it is routinely used for reconstruction after resection of bone sarcomas, and primary arthroplasty in hemophilic patients is also a common procedure in our hospital. The incision has to be planned to allow access to the neurovascular structures, removal of the lesion, and fixation of bone if necessary. Neurovascular structures should be identified and retracted prior to remove the blood cyst (Fig. 10.3). It usually is within a muscle mass and during dissection tries to stay on the fibrous capsule and then as much muscle as possible should be preserved. The portion of muscle wall that is directly adjacent to the bone can be removed easily with cautery dissection and curettes. Bleeding from the bone or other surfaces can be controlled during surgery by the use of fibrin glue. Bone fixation is an important part of the procedure when necessary; intramedullary nailing has been most often used to stabilize diaphyseal or proximal femur fractures, but when the lesions are around the knee, fixation with periarticular plates can be more useful. Reconstruction of the bone defect after removing the pseudotumor can be done with bone graft, bone substitutes, or bone cement (Fig. 10.4), especially in metaphyseal or epiphyseal defects that involve mechanical risk. At this point, meticulous hemostasis should be obtained. Coverage of the remaining bone should then be addressed, using a muscle flap if necessary. A suction drain is always used and a bulky pressure dressing applied. The use of plaster and the weight-bearing status must be calculated for the individual patient, depending upon the lesion itself and the extent of arthropathy in other joints. Nonunion of pathological fractures has not been a problem, because large denuded bone surfaces result in abundant new bone formation.